Mianjin 面筋: Part I

Plantasia: A Vegetarian Cookbook Through Asia was officially launched this past weekend! In line with the vegetarian theme, I’ve invited Mun Yi, a passionate Singaporean home cook based in the US, to share about wheat gluten (also known as seitan or mianjin 面筋). This is the building block of many vegetarian dishes in Singapore, including my favourite hawker breakfast dish - vegetarian beehoon with cabbage, black fungus rolls, mock char siu and crispy ‘goose skin’.

Inspired by her Buddhist background, Mun Yi’s personal food project, The Fallow Season, makes space for mindfully grounding the body through the hands-on experience of making slow food. She creates 'fallow' moments amidst the hustle of modern life and captures these unhurried (and unhurry-able) food processes on film. Follow her sojourns into the world of slow food such as soy sauce, preserved vegetables, tofu and miso on YouTube and Instagram.

Rediscovering mianjin

By Mun Yi

I grew up in a Buddhist family of vegetarians, and it all began with my aunt (also my godmother). She had initially turned vegetarian in the 1980s when my grandmother was due for a cataract surgery. As a way of accumulating good ‘merits’ or karma for the procedure, she took a vow to be a strict zhai 斋 vegetarian. Unlike su 素 vegetarianism, which is simply the avoidance of meat, zhai 斋 vegetarianism is strongly associated with religiosity. In addition to adhering to Buddhist precepts, zhai vegetarians are required to abstain from the ‘five pungent plants’ 五辛, which include garlic and onions. To make up for the lack of animal protein and alliums, the cuisine leans heavily on fermented sauces, condiments and dried shiitake mushrooms.

At that time, the landscape of Chinese vegetarian food in Singapore was sparse. Even though renowned Chinese vegetarian restaurants like Loke Woh Yuen and Fut Sai Kai had been established since the 1940s, locating casual hawker-style Chinese vegetarian fare in the HDB heartlands was challenging.

"It was very tough back then. I basically had to cook everything I ate," my aunt remarked about the lack of affordable and readily available vegetarian options. A larger obstacle still was a lack of understanding within her social circles. In the 1980s, even though meat might have been a luxury at dinner tables, abstaining from it entirely was often misconstrued as penance for notable moral failings.

“The neighbourhood bully somehow found out that I was a vegetarian. He would come by your grandfather’s provision shop and loudly ask what the misdeeds I’d committed to necessitate being vegetarian,” my aunt recounted.

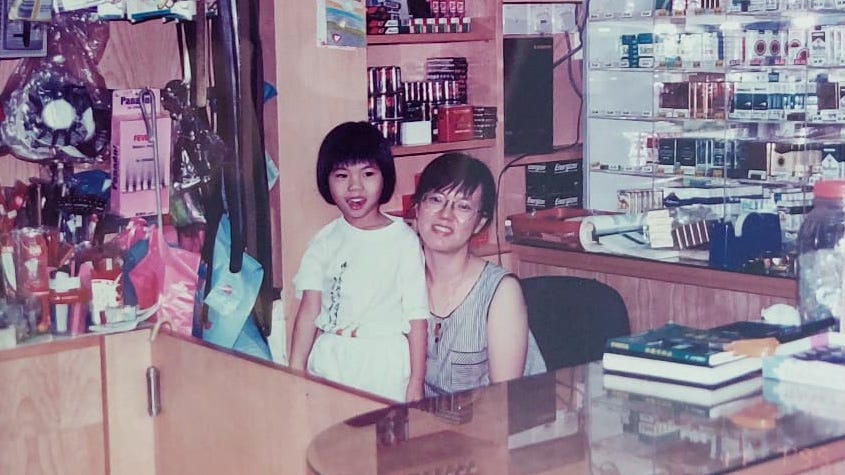

My family’s store

My grandfather owned a provision shop near Kallang MRT station. Recognising the scarcity of flavourful vegetarian options in the neighbourhood, my family began retailing vegetarian ingredients, particularly as my mother and two other aunts had also come to embrace vegetarianism. While my grandparents might not have fully understood why, they were supportive of their daughters’ choices.

“Many vegetarian ingredients on the market then were not intended for everyday consumption. They were meant as ancestral offerings and quite unpalatable,” said my aunt. In land-scarce Singapore, Chinese ancestor remains were relocated from in-ground cemeteries to Buddhist temples and columbariums, which only allowed for vegetarian offerings. Living descendants of the deceased thus replaced traditional meat offerings with vegetarian ones, leading to mock meat products such as an entire chicken complete with head and comb, and realistic mock duck replete with mottled skin. The emphasis was on verisimilitude, not flavour.

“When we started selling vegetarian ingredients, our aim was to offer good-tasting products to other Buddhist friends in the area,” explained my aunt. Having spent many childhood afternoons in the provision shop, I became intimately acquainted with the vegetarian products - and in particular, those made with mianjin.

Mianjin

Many older Singaporean Chinese folks cannot envision vegetarian food without mianjin-based mock meats. This humble ingredient dates back to the 6th century CE, during the Han Dynasty in China, when the introduction of Mahayana Buddhism via the Silk Road led to widespread adoption of vegetarianism and development of Chinese vegetarian cuisine.

