Taro croquette or 'wu kok’ 芋角 (pictured below, left) is a pastry that you’d find at traditional dim sum parlours. In one bite, you get three distinct textures: a shatteringly crisp exterior, rich and smooth taro paste, and a cornstarch-thickened meat/seafood filling.

In Singapore, this dim sum staple serves as inspiration for yam ring, a local favourite. Hooi Kok Wai, one of the most influential Cantonese chefs in Singaporean food history, was said to have invented the dish in the ‘60s to woo his wife, an orphan raised by a nun. Drawing inspiration from his classical Cantonese training, he shaped the taro croquette dough into a ring to mimic a Buddhist alms bowl and filled it with an assortment of stir-fried vegetables (middle photo). The nun was pleased by his vegetarian offering, and the dish gained so much popularity in Singapore that virtually every zichar restaurant has it on their menu today. Another variation of the dish in Singapore sees the same dough being wrapped around boiled scallops (photo on the right).

The success of these dishes lies in creating a crust that resembles a bird’s nest or honeycomb. The more lacy and cratered the exterior is, the better. The biggest misconception is that the unique crust is the result of a batter, but the truth is that these dishes owe their crunch to the dough itself. Here are the key steps of preparing this dough:

Wheat starch is mixed with boiling water to form a dough.

Steamed taro is mashed and mixed into the wheat starch dough.

Finally, some form of fat is mixed into the dough. Traditionally, lard is used, but vegetable shortening or butter could also be used with success.

The main question that I had was: What exactly is causing the honeycomb structure? Is it something about the composition or structure of taro that causes this reaction when the dough hits hot oil?

Honeycomb structure

Looking at the craters on the crust, my first thought was ammonium bicarbonate 臭粉, a leavening agent in traditional recipes for fritters and steamed treats. According to Periuk, this was used in European recipes for cookies and biscuits as well before the advent of baking powder. The problem with ammonium bicarbonate is that it releases both ammonia and carbon dioxide when decomposed; this is why some chefs shun the ingredient in favour of baking powder instead. Still, there are some recipes that do away with leavening agents altogether. Could it be the taro then?

I found a version of this pastry made with boiled egg yolks in Andrew Wong’s cookbook, which ruled out the idea that it was the taro that produced the honeycomb effect. It was intriguing, substituting egg yolks for steamed taro, but it made sense - after all, the two share the same fluffy, powdery texture when cooked.

The lightbulb moment came when I came across this video below, in which the chef describes the dough as ‘su’ 酥, or laminated pastry. Because the fat is incorporated fully into the dough, rather than being layered like Teochew mooncake pastry or folded like puff pastry or croissant dough, it had not crossed my mind that the dough is essentially a laminated pastry.

According to the chef, the history of this pastry spans centuries. A noodle seller was working with some dough (one could only guess that it was a starch-based dough). When it stuck to his hands, he added some oil to prevent it from sticking, and the oil got incorporated into the pastry. When he accidentally dropped it into a vat of hot oil, he was surprised by the honeycomb structure that formed; the discovery created a new genre of Chinese pastry.

Starch gelatinisation

Multiple dim sum chefs on Youtube stress that the proper gelatinisation of wheat starch with boiling water is key to the success of the dish. I did a quick experiment with two doughs, made solely with boiling water, wheat starch and lard:

A (left): Boiling water was added to wheat starch to form a barely moistened, dry dough. Lard was rubbed in.

B (right): Boiling water was added to wheat starch to form a dough that feels as soft and supple as a earlobe. Lard was rubbed in.

The textures of the final dough were remarkably different. A had an almost flaky texture when the fat was added, like solidified candle wax (left). But when the wheat starch dough was supple, the fat incorporated easily (dough on the right):

