✨ Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a newsletter dedicated to celebrating Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every Monday, you’ll be receiving a tasty mix of food history, stories, and recipes straight in your inbox. This week, Eamonn Donnelly takes us through a deep-dive on tomato shio ramen (which happens to be vegan!), exploring everything from the broth to the tare. This newsletter is 100% reader-funded; if you’re enjoying the read in your inbox each week, then please subscribe below — each paid subscription supports the writing and research that goes into the newsletter, pays guest writers, and gives you access to all content and recipes. Thank you for being here and enjoy this week’s newsletter! - Pamelia✨

Tomato Shio Ramen

by Eamonn Donnelly / @eamonndd / u/_reamen_

I am a ramen head.

By my definition, that means I obsess, a little, over what makes ramen good. Ask me where you should go to eat ramen, and I can definitely point you to which shop in my part of the world makes its noodles in-house. I am a home cook, but I have learned first-hand just how much work goes into a proper bowl. My passion for making ramen stems from the same forces that drive my work as an art director, graphic designer, and musician: creativity and curiosity. They drew me into the kitchen, and something about the pursuit of perfection, the details, and possible combinations that go into a bowl of ramen kept me coming back.

What continues to inspire me is the path to good vegan ramen. Most ramen that you might encounter features chicken, pork, or seafood; these types of ramen, such as tori paitan or tonkotsu, have served and satisfied ramen lovers for decades. Vegan ramen seems to be less explored—at least in the English-speaking world—and I find it far more interesting. According to the noted American ramen chef-restaurateur Ivan Orkin, ramen is a “maverick cuisine.” Knowing that this genre of food has a habit of breaking its own rules freed me up to research how to incorporate new ingredients and techniques while staying true to the dish’s humble origins.

While there are endless ramen variations, almost every bowl has the following five elements: Broth, Tare, Noodles, Aroma oil, and Toppings. I’ll delve into each component of my vegan ramen below.

Broth

Most broths for ramen can be identified as either a chintan (clear soup) or paitan (opaque soup). How you cook the broth determines which kind you end up with: generally, soup cooked at a low-simmering temperature will be clearer, while soups cooked at a rolling boil will cause the fats to emulsify, clouding the final broth. The broth is arguably the most time-intensive part of making a traditional bowl of ramen. With a pork-based tonkotsu broth, it can take at least 6 to 12 hours to convert the collagen in pork bones to gelatine and for it to emulsify with the broth to produce the tonkotsu’s characteristically creamy, silky consistency.

A vegan ramen broth does not need nearly as much time, as vegetables break down faster in boiling water compared to meat-based ingredients. However, the lack of collagen and fat compared to animal protein means that it requires some creativity on the part of the cook. The fun for me in making vegan ramen is also seeking out alternate sources and methods that add umami and flavor.

Dashi, a simple broth derived from relatively few ingredients, is not just essential to making good ramen, but to Japanese cooking in general. Traditionally made by soaking and heating kombu and dried bonito flakes (smoked and dried fish) in water briefly, one can extract their peak flavour and produce a mild broth that is backed by an intense sensation of umami. In shojin ryori, or Japanese Buddhist cuisine, a vegetarian dashi is made by substituting dried bonito flakes with dried shiitake mushrooms. The mushrooms are naturally abundant in amino acids like glutamate and guanylate, providing a synergistic effect when combined with the glutamate from kombu where the perceived level of umami is many times higher than just using these ingredients on their own.

I also learned about tomato water, a wonderfully clear product that one could obtain by blending fresh tomatoes to a puree and passing the liquid through a cheesecloth. The tomato water is naturally umami and using it in place of water to make a tomato dashi seemed the perfect way to add an additional layer of depth.

To get around the lack of collagen and fat in vegetables, there are several ways one can enrich a vegan broth and add a sleeker texture: add a plant-based source of fat, such as oat milk or cashew milk; blend all of the soup’s ingredients and strain out the solids; and incorporating avocado puree or aquafaba. For this bowl, I simply added oat milk to my tomato dashi. I have previously experimented with soy milk; however, in my experience, commercial soy milk is much thinner and does not have the same level of fat and starches which enhance the mouthfeel of the soup.

