My cookbook ‘Plantasia: A Vegetarian Cookbook Through Asia’ will be out in ONE month! The motivation to write this book came when I moved to Melbourne in 2019, a year of severe bushfires. Learning about how meat is a big contributing factor to climate change, I resolved to cut down on my meat consumption and sought out pleasurable ways to sustain this change.

This book is the culmination of my journey, one that reconciles my Asian palate and heritage with a desire to eat more vegetables. My mission is not to convert anyone to vegetarianism, but to change people’s perceptions of vegetables as being boring or unpleasant, so that they would be willing to introduce more greens to their plates.

In the book, you’ll find recipes for 88 vegetable-forward dishes that promise to be as dynamic and satisfying as dishes made with meat, as well as 24 interviews with cooks inspired by Asia’s vegetable wisdom. Preorder here (worldwide shipping available).

Chicken Rice

Like many Singaporeans, I never felt a need to cook hawker dishes when I lived in Singapore. Wherever on the island you are, there would be at least one nearby hawker centre that serves up delicious, quickly whipped up plates of food for a few dollars, so why bother? When I first moved to Australia, however, I hesitated to cook hawker dishes for a different reason - hawkers spend decades of their lives perfecting one dish, how can I possibly top that experience at home?

It was cooking professionally in Melbourne that gave me the figurative kick in the butt to learn. I felt like an imposter every time a chef asked me to cook something “from home” for staff meal - I often looked up recipes the night before and winged it on the day. Once, there was a very specific request for chicken rice from my chef who told me that he cooked the dish frequently for his son, but wanted to taste a version prepared by a Singaporean. It put me to shame that a white chef in Australia was more experienced at cooking chicken rice than I, a born and bred Singaporean, was.

While I managed to produce a respectable version of the dish for staff meal, I knew that it was far from perfect. There is no lack of chicken rice recipes on the net or in local cookbooks, but they often aren’t authentic to the Singaporean hawker version that I grew up eating. Usually you can tell even before cooking. Some lack the all-important dressing that is ladled over the poached chicken. Other times, the chilli sauce might call for sambal or *gasp* sriracha. The horror! And almost always, the chicken and the rice cooked according to these recipes would taste blander than what I had hoped for.

It took a couple of years of cooking meal after meal of chicken rice that I came to a version that I was satisfied with. But still, it is a never-ending quest for chicken rice perfection. Recently, we moved from Australia to the Netherlands and were amazed by the quality of chicken available in supermarkets. Like kampung chicken, Dutch chickens have yellow-tinged skin and such a fatty quality that stripping the skin off the flesh would would leave an oily sheen on my hands. Wex said, “You should really try making chicken rice with this.” I concurred and, after coming home from Portugal and craving for comfort food, it felt like the right time to.

Origins of chicken rice

It turns out that the chicken rice that we enjoy in Singapore evolved from two separate Hainanese dishes: Wenchang chicken and chicken rice balls. Wenchang chicken is a breed of chicken on Hainan island that, according to Johor Kaki, is allowed to roam free before being kept in coops and fed rice husks, peanut, sweet potato and grated coconut flesh. The result is an exceptionally fatty and yellow-skinned bird. Because Wenchang chicken tastes so spectacular on its own, it is poached or steamed to bring its natural flavour to the fore, with no superfluous seasoning that might distract.

Chicken rice balls are a separate dish altogether, that the Hainanese prepare during festive occasions as ancestral offerings. The rice would be cooked with an aromatic garlic paste, rendered chicken fat (essentially schmaltz) and chicken stock, such that each grain would be thoroughly infused with the essence of chicken. The cooked rice is then formed into large round balls as a symbol of family togetherness (圆满, literally ‘round and full’). The dish would be served first to the ancestors, before the living members of the family tuck in - a shared meal that transcends death.

Following the opening of Hainan island to seafaring activities and foreign trade in 1870, many Hainanese left their shores for Singapore, bringing along their traditions with them. One of these men, Wong Yi Guan, eked a living for himself by slinging cooked chicken and chicken rice balls on his shoulders, and selling the combined components as a meal on the streets. He became the very first chicken rice seller in Singapore, and other Hainanese hawkers soon followed suit, offering customers a choice of fluffy chicken rice or compacted rice balls to go with the chicken.

It was not long before the Cantonese, also immigrants in Singapore, began hawking the dish. Their contribution to chicken rice lies in the technique of plunging the poultry into boiling liquid, turning off the heat, and allowing it to poach gently in the residual heat. By the time the liquid reaches room temperature, the flesh would have be just-cooked and more delicate and silky than the original Hainanese version. Dunking the bird in icewater was another Cantonese touch, a technique that adds springiness to the skin, a quality prized by the Cantonese.

