Olá from Portugal! I’m currently on holiday, so I’ve invited culinary teacher and pastry chef Yeo Min to guest-write this week’s newsletter. Before we get to the deep-dive, a quick announcement in case you missed it: if you are a paid subscriber or if you have preordered Plantasia, join us for a virtual cookalong on 24 September (Sunday) where we will be making mushroom ramen from the book!

Yeo Min specialises in Chinese pastries and is releasing a cookbook called Chinese Pastry School later this year. In today’s newsletter, she is sharing all about a traditional pastry from her cookbook: heong piah 香饼. The pastry literally means ‘fragrant pastry’ in Hokkien and the first time I ever had it was when my sister-in-law brought some home from Malaysia. Each biscuit was filled with oozing, fragrant malted caramel and I fell in love with them. When I learnt that heong piah features in Yeo Min’s cookbook, I invited her to share about it because it is a pastry that not many know about. Now over to Yeo Min!

Heong Piah

By Yeo Min (Singapore)

I can’t remember the first time I had heong piah. All I remember is that the ones that I tasted in my childhood were bought from Malaysia. I got to rediscover heong piah as an adult when I first started going out with my partner, Gangyi. His parents buy this pastry on a regular basis so it’s a snack they almost always have at home. Gangyi brought me to the small kopitiam bakery in Bugis that his family gets them from, and taught me to reheat my heong piah just before eating. I was completely blown away - the pastry concealed a melty, gooey centre made using maltose, shallot oil and toasted sesame seeds. Unlike other types of Chinese pastry such as lao po bing 老婆饼 (wife biscuits) that have a soft pastry and Teochew mooncakes that are crispy, heong piah is known for its crunchy pastry.

This is owed to the way they are traditionally prepared. As tandoor-style ovens were the first ovens to arrive in Ancient China from India, heong piah was traditionally baked in cylindrical clay ovens. In Malaysia, bakers use coconut husks to fuel the fire instead of burning coals. The intense heat trapped within the oven is what contributes to the pastry’s overall crunchiness. Because bakers stick the pastries onto the sides of the oven to bake, they develop a thicker crust on one end. Their resemblance to a horse hoof is what earns them the alternative name ‘horse hoof biscuit’ (beh teh saw in Hokkien or ma ti su in Mandarin 马蹄酥).

While the original heong piah found in Fujian province features a leavened dough and a sugar paste, the version that you will find in Singapore and Malaysia is made with a laminated puff pastry wrapped around a sweet molten filling. Today, very few bakeries in Singapore make heong piah. Apart from the bakery that Gangyi and I visited in Bugis, Tan Hock Seng, a 90-year-old Chinese bakery in Chinatown, used to sell them too before it closed in 2022.

The closure of traditional Chinese pastry shops like Tan Hock Seng was what prompted me to learn more about the making of traditional pastries. Heong piah turned out to be an especially tricky one to master. The difficulty lies in achieving a fragrant, gooey filling that does not explode through the pastry during the baking process.

The goo

Maltose is what lends heong piah its unique gooey centre. It is one of the earliest man-made sweeteners, made by breaking down the starches in cooked glutinous rice and wheat grass to form a sticky syrup. Compared to other sugars or syrups, it is viscous and less sweet. For this reason, it is perfect in heong piah, allowing for a thick, gooey filling that is not too sweet. (Because of its neutral flavour and low level of sweetness, it is also used to add a lacquered, shiny appearance to savoury foods such as char siu or roast duck.)

All you need are wheat berries and glutinous rice. In most Western countries, the former is not difficult to procure wheat berries as people tend to eat sprouted wheat as a health food or use it in their sourdough. In Singapore, you can purchase organic sprouting-grade wheat berries on Shopee. (I tried making heong piah once with a bag of $2 wheat berries from Sheng Siong - these were husked and molded instead of sprouting!)

While you can find maltose in supermarkets and baking specialty stores, the commerical variety cannot compare to the fragrance of a homemade tub of maltose. According to this fantastic article on the making of maltose syrup, homemade maltose retains complex compounds that give it its unique flavour: “malty and delicate, a bit like barley malt crossed with brown rice syrup but less sweet”.

