Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every week, you’ll be receiving historical tidbits, personal stories, and recipes delivered straight to your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. My cookbooks Wet Market to Table and Plantasia are available for purchase here and here respectively. Thank you for being here, and enjoy this week’s post. ✨

Since I was young, my mom’s side of the family has had a ritual of gathering every Sunday at my grandparents’ house for dinner. The family’s big—my grandparents have seven children and eleven grandchildren—and throughout the evening, we would take turns eating at the dining table, while the rest watched TV in the living room.

In the past decade or so, however, my grandmother has become less mobile due to old age, and my Auntie Yokkie has taken up the mantle of cooking for everyone each week. According to my other aunts, she was never particularly interested in or gifted at cooking—but over the years, she has become a seasoned pro at navigating the wet market and a truly great cook. It just goes to show: cooking is a muscle that strengthens with practice, and being a good cook is more a function of how often you cook rather than something that you’re “born” with.

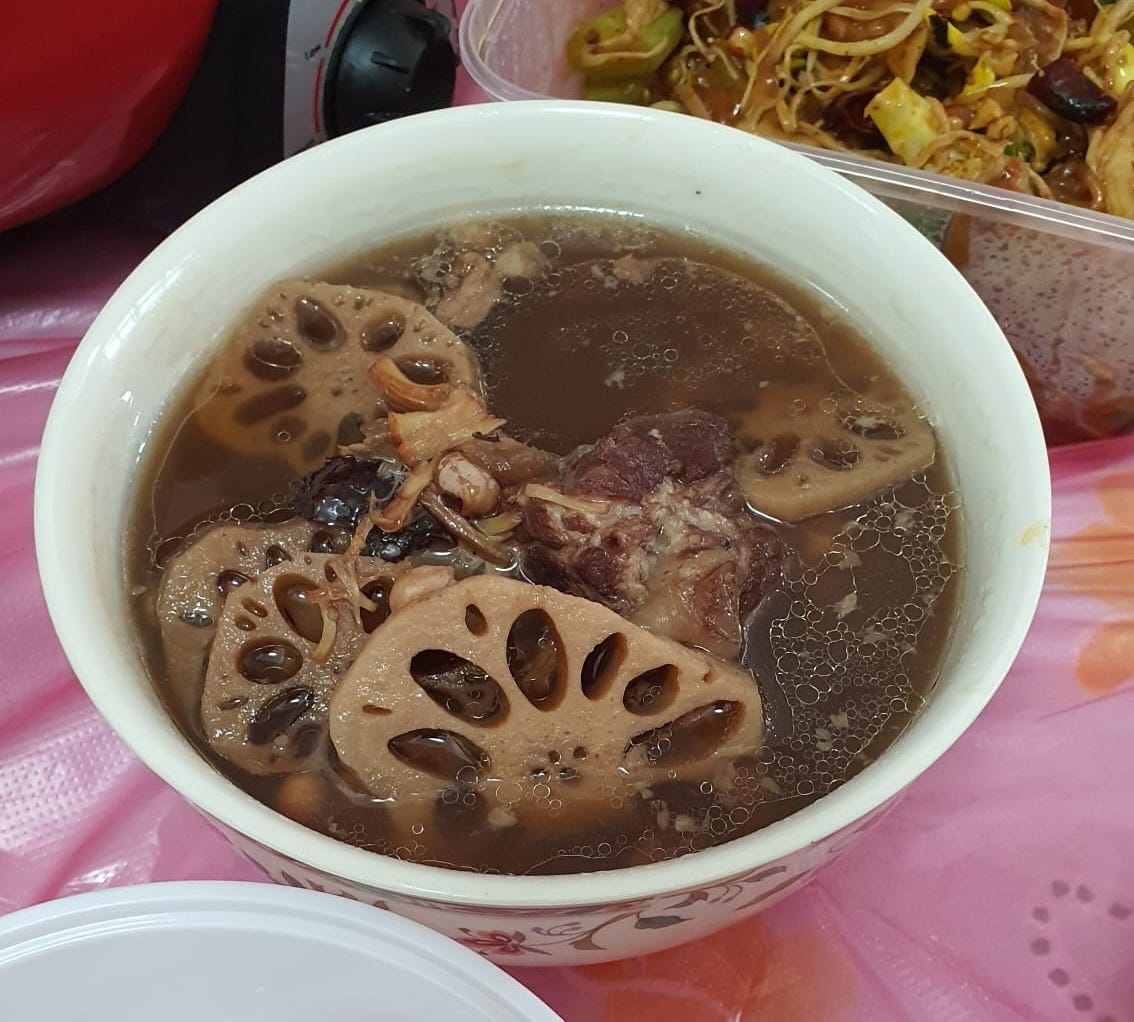

Whenever I’m back in Singapore, I join my extended family for these weekend meals. On a recent visit, I was floored by how good my aunt’s lotus root and spare rib soup (蓮藕排骨湯) was. Slow-simmered soups—also known as “old fire soup” (老火汤)—are at the heart of traditional Cantonese home cooking. Of these, lotus root soup might be the most classic and enduring. I thought of it so much after returning to the Netherlands that my aunt bought me some dried octopus and black beans and sent them over via my sister.