Because cooks in Singapore had access to pandan and lemongrass, these aromatics have made their way into the dish. Plates of chicken rice also began to be accompanied by saucers of chilli sauce to appeal to the locals’ penchant for spice.

The stock

The value proposition of many chicken rice recipes goes like this: you poach the chicken in sufficient water to cover it, producing an instant chicken stock with which you cook the rice. Efficient and brilliant! Some hawkers practise this, but try it at home and you get bland chicken and a broth that lacks oomph.

The difference lies in the fact that when hawkers do it, they tend to fill the pot with dozens of chicken (see 2:50 of this video). When you do it at home, however, with a single chicken submerged in a pot of water, the flavour is much weaker. To get around this, Hainanese cookbook author and TV host Adam Liaw recommends cooking two whole chickens instead of one for “extra savouriness”. But here’s the thing: if we are barely poaching the chicken until it is just done, how can we guarantee that the water would turn into a flavourful broth by the end of cooking?

My solution: use homemade chicken stock instead of water to poach your chicken. It turns out that this is an additional step that some hawkers do (see 3:00 of this video). I previously favoured chicken carcasses for preparing the stock, but now I use chicken legs so I can easily strip off the skin for fat to cook the rice with.

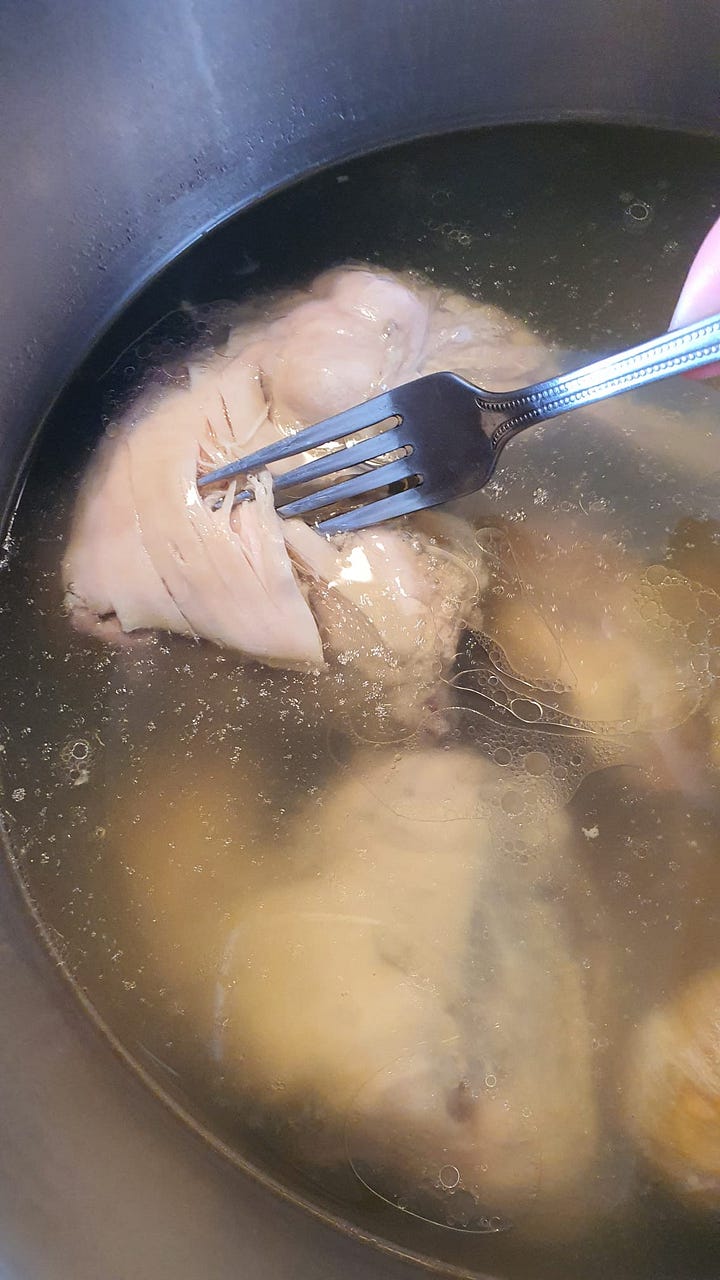

Poaching the chicken

Another tip that Adam Liaw dispenses in his video is to season the poaching liquid well. It makes sense to season the chicken as it cooks, and that was what I once did, but no longer do. Here’s why: usually at a Singaporean hawker centre, you are served a light broth of chicken stock for slurping in between bites of chicken rice. In order for the chicken to be properly seasoned, you would have to season the poaching liquid rather aggressively, causing the resulting broth to be too salty to enjoy as soup.

Instead, here’s what I do: before poaching, I rub the chicken all over with coarse salt and allow it to sit for 1.5-2 hours before rinsing. This serves three purposes.

