✨ Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a newsletter dedicated to celebrating Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every Monday, you’ll be receiving a tasty mix of food history, stories, and recipes straight in your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. This newsletter is 100% reader-funded; each paid subscription supports the writing and research that goes into the newsletter, pays guest-writers, and gives you access to all content and recipes. Thank you for being here and enjoy this week’s post. ✨

Spring rolls are so named because they traditionally herald spring and the arrival of fresh vegetables. While most people are familiar with the deep-fried variant, I don’t suppose many outside of Asia are aware of the fresh spring rolls known as popiah 薄饼. While deep-fried spring rolls measure around three inches long and are enjoyed as snacks, each popiah is burrito-size and are meant to be enjoyed as the main event of a meal. Absent are the crispy, crackly wrappers that shine with oil; the silent star of the show here is really the wheat wrappers, tender and delicate, yet providing sufficient tensile stretch to accomodate a generous amount of filling without tearing.

Popiah is unique to Fujian province—the homeland of the Hokkiens—in China. It was originally conceived as a springtime dish to celebrate the abundance of vegetables, such as jicama, bean sprouts, carrots, lettuce, and beans. During the Tomb Sweeping Festival—which coincides with spring—there was historically a ban on using fire, leading to the tradition of eating room temperature food such as popiah on this day. With the movement of Hokkien immigrants in Asia, many variations exist as each food culture has made these rolls its own. In Singapore and Malaysia, popiah is made with braised daikon and jicama, lettuce, and cucumber. Prawns, and in some cases finely shredded lapcheong (Chinese sausage), tend to be added but the meat or seafood is not the star, true to the original intention of the dish. There is also the Taiwanese runbing 润饼, which, according to Made in Taiwan by Clarissa Wei and Ivy Chen, is made with an assortment of julienned vegetables and pork. The Philippines also has their own version called lumpia, introduced by early Hokkien immigrants and traders, that is often doused in sauce.

The popiah wrapper is the one stubborn food item that stands defiantly in the face of an industrialised food system, and I love that about it. More than one overseas Singaporean has asked me if they can use ready-made spring roll wrappers for homemade popiah. While you can find spring roll wrappers or Asian-style crepes sold frozen in packages, it has never occurred to me to purchase them for popiah because the pleasures of a perfectly pliant popiah wrapper are far too elusive and delicate to store. Even artisans and hawkers who specialise in making popiah skins advise their customers to enjoy the wrappers on the same day.

In Singapore, when cooks want to throw a popiah party, they don’t make their own popiah wrappers; they get them from the hawkers. The reason for this is the amount of time and skill that is required. Even though the wrappers call for the most basic of ingredients, it takes a practiced hand to sling the sticky dough around one’s wrist and smear it onto a hot griddle to form each wrapper.

While I don’t regard this as something that is insurmountable for the home cook, it does require the dough to be well-worked; a dough that does not have enough stretch will not be able to lift from the pan in a single mass with a jerk. Not being the owner of a stand-mixer in my kitchen has forced me to get creative. In a past newsletter, I shared about an improvised method of “painting” a thick batter onto the pan. I first read about it in Made in Taiwan and, later, a reader told me that she had seen it in a documentary. While this produces a crepe that is texturally very similar to what you get at Singapore’s hawker centres, it demands a certain level of fastidiousness when it comes to heat control. If the pan gets too hot, the crepe browns and sets before the “painting” is complete. It also takes time and, seeing that I was cooking for six over the weekend, I figured that there had to be a better way.

Enter egg-based popiah wrappers. While most Singaporeans are familiar with the traditional Hokkien popiah wrappers, Straits Chinese cooks prepare theirs with a batter made with a blend of tapioca flour, wheat flour, and egg. The technique is similar to that of making French crepes: The batter is added to a pan and swirled to coat its base with a swift rotation of the wrist. When set, the crepes are almost edible paradoxes, simultaneously retaining the stretch of the original Hokkien wrappers, while being far more tender and plusher in mouthfeel. One of our guests, when asked to search for a word, described them as “fluffy”. While leafing through I Am a Filipino by Nicole Ponseca and Miguel Trinidad, I noticed—to my surprise—that there are similarly more than one type of lumpia wrappers in the Philippines. One is very similar to the Hokkien wrappers in Singapore, and another is egg-based, like the Straits Chinese version, but made with a blend of rice flour, all-purpose flour, cornstarch and coconut milk in place of water.

The key to making this style of wrapper, I’ve realised, is getting the consistency of the batter right. By keeping it thin, you’re able to coat the pan evenly and quickly, thus allowing for a remarkable membrane-like texture. One of our guests who’s Dutch compared it to the smooth skins that are pulled over drums. When he said that, I felt particularly struck by how the use of the word “skin” 皮, rather than wrappers, that we commonly use to describe these crepes in Singapore is so apt and poetic.

However, there’s a limit to how thin the batter should be. When the batter is too watery, the crepes develop craters the moment they hit the pan. In something like a bánh xèo—where the intention is to get the crepes as crispy as possible—the lacy, crater-like pattern is a desirable trait and, when there’s sufficient oil in the pan, eventually results in whisper-thin, gyoza wing-delicate crepes. But in popiah wrappers—as I later learned when we came to wrap our popiahs—it is impossible for those made from too-thin batter to contain much filling without tearing.

Being very tender, one needs a delicate approach to prevent the egg-based wrappers from sticking to one another. The obvious solution is a sheet of waxed paper in between each crepe, but a more environmentally friendly way to do this is to cool the wrappers until they are barely warm, before stacking them up with a strand of garlic chive in between as insurance against sticking. Because they dry up the longer they are exposed to the air, the featherweight skins should be kept under a damp kitchen towel until called into service.

