✨ Welcome to my newsletter, Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every Monday, you’ll be receiving historical tidbits, personal stories, and recipes delivered straight to your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. This newsletter is 100% reader funded; each paid subscription supports the writing and research that goes into the newsletter, pays guest-writers, and gives you access to all content and recipes. Thank you for being here and enjoy this week’s post. ✨

Whenever the weather heats up, I start craving pickles and ferments — anything acidic to whet the appetite and dispel lethargy. When we were living in Melbourne, our Korean friends introduced us to the wonders of Korean supermarkets and the affordability of large containers of kimchi in the 5-10 kilograms range. Now, living in the Netherlands, I balk at the price of the small containers at the Asian supermarket, sometimes prohibitively expensive to purchase apart from a rare treat. Naturally, I’m compelled to make some at home. Given kimchi’s global appeal and widespread popularity, there is certainly no lack of recipes online, but what I desperately wanted was to make it right. How to avoid an overpoweringly salty kimchi? Is the amount of liquid in my jar sufficient? Will my kimchi go bad?

There’s a tremendous amount of misinformation online and, as I pored through Reddit forums, I realised that few posters were actually making anything that resembled what I’d get at Korean restaurants, where the wombok is attached to the stem in long strips and snipped to order with scissors. In fact, the ones that I’ve seen tend to look incredibly watery, almost like a chilli-flecked sauerkraut more than anything. Recipes online also tend to work in extremely large quantities (multiple heads of wombok), which puts me off making the ferment since my fridge space is precious and it’s just us two at home. While there are many types of kimchi enjoyed in Korea, this newsletter focuses on baechu kimchi 배추김치, or wombok kimchi, which is probably what most non-Koreans think of when they contemplate kimchi.

Cutting the cabbage

There are two styles of baechu kimchi, depending on the way the wombok is cut: mak kimchi 막김치, where the wombok is chopped up into bite size pieces; and tong baechu kimchi 통배추김치, where the wombok is left in halves. Mak kimchi makes sense from a convenience standpoint: it can be a hassle to retrieve the kimchi from the jar and cut what you need each time you have a craving. However, tong baechu kimchi is time-honoured for a reason — the large pieces of vegetable allow fermentation to occur at a leisurely pace, which means that it can be stored longer without turning overly sour or aged. Tong baechu kimchi is, thus, a particularly good option if you’re making big batches of kimchi. Rather than cutting the wombok in two with a knife, cooks make a deep incision at the bottom end of the wombok, then pull the two halves apart to produce a beautifully ruffled, natural look.

Salting

How you cut or halve your wombok is secondary. What is crucial is the salting process. Some even say that salt is the most important in making kimchi. Salt achieves three goals in kimchi.

It renders the wombok pliable so that the individual leaves can be peeled back and be coated in the seasonings.

It inhibits the proliferation of bad bacteria, allowing the good bacteria that are responsible for lacto-fermentation to grow.

It draws water out of the wombok, so that the texture of the cabbage becomes pickle-like and crunchy.

While most of us view salt as the most elemental and basic member of our pantry, it is an ingredient with a lot of nuance to Koreans. In general, high-quality sea salt is vastly preferred over table salt. Some of the reasons for this are seasoned with superstition; some say that table salt would turn kimchi bitter, while others claim that the iodine present negatively impacts desirable bacteria, causing bad bacteria to take over. (A study conducted on sauerkraut has since debunked this popular belief.) Having coarse sea salt on hand is key - the large crystals are said to be superior in penetrating the tough wombok stems, which can be “impervious to even the largest quantities of table salt”.

Recipes online are split in the ways to salt wombok for kimchi. Some soak the kimchi overnight in salted water, while others sprinkle coarse salt all over the cabbage. I’ve also been introduced to the brine method from Korean friends, who tell me about how dipping the wombok in salted water helps the coarse sea salt to adhere better. One Redditor who professes experience in preparing 30 pounds of kimchi at a time offered a hybrid method: she dips the wombok in salted water to wet the leaves, adds coarse salt between the layers, then submerges the wombok in brine. Ultimately, the key is not so much about adopting any specific method, as long as the salting is adequate and thorough. By the end of the salting, the wombok’s crunchy stems should be able to withstand being folded in half without snapping.

Rinsing and draining

Because so much salt has gone into the wombok, it is paramount to rinse it well. The idea is to reach a happy medium: not enough salt will cause the cabbage to spoil, but too much salt will produce an inedibly salty kimchi. Taste both the stem and the leaves after rinsing — you should be able to taste the natural sweetness of the stem through the salt. The leafy pieces should taste too salty, but not so much that you feel like you just ate a spoonful of salt. Ultimately, because there’s wild variation in how much salt washes away in the rinsing process, precise measurements of salt and exact times on how long to rinse are arbitrary and irrelevant. Always rely on your own sense of taste. Once the wombok is at a salinity that you’re pleased with, remove as much water from it as you can by squeezing it with your hands, then patiently allowing it to drain in a colander. Skipping this step or performing this poorly will result in kimchi that is overly watery or salty.

