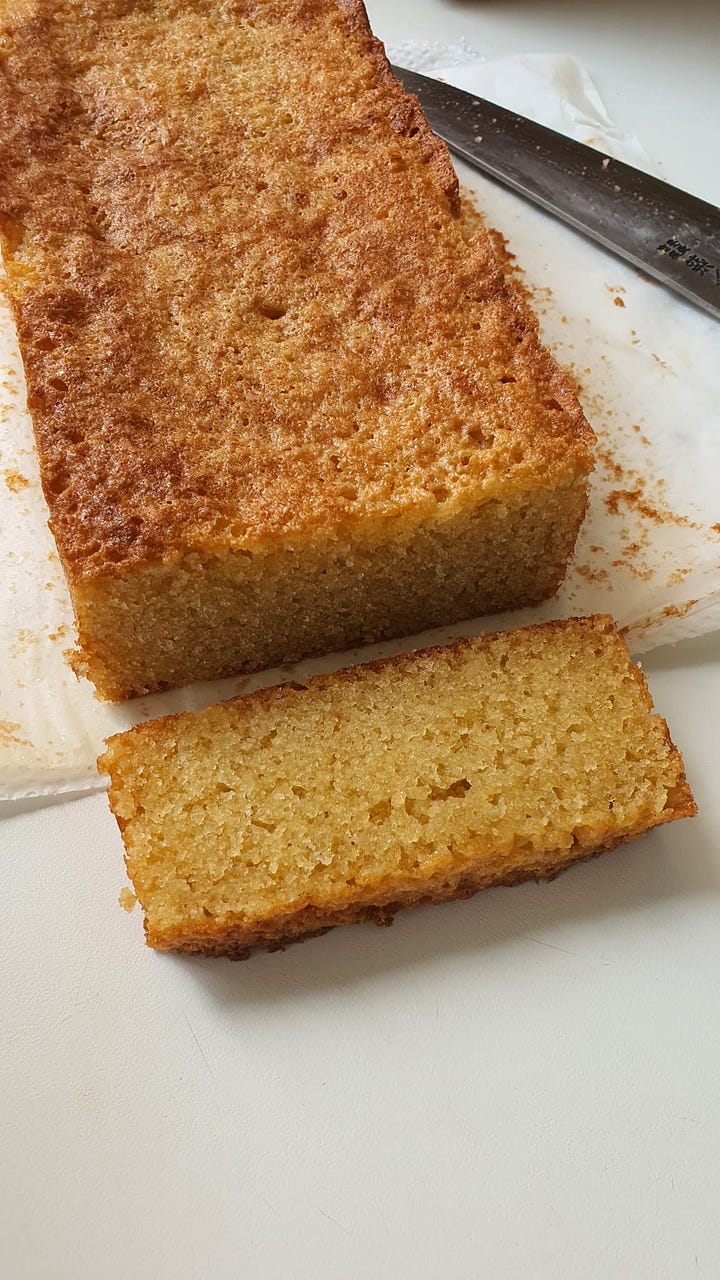

Readers of this newsletter would know that I’ve written about sugee cake on multiple occasions, but so far, while I’ve described my past iterations as rich, sinful, and dense, there’s been one trait that has been eluding my cakes: syrup cake-level moistness. Because sugee cake is heartstoppingly rich, I’ve been spacing out my trials over the past couple of months and finally conceded success when my husband, who’s typically nonchalant about dessert, voluntarily cut himself a slice, and then another.

Before we jump straight into the deep-dive, I thought I’d show you a quick comparison of a not-so-great sugee cake that I made over Christmas (left) and my new winner (right):

History of sugee cake

The first time I heard of the cake was in 2020, when cookbook author Sasha Gill described it to me as the most representative dish to the Eurasian community in Singapore. “Whenever someone asks me about Eurasian cuisine, I think not of curry devil or pang susi - undeniably two of the most Eurasian dishes - but of sugee cake. It is a cake made out of semolina, butter, and an ungodly amount of egg yolks (it’s in the double digits)… It is brought out whenever there is anything to be celebrated - for such an indulgent cake requires a bit of festivity. It was what I had every birthday, Christmas, Easter, and every event in between.”

Sugee cake is a rich and buttery cake made with semolina (“sooji” in Hindi), a coarse flour made from durum wheat. While there is a litany of semolina dishes made largely on stovetops in Asia, semolina was only incorporated into baked sweets in the region under Portuguese rule in the 15th century. As the nuns of Portugal used to clarify their wine and starch their habits with egg whites, leftover yolks were turned into all manner of cakes, custards, and pastries. Like these Portuguese treats, sugee cake has a sunny yellow crumb which coats fingers and lips in an oily sheen, a tell-tale sign of its decadence. Another defining trait of sugee cake is its grainy crumb, owing to the use of semolina. “Like rice,” I was once told.

Semolina

Sugee cake (or sooji cake) is a derivative of pound cake, the latter so named because it was classically made with a pound each of butter, sugar, flour, and eggs. Indeed, recipes from Eurasian cooks from Malaysia and Singapore reflect that, while maintaining pound cake proportions, sugee cake replaces part of the flour with semolina. In some recipes, the semolina even completely replaces flour:

Compared to the types of wheat (hard red, hard white, soft red, and soft white) that are used for your standard supermarket flours, durum wheat, from which semolina is derived, is the “hardest” of them all. What this means is that semolina has a high protein content (13%) that makes it excellent for food items requiring gluten formation, such as bread and pasta. When used in cake batter, semolina lends a unique chewy, dense texture to the final product. While some bakers utilise semolina exclusively for texture, others swear by toasting the semolina as it deepens the flavour to one that is nutty and popcorn-like.

