Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every week, you’ll be receiving historical tidbits, personal stories, and recipes delivered straight to your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. My cookbooks Wet Market to Table and Plantasia are available for purchase here and here respectively.

Today's deep-dive on steamed taro cake is inspired by a request from one of our paid subscribers. If you're curious about pumpkin kueh, a close cousin to this savory cake, click here to read more. If you're a paid subscriber and have a topic you'd like to suggest, feel free to reach out! Thank you for being here, and enjoy this week’s post. ✨

STEAMED TARO CAKE / ORH KUEH 芋粿 / WU TAO GOU 芋头糕

Orh kueh 芋粿 — ”taro kueh” or “yam cake” in Teochew — is a savoury steamed cake built around taro, a crop prized across southern China for its resilience in poor soils and its nutty, yielding tenderness when cooked. In the coastal Chaoshan region, where sandy land made rice cultivation difficult, taro is not just a critical staple but a symbol of survival. The tuber found its way into everyday dishes — mashed into the rich dessert orh nee 芋泥, cooked with rice in orh png 芋饭, and folded into orh kueh 芋粿. Fields of taro, with their spreading roots and flourishing shoots, came to symbolize deep family ties, abundance, and perserverance, and celebrated in Teochew poetry and folk sayings.

In traditional Teochew kitchens, orh kueh was a dish of thrift and bounty at once: rough chunks of taro folded into a simple rice slurry, and steamed to a dense yet yielding mass. A fistful of dried shrimp and mushrooms — whatever the pantry could spare — sufficed to turn the humble steamed cakes into food fit for both altar and feast. These early taro cakes were stark and unfussy, designed for working people who needed something hearty, durable, and sustaining.

It was only later, with the flourishing of dim sum culture in the 19th- and early 20th-century Cantonese cities, that taro cake — wu tao gou 芋头糕 in Cantonese — was refined into something with finer textures and a lighter touch. Here, the taro is cut into slender slivers, barely held together by a thin, silken batter. The goal is to showcase the taro itself: when you cut into the cake, you’re eating mostly taro, not batter.

Compared to the classic Cantonese version, the version of taro cake more commonly encountered in Singapore is decidedly more rustic. The batter here is more than just a binding agent and is part of the experience, with its slightly chewy, tender, and creamy texture. Studded throughout the batter is taro cubes, not slivers, so that you have distinct bites of velvety root punctuating the smooth rice flour batter.

THE “LIAO” 料

The add-ins, or "liao" 料, are integral to the soul of steamed taro cakes, transforming a simple, austere kueh into something rich and flavourful. Often, the generosity in the addition of these is what distinguishes homemade versions from store-bought ones. Here are some common add-in ingredients and tips on how to prepare them for use:

Dried shrimp (虾米 / hae bee): Soaked in room temperature water briefly, then roughly chopped. Soaking liquid should be saved for later use.

Dried shiitake mushrooms (干香菇 / gon heong gu): Soaked in boiling water until tender, stems snipped off, then caps are finely diced. Soaking liquid should be saved for later use.

Dried scallops (瑶柱 / yao ju): A more luxurious addition, more common in Cantonese versions. Soaked, then torn into fine shreds. Soaking liquid should be saved for later use.

Minced pork: For richer, meatier versions. More commonly found in orh kueh than wu tao gou.

Preserved radish (菜脯 / cai poh): Available in both salty and sweet varieties, preserved radish adds a salty-sweet burst of flavor in every bite. Finely minced cai poh should be quickly rinsed to remove excess salt, then drained before use.

Chinese sausage (腊肠 / lap cheong): Typically covered in a thin, waxy outer layer to preserve the sausage during storage. While not harmful, this layer can be tough and chewy, and should be removed before eating. To do so, lightly score the lap cheong along its length, then soak it in boiling water for about 10 seconds. Once softened, use your fingers to peel off the waxy layer before dicing or mincing the sausage.

Garlic and red onion: Finely chop.

In my taro cake, I use a blend of dried shrimp, dried mushrooms, and Chinese sausage, all finely diced; as well as finely chopped garlic and red onion. This allows the cubes of taro to take centre stage texturally, with the other ingredients playing a supporting role, enhancing the flavour of the kueh in the backdrop.

FRYING THE TARO

When the taro is cut into cubes instead of slivers, precooking before mixing it into the batter becomes essential. The goal is to cook the taro just until tender — when a fork is inserted into a cube, it should hold its shape without crumbling. The final steaming will complete the cooking process gently. Here are the reasons for precooking the taro:

Ensures even cooking: Steaming the kueh doesn’t always guarantee that the taro cubes inside will cook evenly. By precooking, you ensure that the taro cubes are already tender before they’re mixed into the batter.

Enhances flavour: While some cooks choose to steam the taro cubes, I prefer to fry them with the add-ins, salt, white pepper, and five-spice. This gives the taro a flavour headstart. At this stage, I also add the soaking liquid from the dried shrimp and shiitake mushrooms, allowing the taro to soak up all that savoury goodness.

Controls moisture for consistent batter: Raw taro releases moisture as it cooks, which can affect the batter’s consistency. Precooking helps maintain a predictable texture for the batter, preventing a soggy or watery kueh.

THE BATTER

The batter is the glue that holds everything together, defining the texture and bite of the kueh. It is made of:

Rice flour: The main structural component, giving the kueh its firm yet tender body.

Wheat starch, tapioca starch, or cornstarch: These add a slight chewiness and bouncy mouthfeel (that characteristic QQ texture). Wheat starch is the most commonly used, but tapioca starch or cornstarch are passable alternatives.