Tare

Tare is a rich, potent sauce or paste that ultimately classifies the style of your bowl. When you see shoyu ramen on a shop menu, that means that it is flavored with a soy sauce tare, for example. The tare is meant to be intensely seasoned, complex, and umami-laden. Only a small amount is required to make your broth shine. For this bowl, I made a shio, or salt-based, tare by seasoning a kombu and dried shiitake mushroom dashi with salt, vinegar, and shiro shoyu (white soy sauce). This tare is one of the examples where the “lines” of ramen get a little blurred. Technically, maybe this tare should be a shoyu. Shiro shoyu is primarily wheat-based, fermented for a considerably shorter time than traditional soy sauces with a higher soy-to-wheat ratio. This gives shiro shoyu a sweeter, more wheat-forward flavor as well as its pale color. In a tare, it brings more complexity and salinity without having to add more salt.

Noodles

The noodles are truly what sets ramen apart from other noodle dishes. The alkaline salts used to make the noodles give them their unique chewy quality, slightly yellow color, and they help the noodles maintain their shape in hot broth. (I’ve seen some people demean attempts at vegan ramen for trying to interpret or re-create what is “meat-based” fare, but… Sorry! It’s the noodles that define the dish.)

I won’t sugarcoat it. Making ramen noodles from scratch can be disheartening, especially if you’re a novice. They are the most complicated component of the dish yet they seem so simple: Mix water, wheat flour, kansui (alkaline salts), and sea salt to form a dough. Knead the dough, flatten it into a sheet, and cut it. Sounds pretty doable, right? But you come to realize pretty quickly that noodle-making requires precision, patience, awareness of a long list of details that can impact the final product, and, in the extreme, equipment that can cost as much as a car. There’s a reason some ramen chefs spend their lives striving to achieve perfection.

As much as I have come to love making noodles, my advice is to save it for another day. If you are able to source fresh, store-bought noodles like Sun Noodles at a nearby Asian grocery, awesome! You’ll be saving yourself a lot of time and headache. If you get into the habit of making ramen, work on some of the other components like the broth or tare, then tackle homemade noodles when you’re feeling more confident. In the meantime, I would highly recommend you consult a free ebook from Chicago-based ramen chef Mike Satinover (a k a Ramen Lord). He does a fantastic job diving into the science behind ramen noodles, and has time-tested techniques for how they can feasibly be made at home.

Aroma Oil

The aroma oil is the underdog of your bowl. Any ramen, no matter how delicious its tare or toppings, is duller without it. That’s because it entices you before your first slurp. As the aroma oil mingles with the hot broth, its fat molecules are released into the air, setting the expectation for the feast of flavors to come. It is a particularly important component for vegan ramen, where you can’t rely on extracting fat from animal bones into the soup. The fat introduced from the aroma oil is crucial to the overall experience, and it even helps keep your soup hot. The aroma oil that I use in this bowl of ramen is fried garlic and shallot oil. I prefer the low-and-slow approach here and begin the frying from cold oil. The advantages are manifold: you extract more aroma and flavor from the ingredients without the risk of burning; and there will be less violent splatters everywhere. While the oil may not smell like much after the initial cook, the toasty, garlicky-shallot aroma gets stronger once it is mixed into a hot broth. (The strained bits of garlic and shallot also make for an awesome roasty, crunchy ramen topping.)

Toppings

Toppings are versatile and often visually appealing — and therefore an easy component to get creative with. They can bring more protein into a bowl, enhance or even change its flavor, and add contrasting textures. I roast tomatoes, specifically Roma tomatoes for their flavor and for being perfectly bite-size. The rehydrated shiitake mushrooms from making the dashi component do not go to waste; I marinate them in soy sauce and water overnight and warm them up in a pan the next day.

Putting the ramen together

Once all the components are made, the only thing left to do is to assemble the ramen. An oft-overlooked step is the heating of serving bowls prior to serving; I highly recommend this. It may seem trivial, but a warm bowl keeps your soup closer to the ideal temperature it’s meant to be served at. A cold or room-temp bowl will absorb a lot of the soup’s heat, leaving something that is more lukewarm than hot. All those umami compounds and flavors you worked hard to develop are not at their peak in a lukewarm environment.

Eating ramen is a lesson on living in the moment. Your senses are fully engaged by the temperatures, flavours, and textures, and the task at hand is to savour it all during the small window when the bowl before you is at its peak. Miss it, and the noodles will become mushy, or the broth will cool, or your perception of its umami will be diminished. The recipe in the accompanying newsletter represents a suitable summation of just how transcendent and unique vegan ramen can be.

