✨ Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a weekly newsletter dedicated to celebrating Asian culinary traditions—the traditional cooking techniques, rich food histories, and personal stories that make each dish more than just a recipe. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. This newsletter is 100% reader-funded; your paid subscription directly supports the writing and research, pays guest contributors, and gives you access to all content and recipes. In the lead-up to Christmas, I’m offering a 20% discount for annual subscriptions. As the newsletter grows, I’m eager to expand our community of guest contributors who will share their expertise and food stories with you. Thank you for being here and enjoy this week’s newsletter! - Pamelia ✨

A spin-off of Chinese jiǎo zì 饺子, gyoza 餃子 were introduced to Japan centuries ago, but only gained significant popularity after World War II. One widely accepted theory is that Japanese soldiers who had been stationed in China during the war brought back recipes for jiǎo zì. There is also speculation that the post-war love for gyoza was because, in a time of scarcity, it allowed for ground pork to be bulked up with cabbage, which was cheap at the time. Compared to Chinese jiǎo zì, gyoza are known for their thin skins and unique steam-frying technique: the raw dumplings are steamed and then fried in the same pan to produce crisp bottoms and juicy filling. I’ve been making gyoza for years now (I even have a recipe for them in my first cookbook), but my love for them was reignited when we moved to the Netherlands last year and came across Bibigo’s frozen gyoza at the Asian grocer. These were so juicy—almost as if they have soup injected into them—and crisped up so well, they set a new standard to aim for.

The meat patty

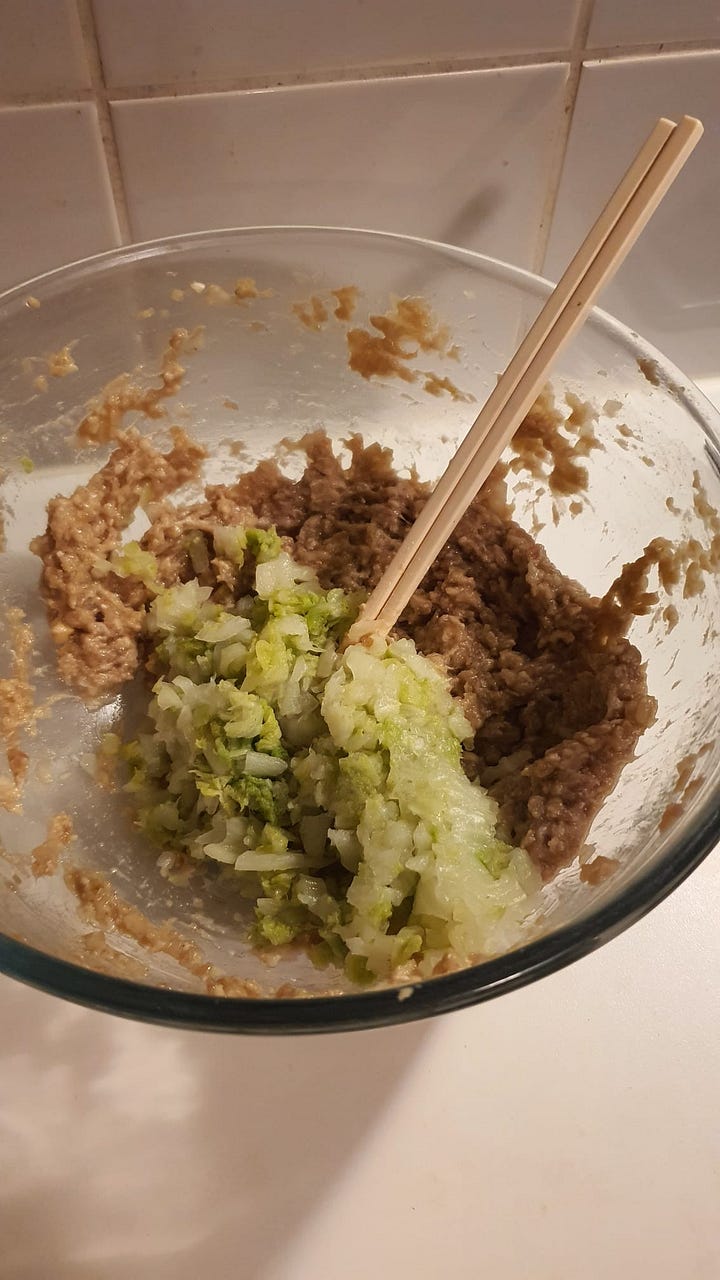

Gyoza filling is, in essence, marinated minced meat. Apart from the seasonings, it is common to add water and starch—such as potato starch, tapioca starch, or cornstarch—to the minced meat in Chinese and Japanese dumplings. To understand this, I made six meatballs with minced pork and varying amounts of water, with and without cornstarch. The meatballs with the least water were denser and had more bite. On the other hand, more water meant that the patty was tender and pleasantly “spongy”. However, when added in excess, the patty can visibly “deflate” when steamed and disintegrate in the mouth without offering any bite. In all the meatballs where cornstarch is added, a velvety texture is produced, with the starch locking in the juices while reducing the “grainy” feel of cooked minced meat.

The vegetables

The combination of pork and cabbage is a common one in dumplings. Napa cabbage (also known as wombok or Chinese cabbage) or regular green cabbage can be used, but the goal is the same: to drive moisture from the cabbage while simultaneously softening it. Chopping green cabbage, salting it well, leaving it until it wilts, and wringing it dry seems to be the most common method. However, I found the texture of cabbage prepared this way distractingly crunchy in the resulting dumplings. I then tried boiling Napa cabbage leaves in salted water until they were tender, squeezing them to remove excess water, and chopping them finely. I much preferred this; Napa cabbage has a delicate sweetness that complements pork well and, when blanched, has a slightly juicy texture that is just delightful.