It exfoliates the skin, producing a smoother texture.

Rubbing with salt and rinsing ‘cleans’ the meat effectively. My mom and two grandmothers do it all the time with any animal protein they cook. This is especially crucial in a dish like chicken rice, where the chicken has nothing to hide behind. You’ll want to rid the chicken of any impurities and unpleasant odours such as that of blood before cooking.

Allowing the bird to sit in the salt allows the seasoning to penetrate the bird and keeps it juicy when cooked, like a dry-brine of sorts.

To lower the chicken into the pot, hawkers either grip the chickens by their neck with their bare hands, or use strings or some kind of S hook-contraption. The chickens are plunged in and out of their hot bath, like tea bag in a cup of tea; the flow of hot liquid in and out of the cavities allows the birds to heat up evenly. The struggle for the home cook who lives outside of Asia lies in that it is close to impossible to find chickens with their necks on! You could use something like a kitchen spider to dunk your neckless chickens in and out of the pot, but it is messy and you run the risk of ripping the skin in the process.

The lightbulb moment came when a follower on Instagram gave me a tip she picked up from a Hainanese neighbour: instead of allowing the chicken to cook in the residual heat of boiling water, why not heat the chicken in room temperature water without letting the liquid boil instead? It works like a treat. I don’t have to worry about uneven cooking and the chicken is silky every time. I have not looked back since.

For easy removal from the pot, I tie a piece of twine around the ankles of the chicken and once cooked, I dunk it in well-seasoned ice water (a wonderful tip I picked up from Adam Liaw). If your chicken skin is not ripped and if you use a generous enough amount of ice, what happens is that the gelatin-rich juices under the chicken skin instantly set into aspic before they are able to escape. Very few chicken rice hawkers bother to use enough ice (Leslie Tay wrote about a dedicated young hawker who invested in an ice machine just for this purpose), so it is a real treat when you find a layer of jellied chicken essence under the skin.

The rice

Now, what you’re left with in the pot is liquid that is packed full of flavour from the stock-making and the chicken-poaching. This is half the battle won, because this stock is what goes into every component of chicken rice: the soup, rice, dressing and chilli sauce. It’s simple: a weak stock = substandard chicken rice.

But a good broth is not the only thing that makes good chicken rice. Chicken rice connoisseurs know that good chicken rice is all about the chicken fat. Any chicken rice hawker worth his or her salt would render chicken fat (see 1:00 of this video) and use the rich yellow oil to fry the aromatics for the rice. Typically, you would use the fat deposit collected from the cavity of the chicken, but I’ve noticed that not all birds come with a generous flap of fat. So, I make up for it by rendering skin from the chicken legs that I use to prepare the stock as well.

I cook my chicken rice with pandan and lemongrass, on top of the mandatory ginger-garlic paste. The pandan is an obvious must-have for any chicken rice recipe, but the lemongrass is more contentious. I began adding it to my homemade chicken rice after noticing stalks of it sticking out of the rice pot at a chicken rice stall I love. You wouldn’t necessarily identify the lemongrass as you’re eating the chicken rice, but it rounds out all the flavours.

Made with sufficient fat (particularly from a yellow-skinned bird) and a proper stock, chicken rice is almost yellowish in hue and practically glistens. Beautiful, hypnotic stuff.

I never feel more Singaporean than when I cook and eat chicken rice at home. It’s just one of those dishes that’s so pivotal to our national identity that I believe it should be made essential learning in home economics classes.

For an overseas Singaporean, there’s almost nothing better than being invited into a fellow Singaporean’s home for homemade chicken rice. That happened to us once when we were living in Australia and we almost wept at the sheer familiarity and comfort of it. The good thing is that the core ingredients for chicken rice are readily accessible everywhere, so you can recreate a little slice of home wherever in the world you may be.

So how did the Dutch chickens fare in chicken rice? I think it was the best chicken rice I’ve ever made in my life. Wex was full of praise - he ate three platefuls for dinner, and then another for supper. “You’ve outdone yourself.” “10/10!” “Perfect chicken, perfect rice.” “Wow, the person who invented chicken rice really knew what he was doing.” (If you know anything about Wex, this is extremely uncommon behaviour because he believes that there’s no such thing as perfection and rarely gives anything that I cook a solid 10/10 😂)

All I can say is that chicken rice is the ultimate showcase for quality chicken and, as strange and counter-intuitive as this might sound, if you have great chicken, don’t roast it - poach it! If you live in the Netherlands, France, Hong Kong or anywhere else in the world where you can source amazing chickens, make chicken rice - you’d be doing yourself a disservice not to. But even if you can’t find yellow-skinned, fatty, flavourful poultry, the dish is so great that even ordinary chooks would do.

Recipe in Part II! 💚