Doenjang jjigae 된장찌개

A vegetable-forward, soybean paste-powered stew that’s a staple in my weeknight rotation.

✨ Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a newsletter dedicated to celebrating Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every Monday, you’ll be receiving a tasty mix of food history, stories, and recipes straight in your inbox. You can also find archived recipes and other content in the index. This newsletter is 100% reader-funded—every paid subscription directly supports the writing and research, compensates guest contributors, and grants you access to all content and recipes.

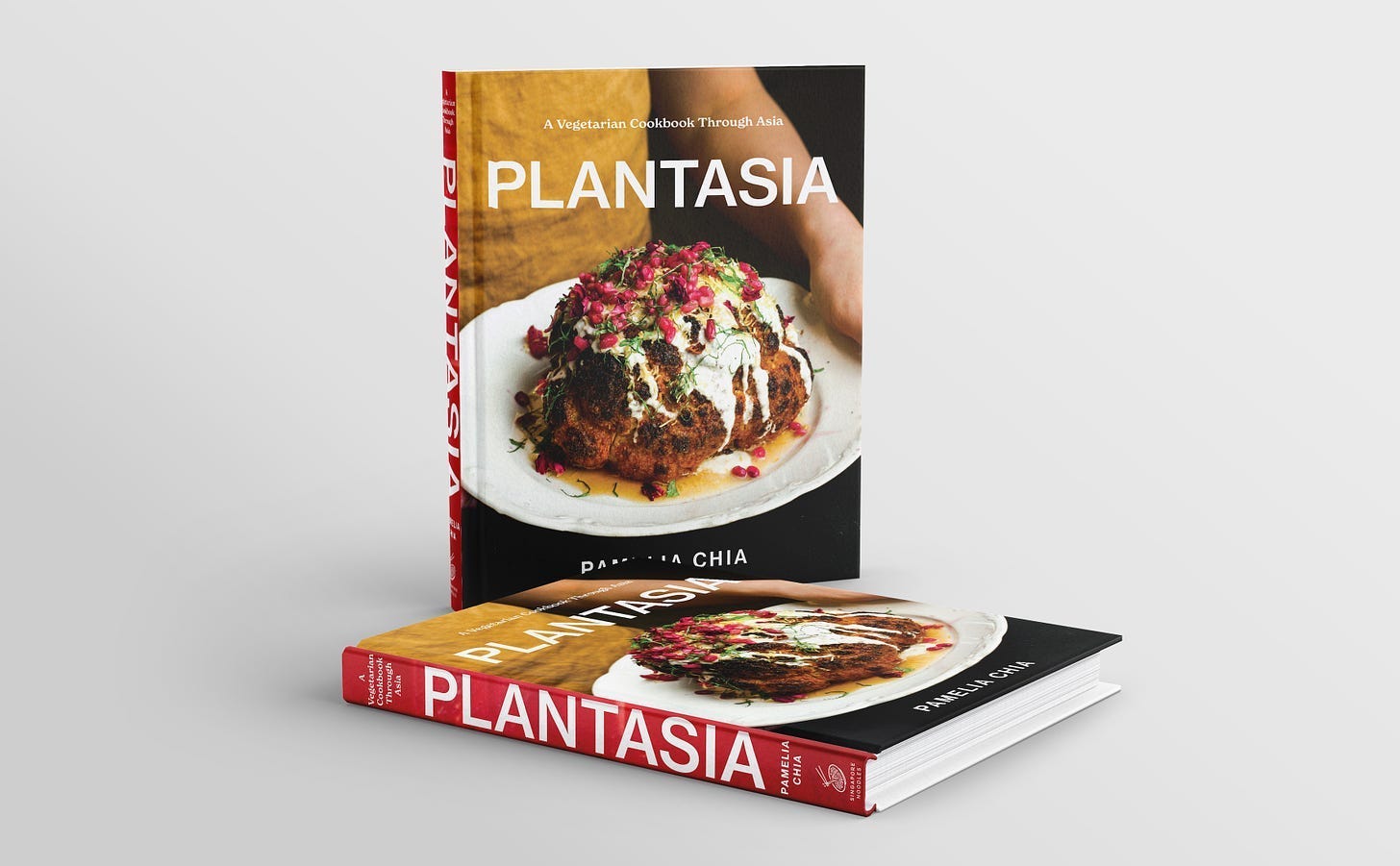

If you’re looking for Christmas gifts, my book Plantasia and an annual subscription to this newsletter would make fantastic options. In the lead-up to Christmas, I’m offering a one-for-one cookbook deal and 20% off all annual subscriptions. Thank you for being here and enjoy this week’s newsletter! - Pamelia✨

I always keep a container of doenjang, or Korean fermented soybean paste, in my refrigerator. As someone who grew up on a Cantonese mom’s and grandmother’s cooking, a meal without soup often feels incomplete. However, many Cantonese soups require hours of simmering to extract flavours from medicinal herbs and dried seafood—a time-consuming process that requires fore-thought and planning. These soups typically use a generous amount of meat, usually pork ribs, for flavour. As we now eat meat less frequently for environmental and health reasons, I reserve Cantonese soups for rare occasions when we really need the nourishment and instead prepare vegetable-forward soups with soybean paste as part of our weekly rotation of dishes.

