✨ Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a weekly newsletter dedicated to celebrating Asian culinary traditions—the traditional cooking techniques, rich food histories, and personal stories that make each dish more than just a recipe. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. This newsletter is 100% reader-funded; your paid subscription directly supports the writing and research, pays guest contributors, and gives you access to all content and recipes. As the newsletter grows, I’m eager to expand our community of guest contributors who will share their expertise and food stories with you. Thank you for being here and enjoy this week’s newsletter! - Pamelia ✨

For most of my life, persimmons had a singular shape, taste, and texture: squat like a tomato, sweet, and tender-crisp like a cross between Nashi pear and nectarine. This variety, widely cultivated throughout Asia, is often known as the Fuyu persimmon. Upon moving abroad, I encountered a different variety: the Hachiya persimmon. Unlike Fuyus, Hachiyas are elongated, resembling a human heart in size and shape. Colour is not a good marker of ripeness for these—we learnt this the hard way when we bit into a specimen that was appealingly orange, yet was so astringent that the insides of our mouths instantly turned to sandpaper. What we did not know then was that Hachiyas are ripe only when they feel truly squishy, their juice and gelatinous pulp suspended within a thin skin-membrane like a water balloon.

To eat a Hachiya is, thus, an exercise in patience. You wait weeks for your reward. For days, I prod the persimmons with my fingers to ascertain their ripeness, and even when they are as soft as a freshly plucked sun-ripened tomato, I tell myself to give them more time. Eventually, when they feel like they are literally on the verge of bursting, I gently pull it apart with my hands over a bowl to catch the juices and dig in. A ripe Hachiya is so soft, it needs only a spoon. The Fanta-orange flesh within tastes like so much accumulated sunshine that a simple fruit turns into an indulgent thing to enjoy in dreadful weather. I love eating the jellied pulp with kwark, a soft yoghurt-like cheese that’s popular here in the Netherlands, or frozen and slightly thawed like a sort-of sorbet.

Good as these are, the real reason I look out for the arrival of persimmons every autumn is to make hoshigaki 干し柿—something that requires even more patience. Drying persimmons is not a practice exclusive to Japan; China and Korea also share in this tradition, with their products being known as shì bǐng 柿饼 and gotgam 곶감 respectively. Before processed sugar became commonplace, these treats were nature’s own candy for country folk.

When persimmon trees in Japan get heavy with orange fruit, entire families gather to peel and hang them in the cold autumn air. Hachiya persimmons are ideal, as they are sturdy enough to be peeled and hung compared to Fuyus. The tannins that contribute to astringency—what causes eaters of less-than-ripe Hachiyas to pucker with unhappiness—are, in fact, a strength in hoshigaki as their antimicrobial properties prevents spoilage. The tannins diminish gradually as the fruit slowly dries, leaving behind a caramel-like, concentrated persimmon flavour.

There are two ways to dry the persimmons: by hanging them up with string, or by setting them on woven trays. Both methods demand good airflow all around the persimmons to mitigate the problem of bacteria, and the resulting dried fruit—depending on which method you choose—either end up teardrop-shaped or puck-like. The Chinese name shì bǐng 柿饼, translating to “persimmon biscuit”, is an allusion to the latter. Regardless of appearance, the trademark of these is their soft and chewy interior. This video by popular Korean Youtuber Maangchi showcases the two shapes of dried persimmon and their unique texture that allows for them to be stuffed:

Making hoshigaki has become a ritual for me in recent years because it is such a wonderful way to embrace the seasons and so therapeutic. I love the idea of putting in the initial work, then leaving the fruit to transform over days with minimal intervention. Also, a major side benefit is that hoshigaki can really beautify a home.

First, select your persimmons. Look for Hachiya persimmons that are orange but stiff to the touch. Ideally, they should have their stems intact for the strings to be attached, but in the absence of one, you can push a long, stainless nail deep into the fruit. I purchase them from the Middle-eastern grocer because there’s always many to choose from and always cheaper than buying them from the supermarket. With a peeler, remove the skin, making sure to go under the calyx. The skin becomes very dry and leathery, close to inedible, by the end of the process so you want to remove as much as this impediment as you can. Once peeled, tie a piece of string onto each stem. The length of the string depends on where you’d like to hang the persimmons; I typically go for at least a metre long. Because tying persimmon stems with string requires as much dexterity and concentration as threading a needle, I find it easiest to make a loose loop first before hanging it on the stem, pulling it tight, and finally performing a second knot to ensure that it’s secure. Gripping the persimmons by their strings, sterilise the persimmons by dipping them into strong alcohol, such as vodka, or into boiling water for about three seconds before hanging them up.

To hang the persimmons, anywhere with good ventilation would work. I hang mine on the roller blind before my kitchen window, but you can improvise with a pole, metal shelves, or laundry racks. The dry, chilly winter this time of the year is perfect for the drying process and helps to keep flies away. If you make hoshigaki in warm weather, the persimmons will ripen, mold, or ferment before the fruit dries sufficiently.