Wrapping the dumplings

I don’t mind making my own dumpling wrappers; from-scratch wrappers aren’t difficult to make and only require two ingredients—flour and water. (If you choose to go the store-bought route, however, look for the thinnest circular wrappers you can find as this promises the crispest, most delicate gyoza.)

There are two broad categories of dumpling wrappers: cold water dough and hot water dough. The former is best for boiled dumplings as the flour proteins form gluten in the presence of water, leading to chewier wrappers that can withstand turbulent boiling water without breaking. Hot water dough, known as scalded dough 烫面, is my preference for dumplings and happens to also be the traditional wrapper for gyoza. Hot water denatures the flour’s proteins, preventing gluten formation. Thus, the dough can be used immediately without resting and rolls out like a dream—this allows for thinner-skinned, delicate gyoza.

However, while hot water significantly inhibits gluten formation, it does not fully eliminate it. This is why the type of flour that you use—specifically its protein content—is crucial. Bread flour and all-purpose flour are both commonly used in dumpling wrapper recipes online. I’ve tried both and found hot water wrappers made with bread flour to be tough and chewy. In the Netherlands, where I live, flour is not labelled as “bread flour”, “all-purpose flour”, and “cake flour”. If that’s the case in your region too, you can simply check the protein content on the packaging; I’ve found flour with 10% protein to be ideal.

Pleats on the dumplings might seem fanciful, but they serve a function: allowing the gyoza to stand upright in the pan. This is particularly important if you’re frying them. I’ve been pleating dumplings the same way for years and am a creature of habit: fold the circle in half to form a half-moon, pinching the dough at the centre, then make three pleats towards the midpoint from each side. Made with this method, the prettiest dumplings are the ones with the pleats performed on a steep diagonal, thereby forming a graceful arc.

Cooking the gyoza

Raw gyoza do not keep well. Because the minced meat filling is so moist, raw dumplings that are left to sit will have their wrappers soaked through and end up misshapen or stuck to the parchment. While you can freeze the raw dumplings as a single layer before storing them in a container, frankly, who has the space?

What I think is sensible is to steam all of the gyoza until they are fully cooked. At this point, you can eat them immediately, pan-fry them in oil for a crisp base, or store them air-tight in the refrigerator or freezer for whenever the mood strikes. It’s important to steam the gyoza, evenly spaced apart, on baking paper or cabbage leaves to prevent sticking, tearing, and losing all the precious juices within.

Gyoza wings

To enjoy the crisp base that are the trademark of gyoza, you can simply fry the steamed dumplings in oil, but if you want to push the boat out, you can make what is known as hantsuki gyoza 羽根つき餃子 (literally “dumplings with wings”). This style of gyoza was invented in the 1980s by a restauranteur who poured a slurry of flour and water into the pan in an attempt to recreate the crispy-bottomed shēng jiān bāo 生煎包 that he tasted in his youth in China. When the water evaporated, the crisp lattice left in the pan stuck all of the dumplings in the pan together. A TV station that visited the restaurant in 1986 commented that the gyoza looked like they could fly, and the term hanestuki gyoza stuck.

Even though there’s only a handful of ingredients needed to make the slurry (mainly flour and water), gyoza wings can be very challenging to pull off. Usually, the pan is covered so the raw dumplings cook while the wings crisp simultaneously, but this can often lead to inconsistent results as the water in the pan may dry up before the dumplings are cooked through. The beauty of using pre-steamed dumplings is that you only need to worry about achieving a beautiful wing.

Success rests on multiple factors. First, the ratio of flour to water. Too little flour and the tuile resembles fine lace instead of a honeycomb structure (the addition of oil to the slurry also helps with the latter)—both styles are common but i prefer the look of the latter.

Ratios aside, four additional tips for success:

Using a pristine non-stick pan is paramount. If you’re using an old non-stick pan or a seasoned carbon steel pan, check that it is completely non-stick by frying an egg. If it is anything less than non-stick, fry multiple sunny-side eggs to create a non-stick seal—very simple but very effective. Eggs are magic!

Once the slurry is added, leave it to cook undisturbed until the water has evaporated and the tuile is beginning to brown. Shift the pan around the flame so that the tuile browns evenly.

When the tuile is golden brown, dab between the dumplings with paper towels to remove excess oil. Without this step, the oil would drip unappealingly onto your serving plate. If you dab at the tuile before it has browned, you risk damaging it (the tuile is very delicate before it browns).

Flip the pan while the dumplings and tuile are still hot. If the tuile is allowed to cool even slightly, it turns from slightly pliable to brittle and might not stay whole as you flip.

I’ve also experimented with a cornstarch, rather than flour, slurry. Cornstarch produces a crisp, brittle texture compared to flour, but is also more delicate and prone to breakage if you’re not careful. If presentation is important to you, go for flour! The wings may be a small detail, but they elevate the gyoza to a special treat. You’ll find the recipe to make the dumplings (including the wrappers from scratch) and the wings below ✨

🎄✨ With the gifting season upon us, support your favourite authors by purchasing their books! My second cookbook Plantasia was created in response to the growing meat-centric nature of modern diets. Instead of “veganising" traditional Asian meat and seafood dishes, Plantasia highlights the resourceful and ingenious ways Asia has celebrated plants for centuries, revealing the significance of ingredients like young jackfruit, gluten, and tempeh to Asian communities—long before these became trendy “meat substitutes”. As we approach Christmas, I’m offering a one-for-one deal to help you check off a few names on your gifting list. This applies to orders worldwide. If there’s a vegetable lover in your life or if you’re looking to incorporate more vegetables into your diet in 2025, now is the perfect time to get a copy of the book!

Gyoza

Makes 25 to 30 dumplings