✨ Welcome to my newsletter, Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every Monday, you’ll be receiving historical tidbits, personal stories, and recipes delivered straight to your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. This newsletter is 100% reader funded; each paid subscription supports the writing and research that goes into the newsletter, pays guest-writers, and gives you access to all content and recipes. Thank you for being here and enjoy this week’s post. ✨

What I miss about living in Melbourne is the affordable and amazing Vietnamese eateries that we had access to. We ate exceptional pho on a regular basis — Wex’s go-to was beef pho (phở bò), and mine was chicken pho (phở gà). I’ve never thought of making beef pho at home as beef can be pricey, and extracting their flavour can be a lengthy process, akin to making ramen broth. One of Wex’s aunts used to own Vietnamese restaurants in Singapore and, working there as a student, he was privy to how the dishes were made. According to him, the broth for beef pho required a low-and-slow simmer overnight. In a domestic setting and with soaring gas prices, doing so for only two people is a thought simply not worth entertaining. Chicken pho, on the other hand, takes less time and is way more economical. That’s not to say that it doesn’t require attention. To make it involves the same level of vigilance, but it’s worth it when all that skimming and layering of flavours produces a broth that is simultaneously clear yet deep, light yet savoury.

According to Andrea Nguyen’s The Pho Cookbook, chicken pho made its appearance in Vietnam in the 1930s, when the government forbade butcher shops from selling beef twice a week. The popular explanation is that cows and buffalos were the main means of ploughing fields before machinery was used, which meant that their slaughtering had to be controlled. Restaurants worked around the absence of beef on those days by offering pho made with a more accessible source of meat: chicken. The public was initially against this, to the point of boycotting the new pho, as they felt that it couldn’t compare to the deep savouriness of traditional beef counterpart. However, with time, as cooks learnt to calibrate seasonings that suited the distinguished taste of chicken, the dish grew in popularity.

The meat

The Vietnamese are fastidious about selecting chicken for pho, and rightly so. This is a dish where the chicken is the star and the preparation so delicate that there’s nothing to hide behind. Free range chickens are best. In Vietnam, these are known as Gà Đi Bộ, meaning ‘walking chicken’. Because of the chickens’ free-roaming diets, the skins are characteristically yellow-tinged. In the absence of quality chicken, it is not uncommon for Vietnamese cooks to rub the chicken’s skin with turmeric-infused oil after it is poached to replicate the look.

The chicken does double duty in this dish — it flavours the broth and is served as the star component. Many traditional recipes call for a whole chicken to be cooked until tender and dunked into an ice bath so that the cooked flesh can be picked off, and the carcass can be returned to the pot. This ensures that the shredded chicken that tops the noodles would be perfectly à point, while the bones give up as much flavour as they have to offer. Cooks who are dextrous with a knife debone the entire chook before adding both the carcass and flesh to the pot; this allows the flesh to be easily retrieved once it is done cooking. I prefer a less fussy method: I simmer a small whole chicken to make the broth and then cook boneless chicken thighs for topping.

To bolster the chicken flavour, using MSG or some kind of chicken bouillon is the norm rather than the exception in Vietnamese homes and restaurants. I chose to skip this (though Wex did tell me that it isn’t the same without MSG). Instead, I added a measure of pork to the broth for savoury depth.

Achieving a clear broth

Clarity — both in appearance and flavour — is the number one virtue of any pho. A Redditor explains this as tasting “organised and not messy”. There are a few ways to achieve this:

Scrubbing the meat and bones with coarse sea salt to remove impurities.

Soaking the meat and bones in cold water to draw out the blood. This is more crucial for beef pho to reduce the gaminess of beef.

Blanching the meat and bones to pull out blood and scum that turn the broth cloudy. Look at the photo above: the liquid in the pot was leftover from blanching the meat / bones — all that gunk!

Adding a peeled onion or a length of daikon (author of Little Viet Kitchen Thuy Pham-Kelly uses daikon in her chicken pho) helps to clarify the broth as it cooks.

Constant, patient skimming of scum and oil from the broth.

Straining the stock, preferably through cheesecloth.

Refrigerating the broth overnight and skimming off the fat that has congealed.

Flavouring the broth

What separates chicken pho from your run-of-the-mill chicken broth are its flavourings, which are added in the final stage of cooking:

Charred aromatics — Onions and ginger are typically charred over an open flame in their skins (a broiler can also be used). They are ready when they have softened, the skins are blackened, and juice emerges from the onions. Be thorough in washing off the char as this will cause your broth to turn dark. Only 30 minutes is required for their flavours to be fully extracted; any longer and they may make your soup bitter.

Spices — While beef pho emphasises a stint of intense roasting for the bones and the use of robust spices to stand up to the strong beefiness, subtlety is the name of the game with chicken pho. Bulbs and roots are used to bring freshness and sweetness to the soup and the spices are used sparingly so that the natural flavour of the chicken shines through.

Fish sauce — Fish sauce should be added only towards the end as its flavour changes after a long cook. It should be used sparingly as, while it adds umami, too much distracts from the chicken flavour.

Noodles

The noodles are such a big part of the pho experience that the flat rice noodles themselves are named after the dish (bánh phở). Purists would insist that only fresh noodles should be used — these are typically available at Asian markets or Asian grocers under their refrigerated section. If you live in a country with a sizable Southeast Asian population, this would be easy to source. If you’re using fresh refrigerated noodles, soak them in boiling water for 30 seconds to loosen them before draining and adding them to your broth.