Seasoning paste

Unlike ferments and pickles from the West that emphasise the submergence of vegetables in brine, kimchi is unique in that the vegetables are coated in a strong-tasting paste. Here are the main components of this paste:

Gochugaru 고추가루 — Essentially ground dried chillies, gochugaru accounts for the redness that we associate with baechu kimchi. There are two types: coarsely ground and finely powdered. Go for the coarse flakes as the powder separates easily to the bottom and forms a thick red sludge on the bottom of your jar. Can you use other chilli flakes? You can, but gochugaru has the benefit of simultaneously being intensely red and exceptionally mild. If you use other chilli flakes in the same quantities, you might end up with inedibly fiery kimchi. I’ve also seen some cookbook recipes for the paste being made with red capsicum to enhance the colour of the kimchi without using as much gochugaru, though this hardly seems traditional.

Umami — Umami is introduced to the seasoning paste in several ways: notably in the form of seafood, such as salted shrimp (saeu-jeot 새우젓), fish sauce, and/or raw oysters. Modern recipes add MSG. But this doesn’t mean that you can’t make a stellar kimchi if you’re vegetarian or vegan — you can use soy sauce and/or other fermented soy products instead, plus the rice slurry offers up another avenue to add umami (see below).

Rice slurry — This was a game-changer in my journey of making kimchi. It’s what turns your seasoning paste from a watery brine to a viscous, slightly thickened paste that coats every leaf. In an Eater video, Kwang Hee “Mama” Park, dubbed “Master of Kimchi”, uses a homemade stock of dried shiitake mushrooms, kombu, sand dried anchovies. Jihee Shin, an Australia-based kimchi maker whom I featured in Plantasia, makes a stock of kombu, shiitake mushrooms, and vegetables for her vegan kimchi, and finds it especially crucial in imparting umami. Making your own stock is feasible for large quantities of kimchi, but for one head of kimchi, where only about a cup of rice slurry is needed, it is rather impractical. For this reason, I use instant dashi (an ingredient I always have in my pantry) and love the oceanic depth that it adds to the kimchi.

Sweetness — Sugar jumpstarts the fermentation process and balances out the seasoning of the kimchi. Eric Kim’s kimchi recipe in Korean American uses maesil-cheong 매실청 (plum extract) that I’m very fond of but is not widely accessible. Traditional kimchi recipes feature pureed fruit, such as Asian pear, that adds natural sweetness and body to the seasoning paste. Being an applesauce lover, I added some to my kimchi and it turned out to be the unexpected MVP.

Vegetables — An assortment of vegetables, in addition to the wombok, are used in baechu kimchi. They provide a fresh, crunchy foil and add pungency. The most common ones are garlic chives, spring onion, nashi pear, and daikon, but there are also recipes that call for carrot and apple.

Fermentation and enjoying your kimchi

A prevalent kimchi myth that needs to die is that it should be left out on your kitchen counter to ferment for a long time. This is simply not a practice in Korea. If there’s one thing that I’ve taken away from learning about kimchi, it is that Koreans enjoy baechu kimchi at all stages of its development; it does not have to be funkadelic all the time. Unlike other ferments, where the vegetable is only considered ready to eat when it is considerably aged, kimchi can be enjoyed as soon as it is tossed together.

When baechu kimchi is freshly made, the seasoning hasn’t yet penetrated the leaves and hence acts as a sort of salad dressing. It is enjoyed raw, usually with boiled pork wrapped in lettuce leaves (bossam 보쌈). I first heard about the idea of eating “fresh” kimchi from Jihee, who tells me of her preference for fresh kimchi and her tendencies to sell her kimchi while it is quite young, to be eaten as is. As the kimchi ages, it gets progressively sour and funky. With such kimchi, “the best way to enjoy it is cooked in kimchi pancake or in a stew.”

I store my kimchi in the refrigerator in the fridge immediately after making it, and find that Day 2 kimchi is remarkable. It still tastes fresh, but the overnight’s rest has developed the flavours and allowed the seasonings to penetrate the cabbage. However, if you’d like to jumpstart the fermentation and get it to the ripe, acidic peak quickly, leave the kimchi on the counter for no longer than a day or two at cool room temperature before placing it in the refrigerator, where it will continue to ferment slowly. A few notes about kimchi fermentation:

Does kimchi require oxygen? No, kimchi fermentation is anaerobic, meaning that it does not require oxygen to take place. As oxygen can cause bad bacteria to take over the fermentation, do make sure that there is no more than 2 inches of headroom in the container. That said, because the kimchi produces carbon dioxide as it ferments, make sure that the containers are not packed to the brim.

Does kimchi require warmth? / Should it only be made in summer? No, because you can enjoy baechu kimchi fresh, without fermentation. In any case, baechu kimchi is traditionally made after the wombok harvest in autumn. The seasoned cabbage would be packed into clay pots and stored underground during winter.