I did not enjoy mianjin as a child, associating it with heavily seasoned mock meats - dense slices of ‘chicken thigh’, pink-hued ‘hams’ and stewed seaweed ‘fish’. However, following a recent conversation that I had with my aunt, I felt inspired to explore the world of zhai vegetarianism anew. In particular, I was interested in the inventive ways of preparing mianjin.

What is unique about mianjin that makes it such a great meat analogue? Its distinctively bouncy and chewy gluten texture is key. Here’s the science behind it. Wheat flour contains two proteins: glutenin and gliadin. When activated by water, these proteins link together to form gluten networks. A gluten network can naturally develop in a dough over time, or can be expedited by kneading the dough. Adding a small amount of salt further strengthens the gluten network by tightening and compacting it.

As the dough undergoes stretching and kneading through successive changes of clean water, starch dissolves away, leaving a stretchy, rubber band-like gluten network behind. The texture is embodied in its name, translating to 'wheat tendon'. At this stage, the basic form of mianjin serves as a blank canvas, and depending on the cooking techniques employed, can transform into a variety of gluten products, each with its unique texture and use.

Different forms of mianjin

Oil mianjin 油面筋 and kaofu 烤麸 stand out as two intriguing mianjin variants that capitalise on its unique chewy texture without aiming to be a meat substitute.

In the making of oil mianjin, a basic mianjin dough is divided and shaped into small balls before deep frying at a relatively low temperature. Frequent rotation ensures even cooking as the balls puff up to several times their original size. Oil mianjin has a fluffy, aromatic quality, and its golden-brown exterior adds an additional crispness and bite. Think of it as akin to the difference between a deep fried fish ball and a regular one.

In the making of kaofu, mianjin (or vital wheat gluten flour) is kneaded with sugar and yeast and allowed to ferment. As the yeast consumes the sugars, it releases carbon dioxide, creating tiny air pockets throughout the mianjin. Once it has doubled in size, it is delicately steamed. These kaofu cakes, light and porous, provide a chewy experience without a sense of heaviness or rubberiness and adeptly absorb sauces, curries, and broths, similar to a chewy taupok.

In Singapore, my friend’s mother purchases readymade oil mianjin balls at Yue Hwa Department Store in Chinatown and adds to their family’s chap chye dish to sponge up the sauce and provide a contrasting chew and bite. She might even throw in some canned mianjin and peanuts for a ‘deluxe’ chap chye experience.

My childhood was saturated with experiences of mianjin, chiefly as a mock meat in Chinese vegetarian cuisine. Initially this led to an aversion towards it. However, my perspective has evolved as it is clear that cooking with mianjin requires a nuanced appreciation of the ingredient itself. Embracing mianjin means celebrating its unique qualities and textures, moving beyond its simplified classification as merely a meat substitute and unlocking its culinary potential in its own right.

The following recipe yields a dense mianjin that can be seasoned and sauced to resemble meat. It is the base from which kaofu and oil mianjin balls are made.

Here I’ve included two methods for making it. The “washed flour” method uses just wheat flour, water and salt. Each 100g of wheat dough typically will yield about 25g to 30g of mianjin, with the remainder being wheat starch and water. Don’t worry if this seems wasteful - the wheat starch that gets washed off in the process can be made into liangpi noodles. For a shortcut, use vital wheat gluten, which is pure gluten in powdered form. Both versions are detailed below. (Video tutorial here)

The washed flour method:

(Yields about 180g of mianjin)

350g high protein wheat flour, such as bread flour or whole wheat flour

(*You can also use all purpose flour, but it will yield about 150g of mianjin as it contains less protein.)

7g salt

245g water

Stir together 350g high protein wheat flour (such as bread flour or whole wheat flour), 7g of salt and 245g of water in a large bowl. Mix everything until it comes together in a rough, shaggy mass of dough, then knead the dough by hand until homogenous.

Cover the bowl with a wet kitchen towel or plastic wrap and let it rest for at least 4 hours, up to 8 hours. You can do this overnight if you wish.

After the long rest, the dough should be smooth and elastic. Try stretching it out with your fingers to form a “windowpane”. It should stretch easily without tearing.

Fill the bowl with the dough with clean water and begin “washing” the dough. Stretch and knead it as if you were washing clothes. The starch in the dough will begin dissolving into the water, and the dough will seem as if it is falling apart. Continue stretching and kneading it.

Once the water becomes almost opaque, pour it off into a separate container if reserving to make noodles, or discard. Refill the bowl with clean water and continue washing the dough. Repeat until the refilled water remains relatively clear, and you have a ball of raw mianjin in your hands. Squeeze out excess water from the raw mianjin. It should feel stretchy and a little tight, like a rubber band.

The vital wheat gluten method:

(Yields about 180g of mianjin)

80g vital wheat gluten

2g salt

100g water

Stir together 80g vital wheat gluten, 2g salt and 100g water in a large bowl. Using chopsticks or a spatula, mix everything until it comes together in a rough, shaggy mass of dough. Then, with clean hands, knead the dough until it is bouncy and smooth.

The raw mianjin is ready for use. If not using immediately, place the raw mianjin into a bowl of water to prevent sticking.

Check out Part II of this newsletter for how to deep fry mianjin into puffy golden oil mianjin balls, ferment and steam it into kaofu, and bring all of the techniques together in a revisited childhood dish - braised mianjin with peanuts.