Water or stock: Hydrates the flours into a batter. The amount of liquid added to the flour determines the final texture of the kueh. It’s a fine balancing act: more liquid increase the kueh’s tenderness, but too much water results in a mushy kueh that is tricky to slice. I use store-bought chicken stock instead of water for depth of flavour.

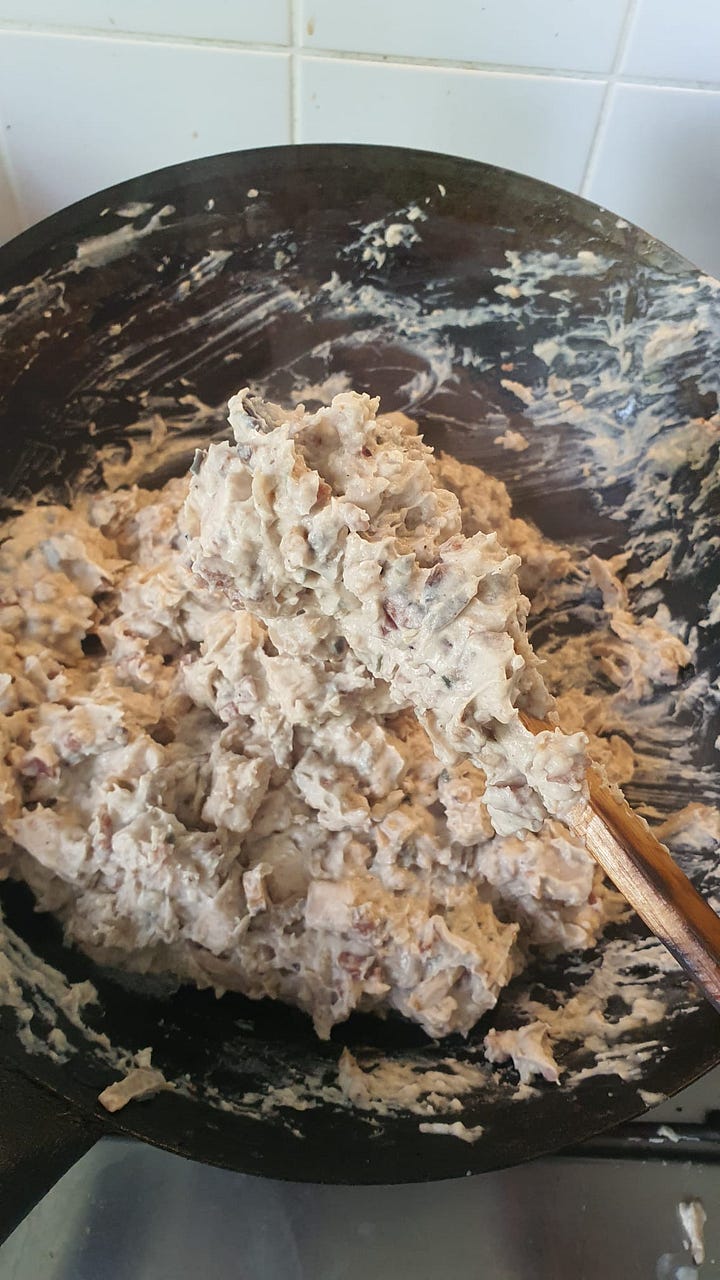

For orh kueh, the batter is cooked with the taro and add-ins until it thickens to a paste-like consistency before steaming. This step is crucial for evenly suspending the taro cubes and other ingredients throughout the kueh, preventing them from floating to the top, and ensuring the kueh holds together beautifully.

Enjoying your taro cake

1. As is.

Traditionally, taro cake was served as is, warm or at room temperature, to highlight the soft creamy texture and the savoury flavours of the kueh.

2. Pan-fried.

While taro cake made with a good proportion of liquid to flours is delicious as is, without becoming dense when cooked, some cooks might want to refresh slices of it by pan-frying. This not only crisps up the outside to contrast the creamy inside, but also browns the surface of the kueh to deepen the flavours further. At dim sum parlours, pan-fried wu tao gou is the default expectation — not just a treatment for leftovers. See photos of pan-fried pumpkin kueh here.

3. With toppings

Traditional orh kueh or wu tou gou has few or no toppings — the flavour is inside the cake, not on top. However, in Singapore, garnishing kueh with colorful and texturally satisfying toppings is a common practice. Here are some options:

Fried shallots

Chopped spring onions or coriander leaves

Extra fried dried shrimp

Preserved radish (cai poh)

Sliced or minced red chilli

Crushed peanuts

Toasted sesame seeds

Along with the toppings, in Singapore, orh kueh is typically served with some form of chili condiment — ranging from sambal belacan and dried shrimp sambal to sriracha.

4. Stir-fried with egg.

Hawker stalls needed fast, affordable, and hearty meals to cater to locals who preferred whole dishes over small dim sum snacks. Since local palates loved wok hei, bold flavors, and strong sauces, inventive Teochew hawkers began cutting the savory kueh into small chunks and stir-frying it with eggs, preserved radish, and sweet dark soy sauce. Leftover orh kueh can also be enjoyed in the same way. See photos of my pumpkin kueh, stir-fried with eggs here.

STORAGE

Orh kueh keeps remarkably well. Once cooled to room temperature, it can be stored at room temperature for up to 1 day (depending on your climate), or 3-4 days in an airtight container in the refrigerator. For longer-term storage, orh kueh can be sliced, stored airtight, and frozen for up to a month. To reheat:

From refrigerator: Steam for 10-15 minutes or until heated through. Alternatively, you can pan-fry it to crisp up the outside.

From freezer: Steam it directly from the freezer for about 20-25 minutes or until heated through. It can be pan-fried after steaming.

Orh Kueh 芋粿 / Wu Tao Gou 芋头糕

Makes a 9-inch (22½ cm) round kueh