While lotus root soup is a foundational dish—one you’d find in almost every hawker centre and Chinese home—my aunt’s soup demonstrated that there are nuances that separate a memorable one from the pack. Over Whatsapp calls and texts, she taught me to make it her way. I don’t make Cantonese soups as often as I should because of the time investment, but when we sat down to this pot of lotus root soup, the hours of simmering felt entirely worth it.

Enjoy,

Pamelia

COOKING WITH LOTUS ROOT

Lotus root sits at the heart of this soup—more central even than the meat. You can substitute pork with chicken, or use a mix of both if you prefer, but swap out the lotus root for something else, like daikon or carrot, and the soup simply ceases to be what it’s meant to be.

But first, what is lotus root? Nearly every part of the lotus plant is used in Chinese cuisine: lotus seeds are made into sweet paste for mooncakes and steamed buns; lotus leaves are used as fragrant wrappers, much like banana leaves. Still, it’s the lotus root—the large, edible stems of the lotus plant—that’s the most prized. A whole lotus root resembles a chain of sausage links, with each root comprising three to five tubers. Beyond its thin brown rind, lotus root reveals a pale interior and a beautiful, lacy pattern. Raw, it’s crisp and slightly sweet, reminiscent of jicama. When cooked, it becomes tender and starchy—like a cross between taro and potato—but retains a distinctive crunch. One unique trait is its stringy sap, which forms fine, silk-like threads when bitten into.

Why is lotus root used in soup? Lotus root is ideal for slow-simmered soups because it absorbs flavours beautifully while retaining its crunch. Unlike many vegetables that go soft or fall apart after long cooking, lotus root holds up. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), it’s believed to have cooling properties, nourish the lungs, and promote blood circulation. It’s often featured in soups meant to balance the body’s yin and yang—especially during seasonal transitions. Nutritionally, it’s rich in fiber, vitamin C, potassium, and beneficial phytonutrients.

How to shop for lotus root? Look for lotus root that is firm and heavy without cracks, cuts, or bruises. The swollen root hides within the mud, thus it is typically found in markets caked in mud—the ones still caked in mud will keep longer compared to the cleaned ones. If you live overseas, it can be tempting to buy frozen lotus root for this soup, but don’t. Freezing compromises its cellular structure, making it more fragile and prone to breaking apart during long cooking. Presliced frozen lotus root is especially delicate and won’t stand up to the slow simmering needed for this soup. Save those for quick-cooking dishes like hotpot instead. I found fresh lotus root in the refrigerated section of the Asian grocer, where they are sold in vacuum-sealed plastic packages.

How to prepare lotus root? If your lotus root comes covered in mud, scrape and scrub thoroughly before rinsing. Peel off the skin, then rinse it thoroughly before cutting. Once sliced, the pale interior oxidizes quickly and can turn brown when exposed to air, so use it immediately after cutting.

ALL ABOUT THE MEAT

Pork ribs are the usual cut used for soup-making. My aunt uses specifically “soft bone” 软骨. This refers to pork ribs with tender cartilage that turn rich and gelatinous upon simmering. If you shop at the wet market, tell your butcher that you’re making soup and you’re planning to eat the meat after boiling so that he gives you the right cut. If you live in the West, you can ask for pork rib tips—the smaller, more cartilage-heavy pieces at the end of the ribs, which are ideal for soups and stews. Otherwise, pork spare ribs work just fine. Don’t get soup bones; Cantonese soups are often made with a decent amount of meat around the bones for flavour, plus the meat will become so tender and delicious at the end of simmering.