Leave the persimmons for a full week without touching them; they will dry, soften, and deepen in colour. From the second week onwards, massage each with clean hands for a few seconds everyday to help break up the pulp within and redistribute the moisture and sugar. It is this diligent massaging that results in the migration of sugar to the surface of the persimmons, and a subsequent natural sugar bloom covering that resembles—fittingly for the season—frost. It will take about a month for the hoshigaki to be ready.

I had intended to postpone this newsletter until my hoshigaki are ready, so that I can show you photos of the entire process, but I’m sharing this early so that you can start before the fleeting persimmon season is over.

While we wait, I’ll share a recipe for another sweet treat that I made recently. Christmas to me is always a time of edible gifting, and that often means cookies! I made a batch of cocoa linzers with caramel centres infused with málà (numbing Sichuan peppercorns and dried chilli flakes) and sprinkled with roasted peanuts to echo the usual peanut garnish in málà dishes. I can’t take credit for this brilliant combination; I was inspired by those made by chouxandsunshine. These are polarising cookies to say the least, but if you are a fan of sweet-savoury combinations or are a diehard chilli oil addict (the kind of person who drizzles chilli crisp over soft serve), then you’ll probably love these! Even if you aren’t, the cookies are terrific without the málà.

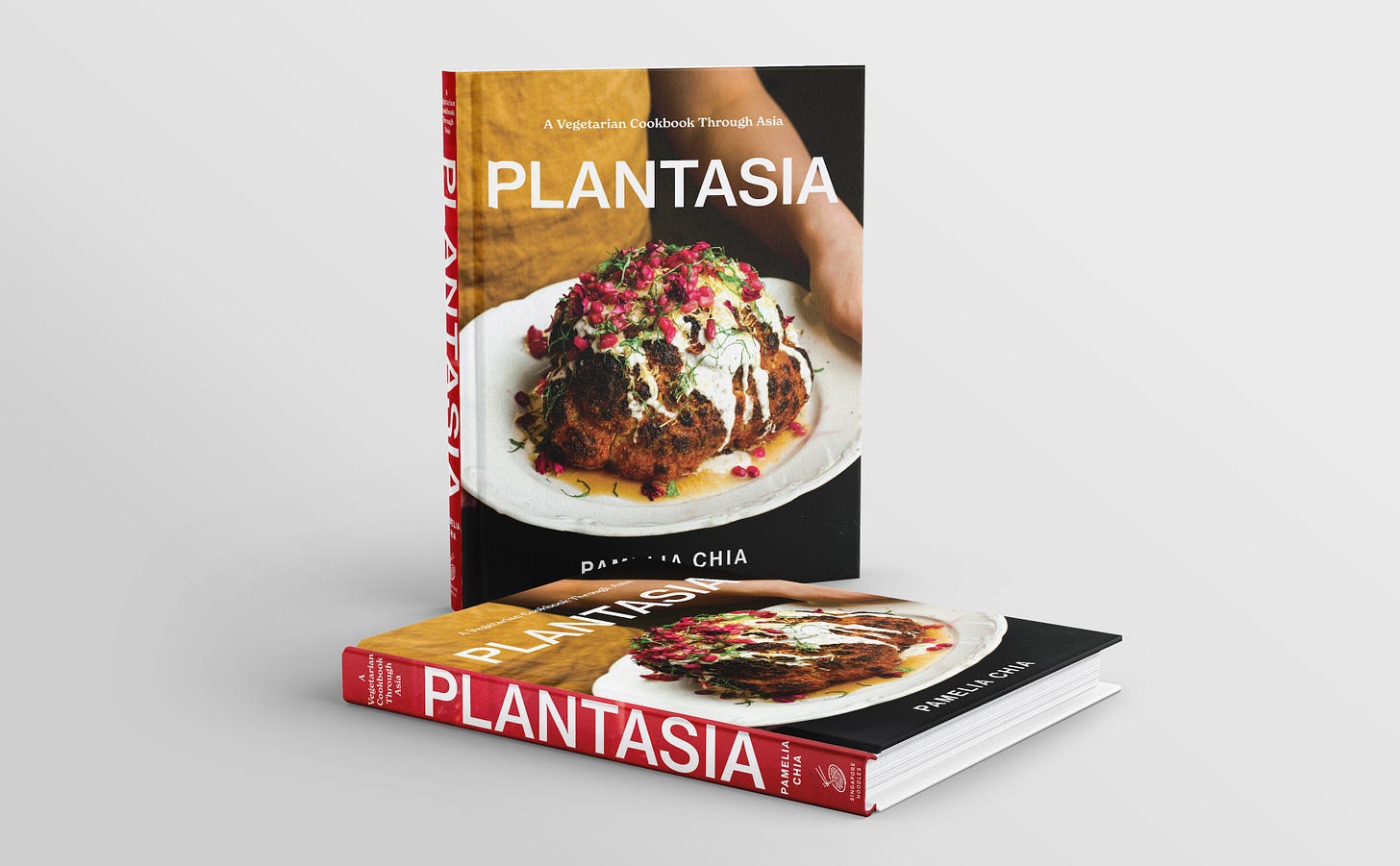

🎄✨ Christmas is around the corner! To celebrate, I’m offering a one-for-one deal on my cookbook Plantasia and 20% off all annual subscriptions leading up to the holidays.

Málà Cocoa Linzers

Makes 35 to 40 cookies