Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every week, you’ll be receiving historical tidbits, personal stories, and recipes delivered straight to your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. My cookbooks Wet Market to Table and Plantasia are available for purchase here and here respectively. Thank you for being here and enjoy this week’s post. ✨

Whenever the weather warms, I instantly crave acidic things and one of the simplest, most gratifying things to make is dongchimi. Also known as water kimchi (mul kimchi), dongchimi is basically kimchi that is made with a brine, much like traditional Western-style pickles.

Traditionally, it is made in late autumn or winter in Korea, as a way to preserve the harvest of daikon radishes. The radishes are stored in brine in earthernware jars buried underground. As it ferments slowly, the brine turns refreshingly tangy and can be enjoyed with the crisp radish. In the cold, it would partially freeze, creating an icy-cold, slushy broth, which was likely what inspired its use as a cold soup base for dishes such as naengmyeon.

Today, modern dongchimi prioritizes a quicker room-temperature fermentation and is widely embraced as one of the easiest kimchi varieties to make. It involves minimal ingredients and involves no complicated techniques — all you need is to salt radishes, submerge them in brine, and wait.

PRINCIPLES OF MAKING DONGCHIMI

Dongchimi is sometimes mistakenly thought of as a pickle, and understandably so, because the line between pickling and fermentation is often blurry. Both methods use an acidic brine as a means of preservation, but the main difference lies in when the acid is introduced. Pickling begins with an acidic brine, through the addition of vinegar, for example. On the other hand, with fermentation, you are leveraging bacteria or yeasts to break down natural sugars in the food to create acidity. In other words, pickling is a chemical process while fermentation is a biological process, which provides probiotic benefits and depth of flavour to the fermented food.

Unlike vinegar-based pickles, dongchimi lies firmly in the fermented food camp and relies on lactic acid bacteria (LAB) to ferment the sugars in radishes, producing tanginess and live cultures.

