✨ Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a newsletter dedicated to celebrating Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every Monday, you’ll be receiving a tasty mix of food history, stories, and recipes straight in your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. This newsletter is 100% reader-funded; each paid subscription supports the writing and research that goes into the newsletter, pays guest-writers, and gives you access to all content and recipes. Thank you for being here and enjoy this week’s post. ✨

Bite into an ensaymada — a fist-size buttery bread covered in a snowfall of grated cheese — and you instantly taste the paradox of a confection that effortlessly straddles the realms of bread and pastry, weightlessness and richness, sweetness and savouriness. Its history dates back to the 17th century on the island of Mallorca, part of the Balearic Islands in Spain, where it was originally known as “ensaïmada”. It is made by spreading a yeasted dough thinly on a bench, smearing it with lard, rolled it up swiss roll-style, and coiling the rope into a spiral. The pastries are then baked until they are flaky and well-bronzed, before being drowned in a thick cap of powdered sugar.

One origin story believes that the ensaïmada originated from the Jewish community in Mallorca. Jewish presence dates back to at least the second century, when the island was under both Muslim and Christian rule. However, with the onset of the Spanish Inquisition in 1478, many Jews was compelled to convert to Catholicism to avoid persecution. Despite this, some individuals were secretly practising Judaism and, to avoid suspicion, incorporated lard (the “saïm” in “ensaïmada”) — explicitly prohibited in Jewish dietary laws — into their pastries, a departure from the usual olive oil.

When the Spanish colonised the Philippines, the ensaïmada, along with other Spanish culinary traditions that were introduced, was adapted to local tastes and ingredients, becoming known as “ensaymada”. Unlike ensaïmada, ensaymada uses butter instead of lard and, while it is shaped similarly to the original, the fat is incorporated directly into the dough, rather than being laminated into it. This brings the flavour and texture of ensaymada closer to a brioche. In place of powdered sugar, Filipinos smear the tops of the buns with soft butter and sprinkle over sugar and grated cheese, thus creating a polarity of salty and sweet flavours that are not present in the original Spanish version. Over time, the Filipino ensaymada also evolved to accomodate local fillings such as ube and sweet mung bean paste.

The first time I tasted an ensaymada was after our helper came back from her holiday in the Philippines and brought me one from Goldilocks, a recognised bakeshop that has been operating since the 1960s. After a day or two of travel, it understandably wasn’t the softest or fluffiest, but it made me think about how ensaymada could be a canvas to showcase cheese. Now that I’m living in the Netherlands, there’s never been a better opportunity for me to make some ensaymada.

The process begins with a yeasted, eggy dough that starts off looking shaggy, but eventually becomes satiny, elastic, and smooth with a bit of elbow (or machine) grease. Although a stand-mixer is recommended, I find that you can get really good results by employing the slap-and-fold technique that was popularised by master baker Richard Bertinet. I compared recipes for ensaymada, ensaïmada, and brioche and found that ensaymada — while being less butter-rich compared to brioche — makes up for a lower % of butter with an abundant use of egg yolks, a quality that is widespread amongst Spanish-inspired breads and pastries. (Egg whites were historically used to clarify wines in Spain, and the yolks were donated to convents, where the nuns incorporated them into yolk-based sweets with a rich yellow colour.)

I wanted to make mine a little more special, so I snuck a sliver of bacon, along with a few knobs of soft cheese, into each. Once I pulled the pan from the oven, I immediately brushed the buns with soft butter — which gave them a remarkable sheen, but more practically, allows the toppings to stick — and sprinkled over sugar and grana padano. But even with the luxe add-ons, the star of the show was undoubtedly the shreddable, feathery crumb and the buns’ remarkable softness that allowed them to squish even between the gentlest fingers. I made a total of seven buns; today’s day three and the remaining buns still retain their tenderness though they’ve lost their sparkle a little, in the same way all leftover baked goods do. It is nothing that a minute in the microwave can’t fix, and in a way, the reheating even improves them: the cheese melts and melds with the sugar and butter on top, and the crumb, once again, regains its ethereal magic.