One realisations that I had while writing my cookbook Plantasia was how important soybeans have historically been for many Asian cultures, particularly at times when meat was scarce. Although Korean cuisine is now widely recognised for dishes like Korean fried chicken and bo ssam, the traditional Korean diet was largely devoid of meat. During the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE - 668 CE), the spread of Buddhism led Koreans to adopt a more vegetarian diet, as Buddhist principles discourage meat consumption. Korea’s geography, characterised by mountainous terrain and limited flatlands, also made it inefficient to raise large numbers of livestock for meat production. Instead, the landscape was better suited for growing vegetables. In this predominantly agricultural society, live animals were valued more for their labour than for their meat. Consequently, the Korean people learnt to rely on plant sources for protein and flavour, with soybeans playing a crucial role in their diet.

Korea has three mother condiments, or jang 장, derived from soybean fermentation, which serve as the backbone of its cuisine: gochujang 고추장, a fiery red chilli paste; doenjang 된장, a thick fermented soybean paste; and ganjang 간장, a dark liquid similar to soy sauce.

To make doenjang, soybeans are harvested, boiled, and mashed into a paste. This paste is then molded into firm brown bricks and hung to air-cure. The blocks are subsequently submerged in salted water and allowed to ferment in large earthen vessels. After fermentation, the soybean blocks are removed from the vessels; the liquid remaining in the crock is ganjang, while the solids transform into doenjang.

Beyond imparting deep flavours, this traditional process is crucial for unlocking nutrients within soybeans. While soybeans are rich in high-quality protein, they also contain lectins and saponins that cause gastrointestinal distress, as well as protease inhibitors that prevent protein breakdown. However, boiling and fermenting soybeans destroys these anti-nutritional compounds and breaks down complex proteins, allowing for better absorption by the body.

Mingoo Kang, author of Jang: The Soul of Korean Cooking, notes, “For a citizenry that up until only about fifty years ago could ill afford meat and generally eschewed dairy, jang was a lifeline of protein, vitamins such as B12, fiber, and many other nutrients. Today, as the Western diet has seeped into Korean culture, jangs form an important health bulwark against the overconsumption of meat and its many accompanying maladies.”

Doenjang has similar counterparts in other Asian food cultures, such as Japanese miso, which is mild and slightly sweet in flavour; and taucheo (also known as tauco), a fermented soybean paste integral to various Southeast Asian cuisines, particularly in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand. While doenjang has the thick paste-like consistency of miso, its intense earthiness and wild funkiness are more reminiscent of taucheo.

Doenjang serves as a backdrop flavour in many Korean dishes and sauces—such as ssamjang, a popular condiment for meat and lettuce wraps—but it truly shines in doenjang jjigae 된장찌개, a stew that is closer to a broth in consistency.

In my doenjang jjigae, I use dried anchovy stock as the base—a common choice in many versions of the dish. To make the stock, Korean cooks tend typically simmer large anchovies (with their heads and guts discarded) in water to infuse their flavour before discarding them; they are not eaten. However, having grown up in Singapore, where we are accustomed to smaller dried anchovies that we call ikan bilis, I take a different approach. These require no prep work and are delicious enough to eat whole. The key is to lightly fry the dried anchovies in oil until they just turn translucent and slightly golden; if they become crispy, they won’t release their flavour into the broth. Add water to the pot and boil aggressively for 15-20 minutes; dried anchovies shouldn’t be boiled for too long or they may turn bitter.

Another technique that has transformed my approach to making doenjang jjigae is briefly frying the paste before adding water. This step caramelises the doenjang, allowing its fragrance to bloom and awaken.

Ingredients that go into this fermented soybean paste stew can vary widely: Sohui Kim describes it in her cookbook Korean Home Cooking as a “soothing bowl of silky potatoes, soft tofu, and sweet squash stewed with the nutty Korean soybean paste”, while Deuki Hong and Matt Rodbard of Koreaworld consider it a “foundational recipe” that combines “earthy doenjang, tofu, squash, clams, and beef”. Below you’ll find my recipe for doenjang jjigae, which includes a bit of pork, zucchini, and tofu. However, the beauty of this dish lies in its versatility; as long as doenjang is the star, you can adapt it to what you have on hand in your refrigerator. Sometimes, I even drop eggs into the stew.

Homemade kimchi and some crisp sheets of seaweed, along with short-grain rice (I cook mine with millet and canned kidney beans), pair deliciously with this.

🥦 Are you looking to incorporate more vegetables into your everyday meals? Whether you're a vegetarian, vegan, or omnivore, Plantasia will inspire you to embrace the potential of vegetables in exciting and satisfying ways. It has 88 recipes that are mostly vegan (or easily veganised) and plenty of allium-free options, with insights from 24 chefs and food writers from across Asia, making it a rich resource for anyone looking to elevate their vegetable cooking. In the lead-up to Christmas, I’m offering a one-for-one cookbook deal. Pick up your copy here!

Doenjang Jjigae 된장찌개

Makes 3 servings