Shallot oil

Shallot oil and roasted sesame seeds are what put the “heong” (fragrant) in heong piah. To the uninitiated, using shallots in sweets might sound odd. However, this is common in a range of sweets that are beloved in Singapore such as orh nee and ang ku kueh. Even though shallots are typically associated with savoury dishes in the West, they are used as a dessert ingredient for the Chinese community as they turn sweet and mellow when cooked. While ready-made fried shallots can be easily bought from the supermarket, shallot oil can only be obtained by frying shallots at home.

Frying shallots is an underrated skill, but do it right and you will have superbly fragrant oil and crispy shallots that are evenly fried. To achieve this, it all starts with slicing your shallots in the right direction. While helping out at my teacher Pang Nyuk Yoon’s cooking demonstrations, I learnt that the way you slice shallots for shallot oil matters. When you slice them lengthwise, you get even slivers that will fry evenly. Slice them crosswise into rings, however, and you will get 3 to 4 different sizes of shallot slices. This means that the smallest shallot rings will burn before the outer rings have a chance to cook through.

Even the frying the shallots takes technique. The best thing to do is to cover the shallots with room temperature oil and cook them on low-medium heat. This thoroughly infuses the oil with the flavour of the shallots and allows the oil to gradually push the water out from the allliums. When they turn translucent, turn the heat up and fry until the shallots become golden brown. The heat has to be high towards the end to fully extract the fragrance from the shallots. Once fried, the shallots and oil are cooled separating before combined for storage and maximum flavour extraction.

Toasted sesame

The second component that makes up the heong piah filling’s characteristic fragrance is toasted sesame seeds. Toasting sesame seeds is one of those techniques you never really get to learn, because it sounds so simple and straightforward… but I’ve learnt that there is a trick to get evenly toasted sesame seeds without accidentally burning them. What you do is rinse the sesame seeds and cook them covered on medium-low heat first. This steams the seeds, bringing their temperature up to 100ºC. When most of the water has evaporated, remove the lid and lower the heat. Stir the seeds constantly to help them colour and toast evenly. They are done when the seeds are puffed up, fragrant and dry.