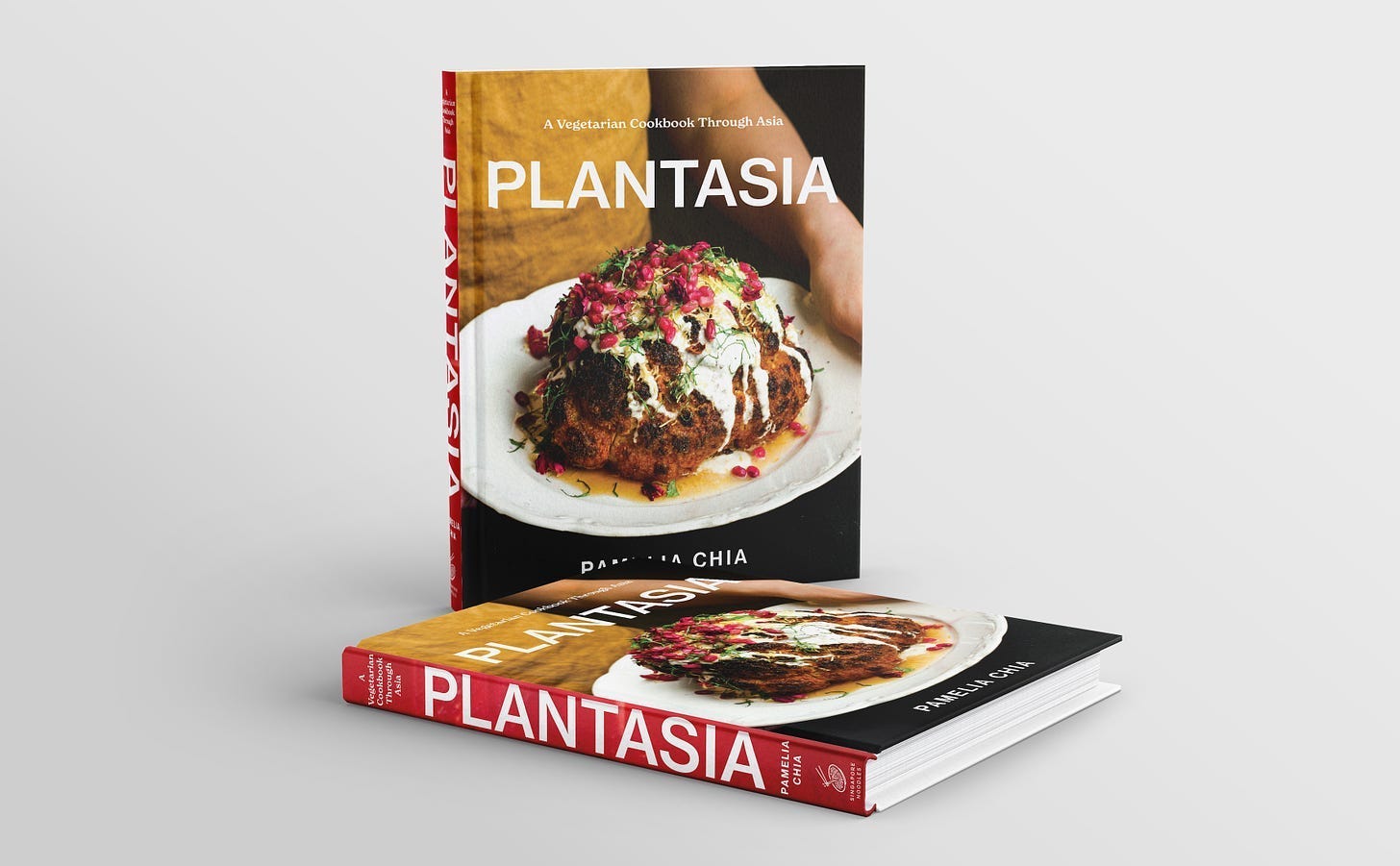

🥦 My second cookbook Plantasia: A Vegetarian Cookbook Through Asia leverages Asia’s techniques and flavour combinations to expand your repertoire of vegetable dishes deliciously beyond Western-style salads. Pick up your copy here or find a stockist near you. It is mostly vegan (or easily veganised), with plenty of allium-free options.

Ensaymada

Makes 7 buns