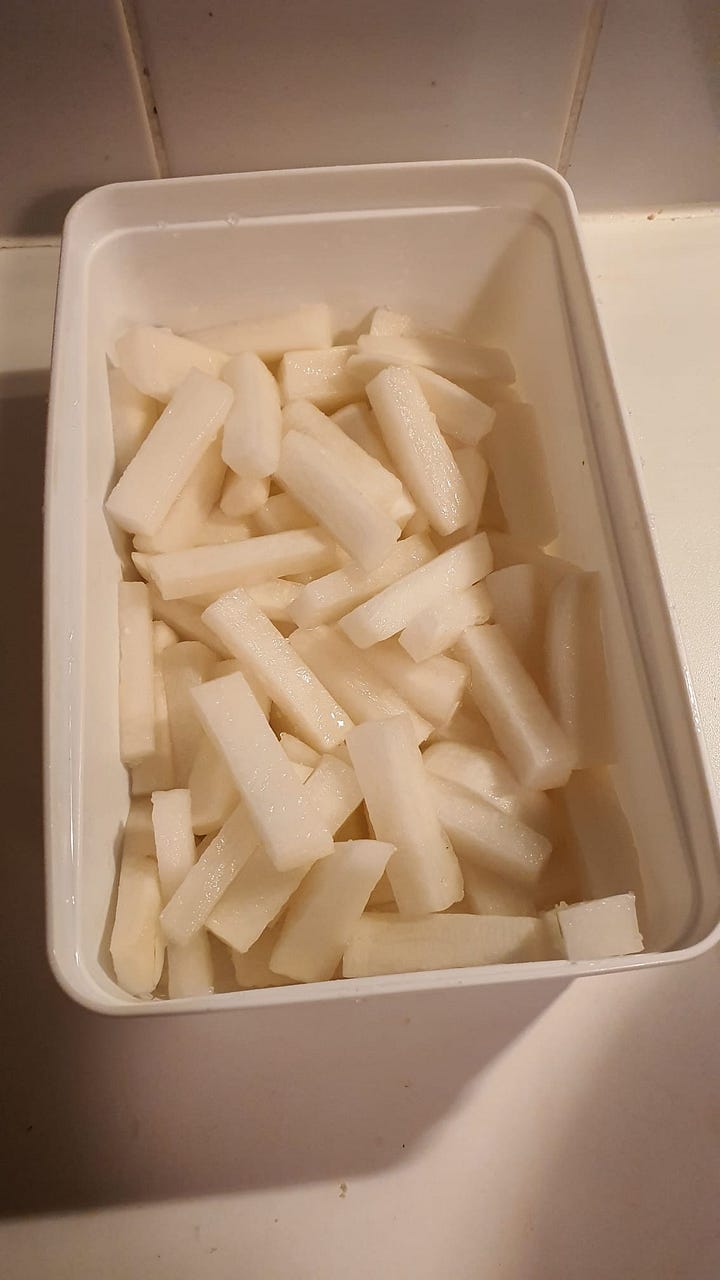

1. Cut radish.

Because dongchimi was originally invented to preserve radishes for a long time, radishes were traditionally deliberately left whole and skin-on, since whole radishes ferment more slowly. This allows bacteria to develop complex flavours over months without the dongchimi brine turning overly sour or the radish turning mushy. However, in modern-day recipes, radishes are often cut to expedite fermentation.

2. Salt the radish.

Salt draws out moisture from the radish, softening the radish’s rigid cell structure and leading to a crisp but tender bite. The salt also seasons the radish internally, so that the brine doesn’t have to be very salty.

The idea here is to be generous with the salt, since the salt also controls fermentation speed and prevents spoilage. Too little salt results in spoilage, but if it ends up turning too salty, you can always dilute the brine or rinse the radish right before you serve it.

In many traditional recipes, the water that leaches out of the radish after salting is retained as it contains lactic acid bacteria, which kickstarts fermentation. However, if your radish is old and bitter, it makes sense to discard this as the radish water will be bitter; dongchimi made without the bitter leached water will taste cleaner and sweeter.