Popiah is the kind of dish that demands a party, for its many components means that it is a meal that is so labour-intensive to make that you must invite others to share in the pleasures of the table with you. Every popiah cook has their own combination of toppings and sauces. Wex’s mother—by now a veteran thrower of popiah parties—offers sweet sauce, a chilli sauce made with ground red chillies, and garlic paste for guests to smear all over the wrappers. My personal favourite trifecta of sauces is kicap manis, dried shrimp sambal, and garlic paste. Crushed peanuts, braised daikon and carrot (set in a colander so that excess moisture drips off, thus lowering the chance of the popiah bursting), shredded cucumber, lettuce leaves, omelette strips, homemade crispy bits, steamed prawns, and coriander leaves are for guests to add to their wrappers before the popiah is rolled up tight. This style of serving where everything is on the table and everyone assembles their own plate of food is my favourite format for feeding people—it is interactive, accomodating of dietary restrictions, and always a whole lot of fun for both the host and guests.

The recipe for the popiah components can be found in this past post on popiah, and I have provided the recipe for the egg-based wrappers below.

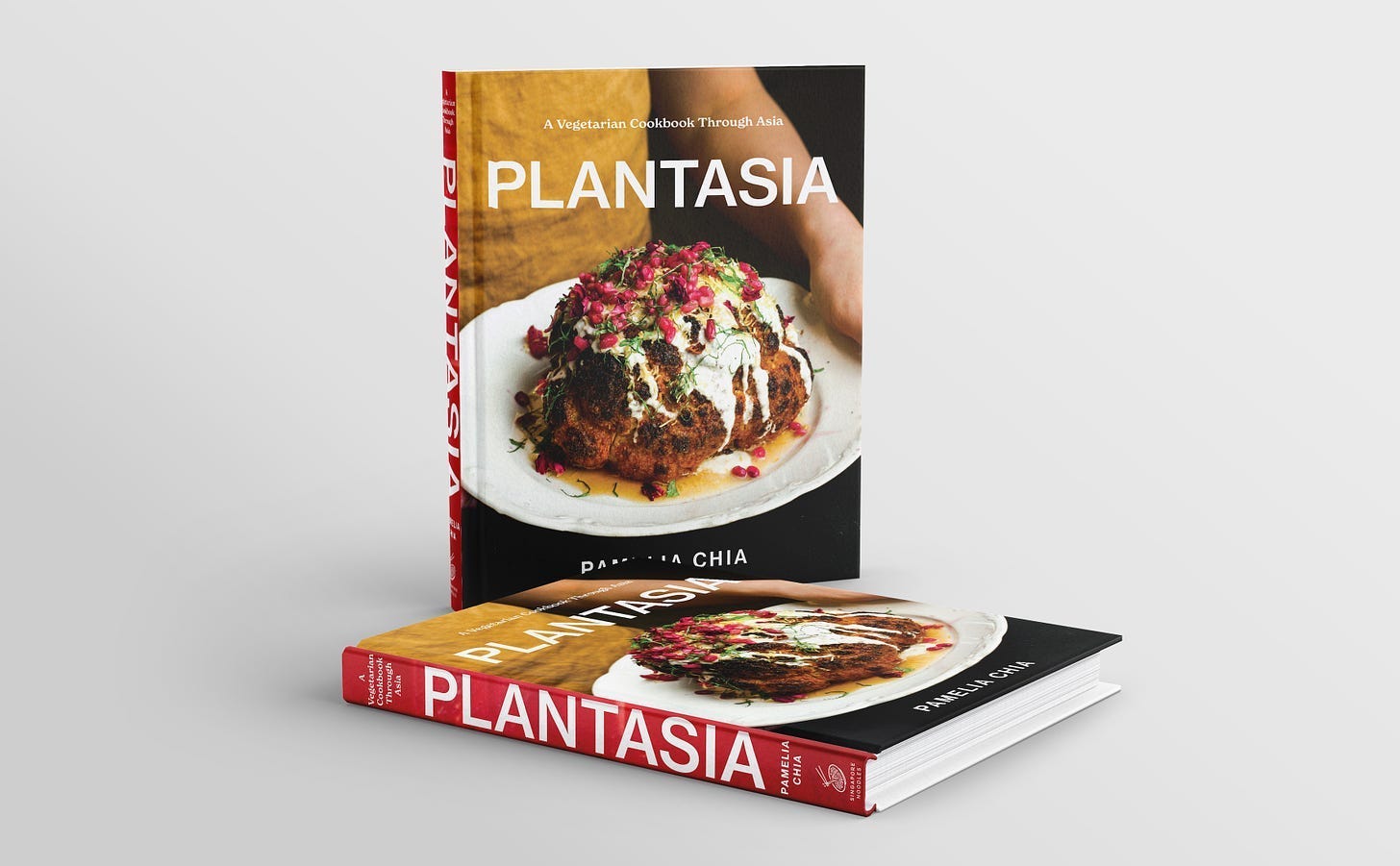

🥦 My second cookbook Plantasia: A Vegetarian Cookbook Through Asia leverages Asia’s techniques and flavour combinations to expand your repertoire of vegetable dishes deliciously beyond Western-style salads. Pick up your copy here or find a stockist near you. It is mostly vegan (or easily veganised), with plenty of allium-free options.

Egg-Based Popiah Skins

Makes 25 to 30 skins