For those like me for whom fresh noodles are impossible to source, there’s technique in cooking the dried noodles properly. Cooking them directly in the broth is a huge no-no because the starch will leach into your broth and ruin the flavour. Instead, do this:

Pre-soak your dried rice noodles in cold water for 10 minutes, or until they are pliable. This eliminates excess starch that might render the noodles sticky when they are cooked. Drain, and set them aside until your pho is ready to be assembled.

Boil the drained noodles in salted water until they are almost done, or are tender but still al dente. Stir the noodles in the boiling water with chopsticks (not tongs to avoid breakage) as they cook so that they separate into individual strands.

Drain the boiled noodles and rinse them in cold water. This halts the cooking and avoids mushiness in the noodles.

Allow the noodles to sit in the colander for 5 minutes. Adding sopping wet noodles to your broth is a surefire way to dilute the flavourful broth that you worked so hard to achieve.

Assemble your pho. Divide your noodles between serving bowls and top with the sliced or shredded chicken, herbs and other garnishes. Finally, ladle over the hot broth, which will finish the noodles to the right doneness.

We enjoyed our chicken pho with lots of fresh herbs from the garden, bean sprouts, and a zingy lime leaf and black pepper dipping sauce on the side and it was such a wonderful thing to eat on a warm day.

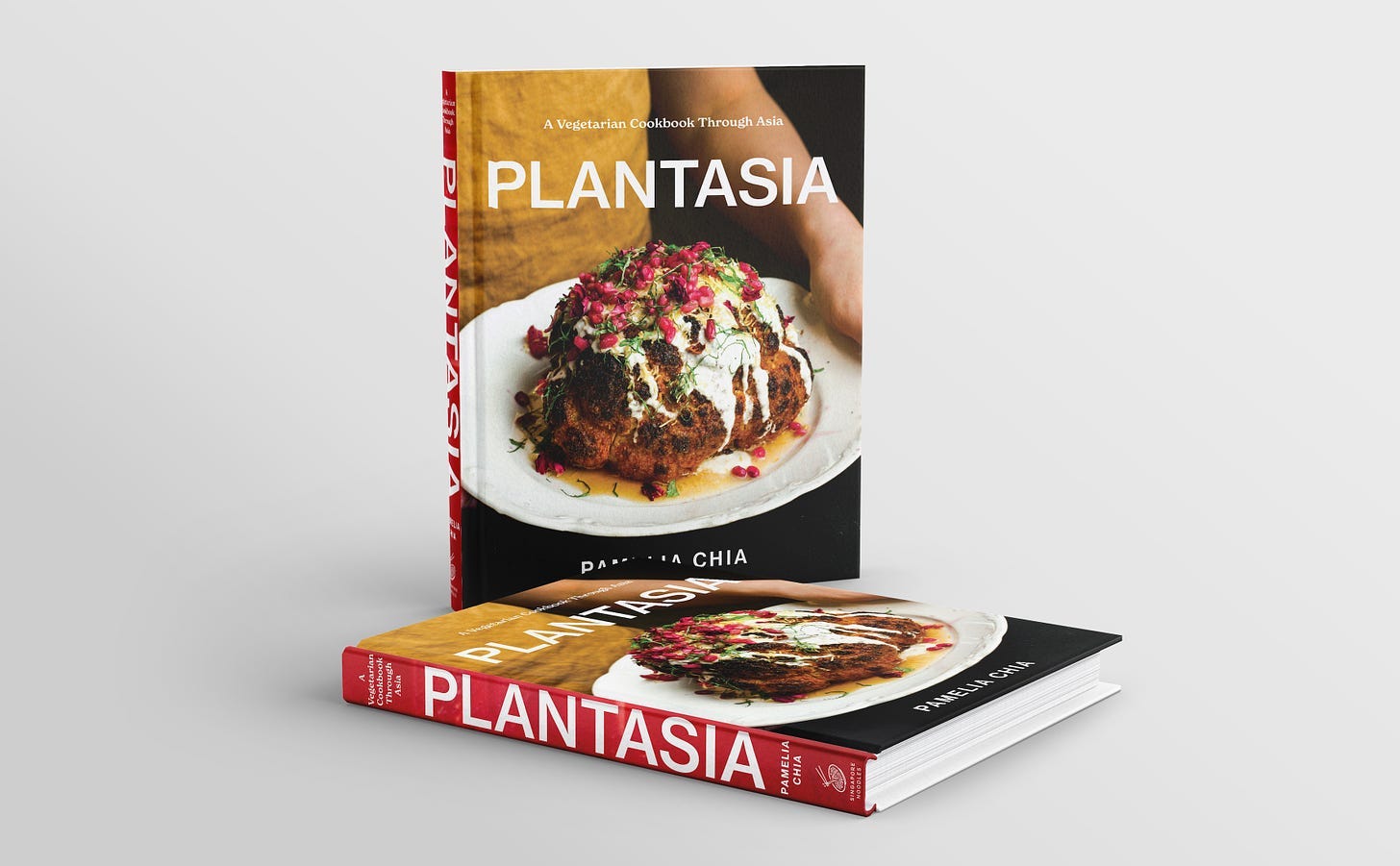

🥦 My second cookbook Plantasia: A Vegetarian Cookbook Through Asia leverages Asia’s techniques and flavour combinations to expand your repertoire of vegetable dishes deliciously beyond Western-style salads. Pick up your copy here or check out the list of international stockists here. It is mostly vegan (or easily veganised), with plenty of allium-free options.

Chicken Pho (Phở Gà)

MAKES 4 SERVINGS