The effect of temperature

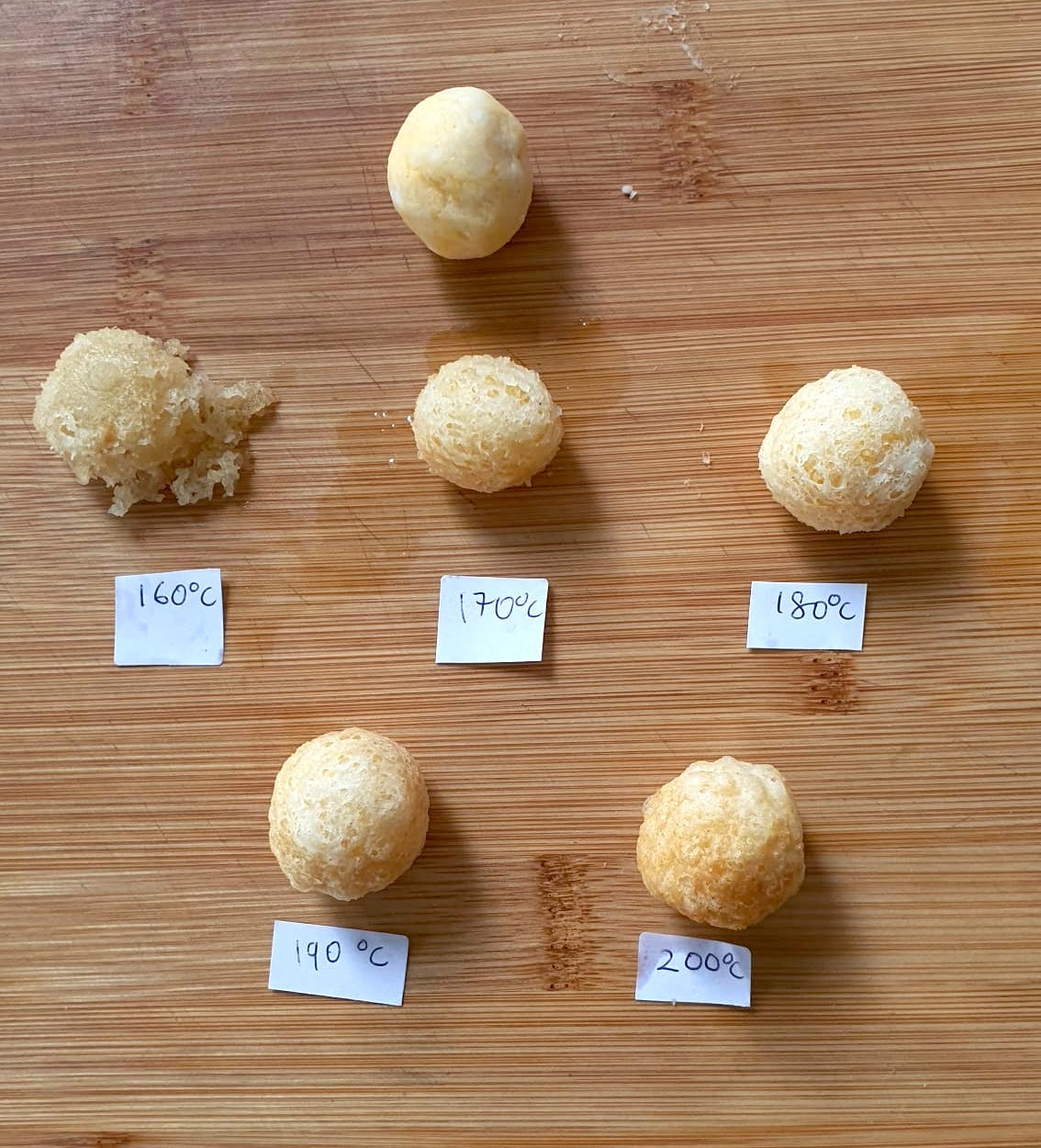

Another factor that was key to the success of the pastry, according to the chefs, was frying temperature. I took B, the properly gelatinised lump of dough, and fried it at temperatures ranging from 160°C-200°C. What I noticed was that at lower temperatures, the honeycomb effect was more pronounced, but the dough also demonstrated a greater tendency to disintegrate. At high temperatures, the honeycomb effect was less pronounced. In the dim sum world, this is because the dough is “fried to death” 炸死 - a crust had formed on the dough before the honeycomb strands had time to develop.

I also fried a small lump of dough A, which had improperly gelatinised wheat starch and poorly incorporated lard. Rather than a honeycomb, what resulted was an ugly, porcupine-like appearance. When bitten into, it had the poorest textural properties, with the dough falling apart into a mess of sandy crumbs at the slightest pressure.

This small series of experiments taught me a few things:

It confirmed that taro is not crucial for the formation of a honeycomb structure; a dough of wheat starch, boiling water and fat is sufficient. The honeycomb structure could be explained by the fat being incorporated (laminated) into the wheat starch dough and seeping out of the dough as it is fried, forming craters.

Proper gelatinisation of wheat starch is important for both visual appeal and texture of the fritter.

The ideal temperature for achieving the most dramatic honeycomb is one where the exterior separates enough from the dough for the honeycomb structure to be exaggerated, but not so much that the fritter literally disintegrates in the oil.

Vegetables for flavour and colour

At this point, the croquettes had little going for it other than a subtle egg yolk flavour and the fragrance of lard. They were also barely browning. This made me realise why chefs add taro to the dough:

Taro contains sugars that contribute to browning when fried.

Taro adds a sweet, earthy flavour to the fritter.

Mashed taro adds creaminess to the interior of the fritter.

I was curious to see if other vegetables could be used in place of the taro in this fritter, especially since I now live in Europe and taro isn’t the easiest to find. Taro is one of the starchiest vegetables in the world, with starch making up 70-80% of the whole dry matter. Potatoes are pretty close, with 60-80% starch, but lack flavour. I decided to go for sweet potatoes in the end (45% starch content) when I found some gorgeous purple sweet potatoes at my local Asian grocer, and filled them with a prawn and pork mixture.

I fried them at 170°C and was thrilled with the results. The honeycomb was apparent, and the colour and texture were beautiful. Sure, sweet potatoes are sweeter and have a different flavour from taro but they were a terrific substitute.

This dish is a great one to prepare ahead of time, for a party or gathering. Once the dough is made, it stores extremely well in the refrigerator. Because the dough and the filling are fully cooked, all you have to do when your guests arrive is to focus on getting the crust right. And once you learn how to prepare this type of dough, the possibilities are endless:

Wrap the dough around boiled seafood like scallops or prawn (see Jumbo’s version here)

Wrap the dough around boiled eggs, so it resembles a scotch egg (see Andrew Wong’s version here)

Press the dough onto braised, boneless duck (see this video here). This is rather popular in Taiwan.

Make savoury croquettes, filling them with meat, seafood or vegetables. The dough can be made with lard, butter or vegetable shortening with success - so you could easily turn this into a vegetarian dish. The filling should be fully cooked, and preferably cornstarch-thickened and saucy to balance the dense, creamy root vegetable paste. For a fancy touch, you can make edible swan heads and attach them to the croquettes like this.

The flavour of taro and sweet potato works well in sweet applications too. I have seen sweet croquettes, with a truffle centre that melts as the croquettes fry.

If you can’t be bothered to make individual croquettes, shape the dough into a yam ring. Fill the deep-fried ring with anything from stir-fried vegetables to gong bao chicken. Like the savoury croquettes, a cornstarch-thickened, saucy accompaniment works best.

The recipe for the croquettes and detailed steps will be in a separate email for paid subscribers. Thanks for following along! 🤓

My goodness! You are doing great experiments for this laminated pastry. Thanks so much for your information!!!