Nobody knows who the first person to ensconce vegetables in a rice batter and steaming the mixture into savoury cakes was, but the cook deserves our praise. Even though the most common entries in this genre are made with taro (orh kueh) or daikon (lor bak gou), my preference is for pumpkin kueh. Not only does mashed pumpkin turn the kueh exuberantly orange, it does not weigh you down the way taro would. It also imparts a beautiful sweetness that daikon is bereft of. The making of this kueh generally consists of the following steps:

Steam the pumpkin and mash finely.

Make a rice flour batter with the mashed pumpkin.

Fry the dried ingredients (e.g. dried shrimp, shiitake mushrooms, lapcheong).

Add the batter to the pan and cook until the mixture thickens to a stiff paste.

Transfer to a tin and steam until set.

The texture of the kueh is the trickiest thing to nail - softly solid and yielding easily to teeth, yet slightly springy and definitely not mushy. This is dependent upon multiple factors - the moisture content of the mashed pumpkin, types and ratios of flour used, and how long the batter is cooked for. Of these, the most unpredictable is the first. It’s tradition for Wex’s family to make this kueh in large tins regularly and every once in awhile, his mom would bemoan the texture of a particular batch for being too soft as a result of a waterlogged pumpkin specimen. While it is not always easy to determine the quality of a whole pumpkin when you buy it, steaming and tasting its flesh is a failsafe method - as long as your pumpkin is dense-fleshed, flavourful on its own, and vibrantly orange, it’s good enough for pumpkin kueh. If it is weeping water or lacking colour and natural sweetness, save your time and effort and make something else. Butternut squash is also a good substitute.

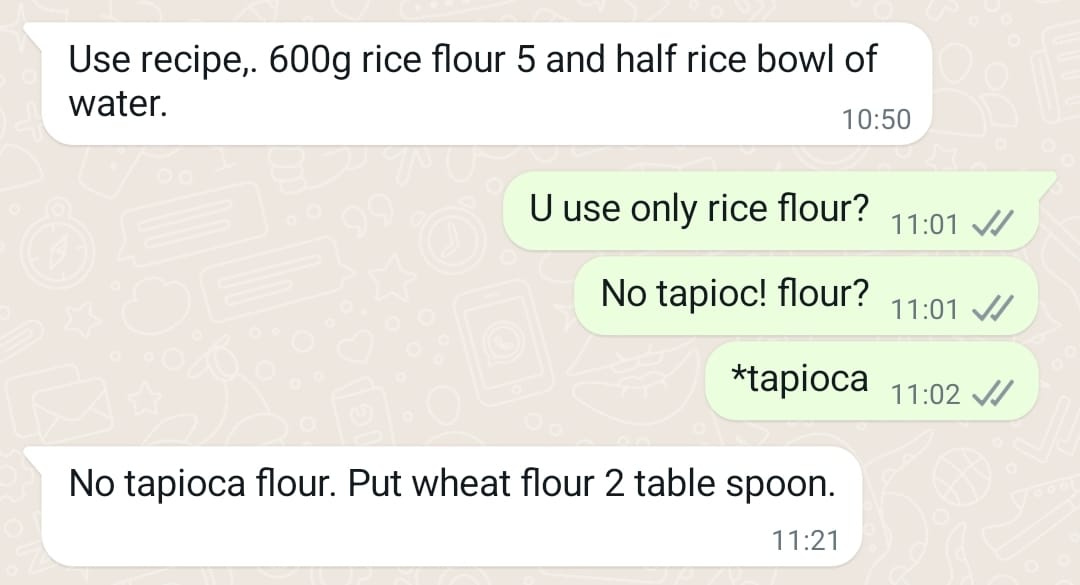

Apart from pumpkin, rice flour is the other main ingredient of the batter - it is what accounts for the kueh’s tenderness. As a starting point, Wex suggested asking his mom if she has a recipe and so I did. Because her measurements were pretty imprecise, as is expected from a Singaporean mom, we later spoke on the phone and the conversation fell into a comical cliché. “How much is one rice bowl of water?” “Oh you know, the blue and white bowls that we use at home.” “600g rice flour to how much pumpkin?” “One big pumpkin from the market.”

Based on one guesswork and the proportions that she provided, I did a series of small-scale experiments. My mother-in-law uses wheat starch with rice flour in her batter, presumably to add a light bounce to the finished kueh. As the internet was split on tapioca flour and wheat starch, I went for the former and was pleasantly surprised that only a very small amount of tapioca starch is needed to produce a very satisfying soft chew. Any more and the kueh was overly springy, more Q than tender.

The kueh derives most of its flavour from intensely umami dried ingredients such as dried shiitake mushrooms, lapcheong (Chinese sausage), and dried shrimp. Because these are pricey, the main complaint that you’ll hear about most store-bought kueh is that they are stingy on these ingredients. At home, however, you can be as generous as you desire. To further boost the flavour of the kueh, I used a combination of the water from soaking these ingredients and collected from steaming the pumpkin as the liquid component of the batter.

Once the dried ingredients are fried, the batter is added to the pan and the mixture is cooked until it thickens. While some recipes (such as the lor bak gou on Hot Thai Kitchen and The Woks of Life) skip this step, I chose to cook the starches until they gelatinised to avoid them settling in the batter as it steamed. Generally, the longer the batter is cooked on the stove, the stiffer it gets, and the firmer the resulting kueh is.

Descriptions on the endpoint to look out for vary from recipe to recipe. My preference is to cook the batter until it forms a thick clay-like mixture holds its shape; when picked up with a wooden spoon, it shouldn’t fall back down into the pot. The mixture is then smoothed into a pan and steamed until the top is set. To test the doneness, one can insert a skewer into the kueh’s centre. Unlike most baked cakes, however, the kueh will not produce a clean skewer when done - cooked bits of batter clinging onto it is completely normal and to be expected.

Fresh out of the steamer, the internal structure of the kueh is very delicate. Allow it to cool completely in the pan to set before unmoulding and slicing. It can be enjoyed at room temperature or slightly warmed. I like to sprinkle over some spring onion, chopped chilli, and fried shallots as a garnish and serve the kueh with sambal.

The best part about this kueh is how it keeps for days in the refrigerator - ready to be reheated by steaming or frying until the edges crisp up (my favourite) for a quick snack. Otherwise, you can make a speedy version of the Singaporean hawker favourite fried carrot cake by dicing the kueh roughly and frying it with eggs, chopped garlic, and kicap manis. It also freezes terrifically.

Pumpkin Kueh

MAKES A 9-BY-4-INCH (23-BY-10-CM) KUEH