Pastry that does not explode

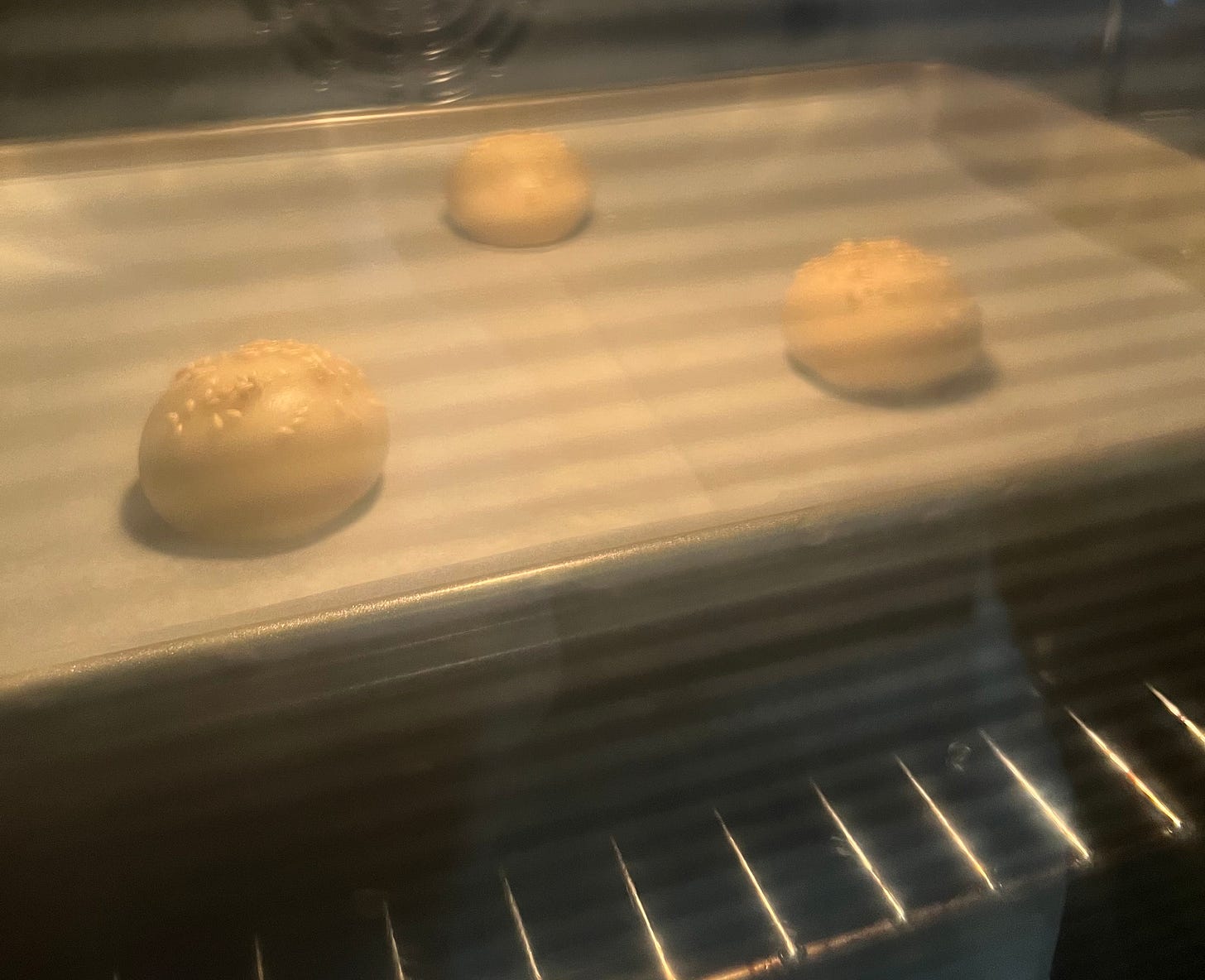

Heong piah’s dough is a laminated one, which means it’s made by stacking a water dough and an oil dough together to create layers. This is tedious to make but not difficult. Instead, the challenge of this pastry comes from ensuring that the pastries don’t explode during the baking process (as the maltose filling turns molten and lava-like when heated, heong piah is extremely susceptible to exploding while in the oven).

Some recipes have suggested wrapping the filling in two layers of pastry as a safeguard from any leakage, but this results in a thick pastry skin with a disproportionately small amount of filling. My workaround is to:

Thicken the filling with some gaofen, or cooked glutinous rice flour. Cooked glutinous flour is simply toasted glutinous rice flour that is commonly used in Chinese pastries as a binder. It is more commonly used for the filling of mooncakes, but I noticed that my teacher, Chef Pang, thickened the malt filling of her heong piah ever so slightly with cooked starch. The added viscosity went a long way in preventing the filling from exploding or leaking out of the pastry. You can make gaofen yourself or purchase it from Asian baking stores, such as Phoon Huat in Singapore.

Set the bottom of the pastry quickly. This effectively forms a seal on the seam of the pastry, thus preventing fillings from leaking. Most home bakers use convection ovens where bottom heat is not particularly strong, but you can imitate the strong heat of the walls of a tandoor oven by using a preheated pizza stone or a stack of baking trays.

While it definitely is a lot of work to make a pastry like heong piah from scratch, I believe that learning to do so or even understanding a sliver of the process allows us to recognise the true value of these pastries. There’s a good reason why people are willing to pay for a macaron despite there being tons of recipes available online — and that is because we know just how finicky they are to make.

I hope that by more people stepping up to share more about the craft and stirring up curiosity in others to learn more, our heritage pastry shops will continue to flourish for decades to come. You’ll find the recipe and steps to make this treat in a separate newsletter 🤓

Where is this Kopitiam in Bugis!! I am so deprived after the close of Tan Hock Seng…

Fascinating! I applaud your dedication to exploring these culinary riches.