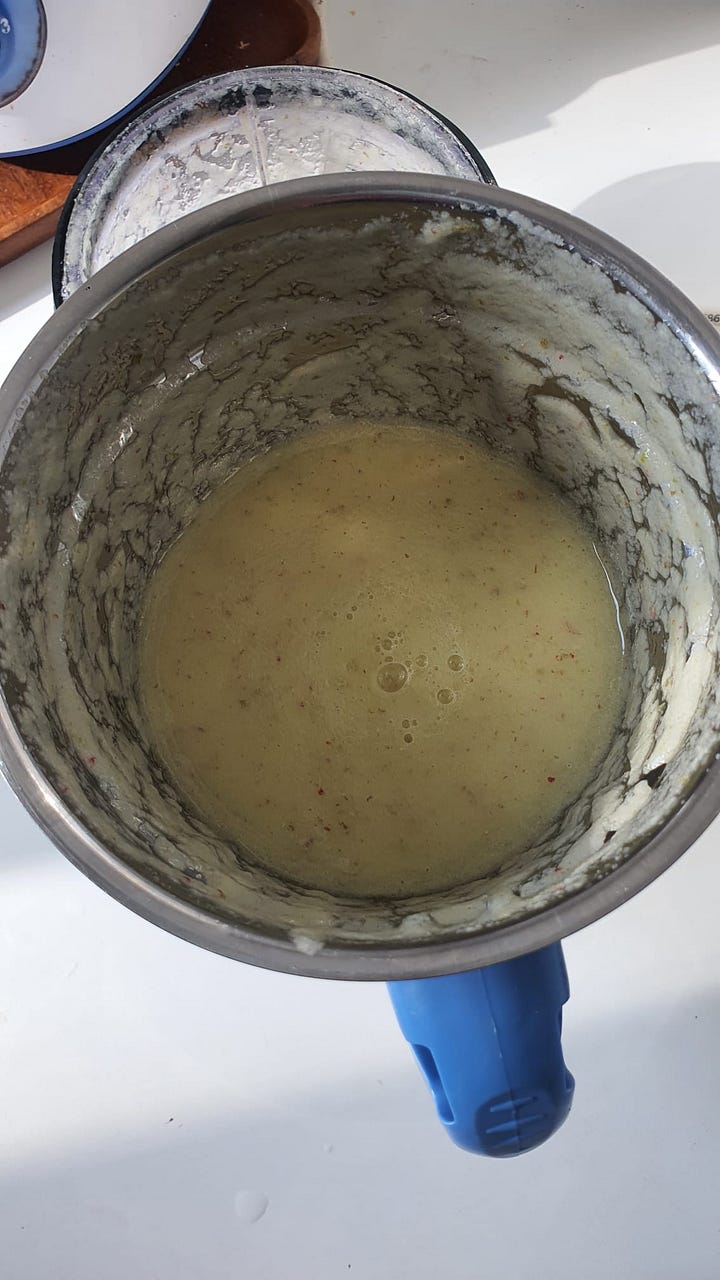

3. Making the brine and add-ons.

Onion, pear, and apple are blended with water and squeezed through cheesecloth to create a brine. The pear, apple, and onion provide the bacteria with extra natural sugars to feed on and deepen the broth’s savoury-sweet profile. In some recipes, potato and rice are blended into the brine for the same reason. For extra umami, some cooks use kombu water in place of regular water.

The garlic, ginger, and chillies are often left unblended so that they can release their flavour slowly during fermentation, while avoiding overpowering sharpness in such a delicate broth.

4. Fermentation

Bubbles are a good sign as these indicate lactic acid bacteria activity. Tasting your dongchimi daily will also help you track its tanginess. The dongchimi is ready when you see bubbles on the surface and there’s a refreshing pop of acidity. The radish should still be crisp. This will take mere days to a week, depending on the ambient temperature. If there’s grey, black, red, pink or orange mold forming, throw out the dongchimi.

If you’ve accidentally over-fermented it and the radish has turned mushy and the broth intensely sour (assuming that your dongchimi is not moldy or foul-smelling), make radish soup! Rinse the sour radish chunks and simmer in anchovy stock with a drizzle of perilla oil and touch of fish sauce. Simmer until the radish turns translucent and tender.

MAKING DONGCHIMI YOUR OWN

Sprite or sparkling water: The use of Sprite in dongchimi is not traditional, but has gained popularity as a way to balance the brine’s saltiness and add a bright, tangy-sweet note. Its carbonation and sweetness mimic the natural effervescence and subtle sweetness achieved through traditional fermentation with fruits like pear or apple. While purists may view Sprite as an unnecessary adulteration, many home cooks embrace it for its accessibility and refreshing taste, especially in summer. An alternative to Sprite is sparkling water.

Fruit juices: In place of Sprite, I like to have fun with different types of fruit juices (with or without sparkling water) to balance the dongchimi. In Plantasia, for example, there’s a recipe for dongchimi balanced with watermelon juice that is immensely summery.

Different vegetables and fruits: Add a sliver of beetroot to the dongchimi as it ferments to turn the brine pink! Try red radish or lettuce leaves instead of daikon radish! Add freshly squeezed tangerine juice to the apple and pear brine — the sky is the limit! Water kimchi is really a springboard for creativity.

HOW TO ENJOY YOUR DONGCHIMI

Cold noodle dishes: The umami-rich dongchimi brine is excellent as a soup base for cold noodle dishes, such as in naengmyeon. For mul naengmyeon (물냉면) that features a clear broth, mix the dongchimi broth with beef or anchovy stock. Adjust the sweetness with fruit juice, if desired. Serve chilled with the daikon pieces, sesame seeds, cucumber, hard-boiled egg, and buckwheat noodles. You can also make bibim naengmyeon (비빔냉면) by tossing the noodles with bibim sauce before adding the broth.

With roasted sweet potatoes, a Korean winter classic. Jihee Shin talks about this traditional pairing in my book Plantasia.

As a side dish with hot, rich, and oily dishes such as kalbi, where the dongchimi serves as a refreshing palate cleanser.

Take a well-chilled shot from the fridge! On really hot days, it’s as refreshing as gazpacho. Add a splash of sparkling water for a savoury equivalent of a fizzy drink. Wex says that this makes a great recovery drink!

Dongchimi

Makes 1 daikon’s worth