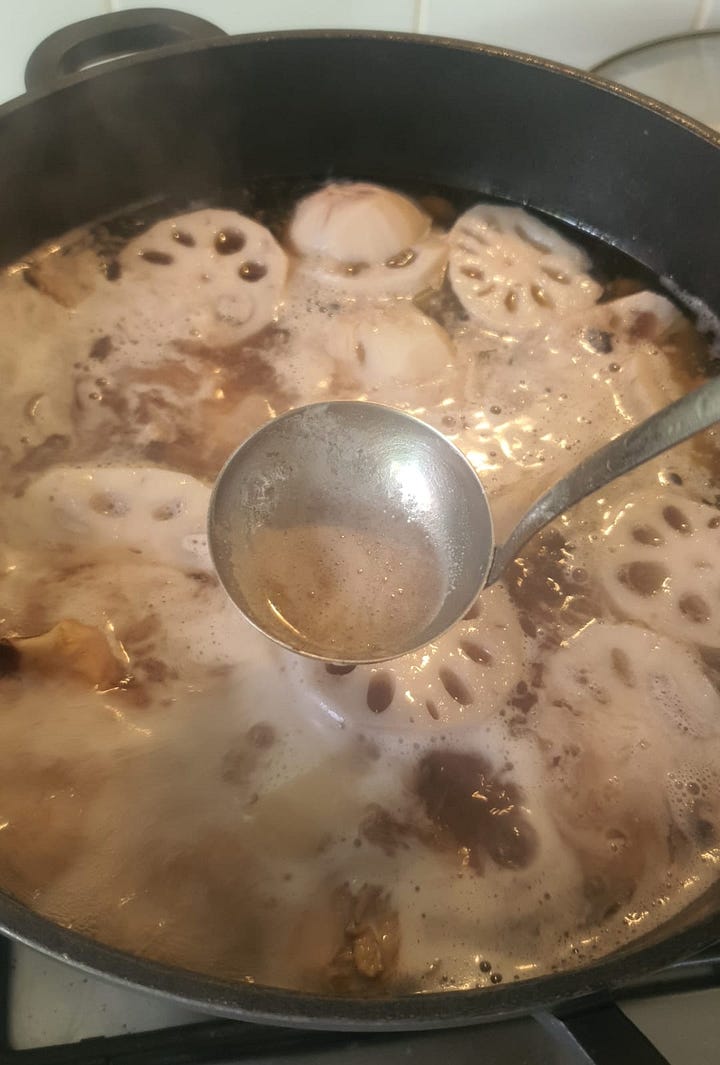

Cantonese soups are prized for their 清 quality—meaning clear, light, and pure. Raw bones and meat contain blood, bone fragments, and surface proteins that, when simmered directly, cloud the broth and create scum. Blanching the meat is a foundational step in achieving a broth free of impurities and excess grease. To do this, bring a large pot of water to a rolling boil and add the meat. Once the water returns to a boil, you’ll see scum rise to the surface. At this point, drain the meat, rinse it thoroughly under cold water, and scrub the pot clean to remove any remaining residue before starting the actual soup.

THE UMAMI: DRIED SEAFOOD

There’s a whole range of dried seafood that the Cantonese use in soup-making—dried scallops, dried clams, dried squid—but my aunt’s preference is for dried octopus (章魚), which takes the soup to another level. Dried octopus is whole octopus that has been salted and sun-dried until it becomes leathery and stiff. When simmered slowly, it infuses the broth with an oceanic, umami depth. While some recipes recommend soaking it first, my aunt skips that step entirely. Instead, she cuts it into four or five pieces for easier handling, then toasts it in her toaster oven or air fryer until it’s intensely fragrant and slightly crisp before adding it to the pot. A hot pan works just as well.

TIME, THE MOST IMPORTANT INGREDIENT

There are a few ways you can cook your soup:

Double-boiler: Here, the soup is cooked in a vessel set over a simmering pot of water, creating a gentle heat that mimics steaming. While the indirect heat is ideal for extracting nutrients and flavours without overcooking or breaking down the ingredients too much, the downside is that you need to be vigilant in ensuring that the water in the bottom pot doesn’t evaporate completely. Being so gentlr, this method also lengthens the cooking time.

Conclusion: Great for making chicken essence, but impractical for lotus root soup.

Pressure cooker: Pressure-cooking cuts the cook-time to 30-45 minutes, however the rapid cooking process doesn’t allow the same depth of flavour to develop as in slower methods. Given that the soup is under pressure, it can also be easy to overcook or over-extract flavours (especially with delicate ingredients like lotus root) and result in a murky broth.

Conclusion: A good option for time-pressed cooks, but you compromise on clarity, flavour, and texture (lotus root might be overcooked or the broth may be murky).

Cooked in a pot set over the stove: This is the classic method that allows you to adjust the heat and skim off any scum as needed. My aunt simmers hers for 3 to 4 hours on the stove to coax out every bit of flavour and medicinal properties from the ingredients.

Conclusion: Ideal method if you have 3-4 hours to spare.

Cooked in a pot set over charcoal: A cooking method for those with outdoor kitchens, charcoal fire starts off intense enough to boil the soup, then slowly burns down to maintain a gentle simmer.

Conclusion: Not practical for all kitchens, as it requires outdoor space and specialized equipment like a charcoal stove or burner.

Slow-cooker: The beauty of a slow-cooker is that once the prepped ingredients are added, it can be left to cook without supervision, overnight or during the day while you work.

Conclusion: Convenient, hands-off process, but you’ll need to plan in advance.

When the soup is ready, it will taste intensely flavoured, the meat will be falling off the bone, and the lotus root will have turned a purplish beige from absorbing the savory broth. Serve with saucers of sliced red chilli (or bird’s eye chilli) in soy sauce or—my favourite—sambal belacan.

Lotus Root Soup

Serves 6