Does kimchi require light? No, when fermenting at room temperature, store your kimchi in a dark cupboard or away from direct sunlight.

Baechu kimchi is truly a wonderful thing to have in your fridge. It keeps for weeks, if not months, and is an instant vegetable side dish whenever you’re too lazy to whip up much for dinner. It’s also great for dipping into throughout the day, to have on its own or with rice, whenever you’re feeling peckish. The recipe that I provide below makes 1 wombok’s worth of kimchi, which will last two people 2 to 3 weeks 🩷

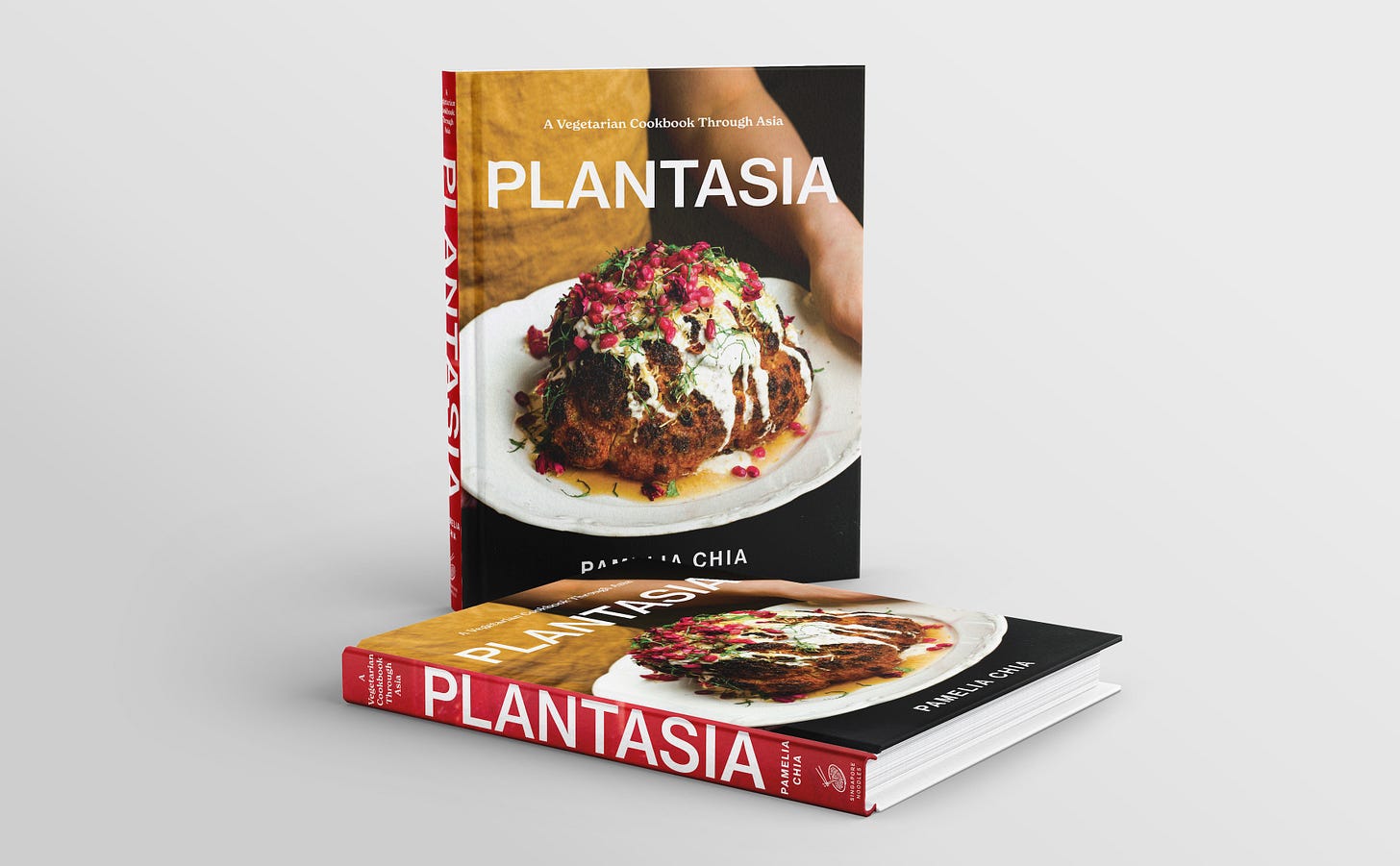

🥦 My second cookbook Plantasia: A Vegetarian Cookbook Through Asia leverages Asia’s techniques and flavour combinations to expand your repertoire of vegetable dishes deliciously beyond Western-style salads. Pick up your copy here. It is mostly vegan (or easily veganised), with plenty of allium-free options.

Baechu kimchi

Makes 1 wombok’s worth