Eamonn Donnelly is a full-time art director/graphic designer and a part-time musician. He lives in the Washington D.C. suburbs.

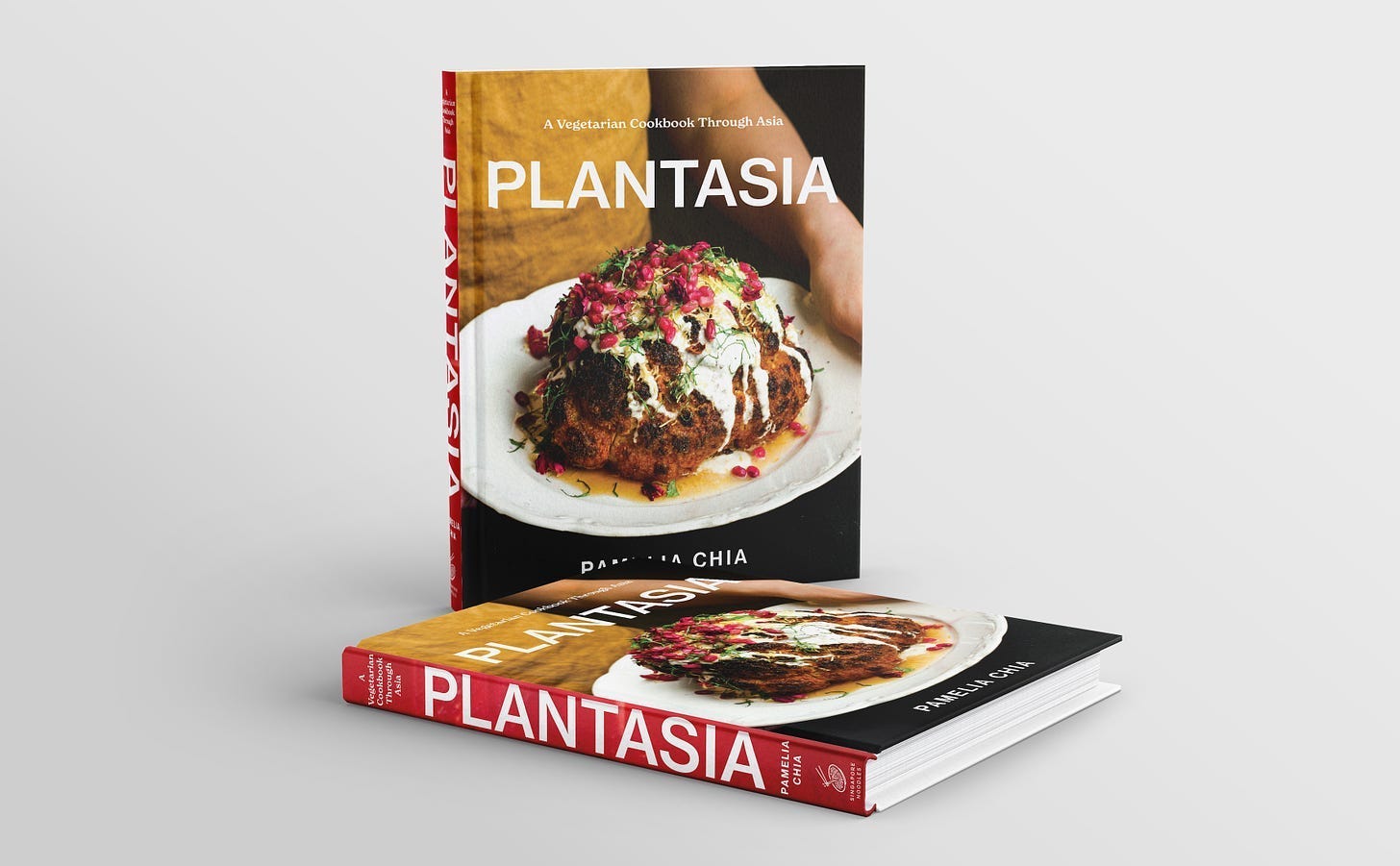

🥦 My second cookbook Plantasia: A Vegetarian Cookbook Through Asia leverages Asia’s techniques and flavour combinations to expand your repertoire of vegetable dishes deliciously beyond Western-style salads. Pick up your copy here or find a stockist near you. It is mostly vegan (or easily veganised), with plenty of allium-free options.