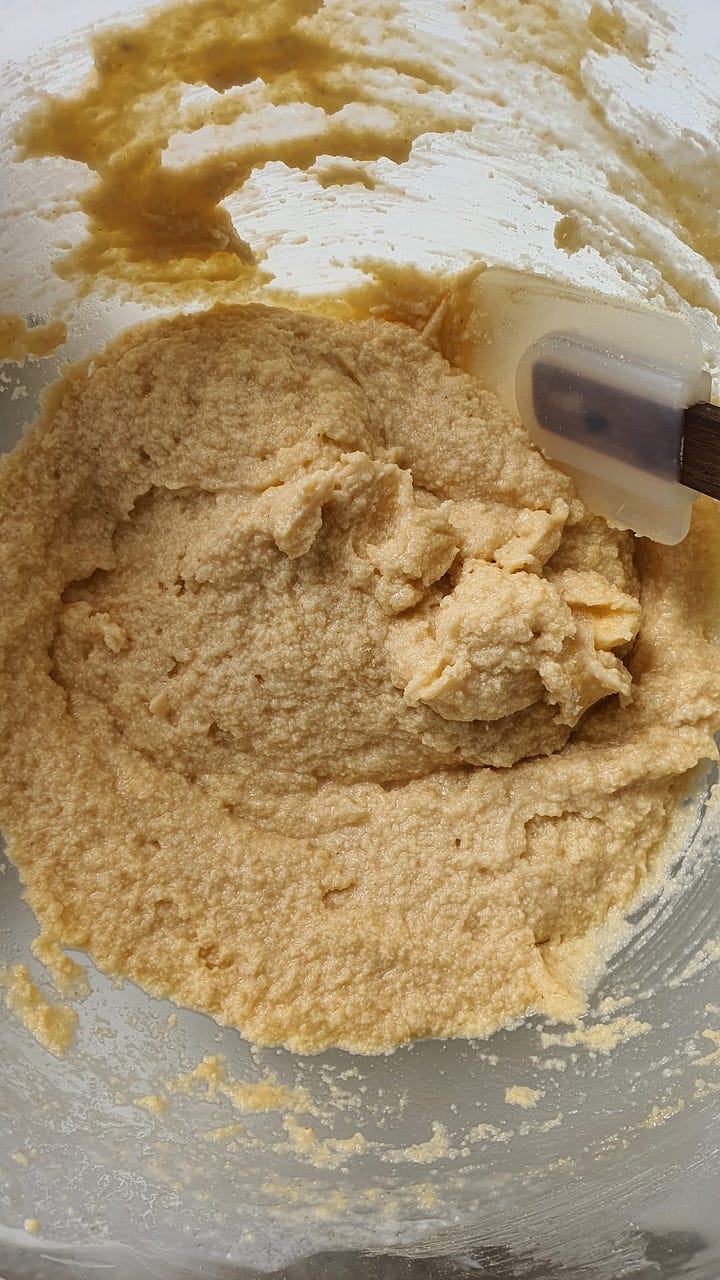

Because of semolina’s high gluten content, it is combined with the creamed butter after it is toasted - the fat coats the proteins in the semolina, thus inhibiting gluten formation and allowing for a more tender cake. While some recipes instruct the cook to “soak” the semolina in butter for at least several hours so that it loses its grittiness, I’ve made sugee cakes with and without an overnight soak and have observed that it makes little difference as long as the semolina is finely milled (it should be fine as sand).

Almonds

Apart from semolina, sugee cake is also known to contain a measure of nuts. While bakers in Sri Lanka use cashews in their love cake, almonds tend to be the nut of choice in a sugee cake. In the days before store-bought ground almonds were widely available, bakers would blanch almonds and peel off the skins before finely chopping or grinding them by hand. Though ground almonds is ubiquitous these days, some recipes like Melba Nunis’ omit them, in favour of chopped almonds, which provide crunch in every bite. Ground almonds, however, is able to form part of the structure of the cake while being gluten-free, enhancing its fat content and thereby improving its tenderness. Some cooks also tell me that the nuts allow the cake to improve with age, as they release their own incredible richness to the crumb over time (an observation that I can attest to). Because I don’t want chopped almonds to detract from the soft, rubble-like texture that the ground almonds provide, in tandem with the semolina, I used only ground almonds in my cake this time.

Brandy and other flavourings

While semolina cakes made by Indian and Sri Lankan cooks tend to be flavoured with rosewater, Eurasian sugee cakes are heavy on brandy. In her blog, Melissa de Silva writes that sugee cake should be “impregnated” with brandy so that it leaves a “perfume of sweet, curranty mellowness.” I had been rather shy on the booze with my past attempts of sugee cake, so this time I added a liberal pour of ginjinha (brandy infused with sour cherries from Portugal) that I had on hand and it immediately became the core flavour of the cake. The added benefit was that the resulting cake was super moist from the added liquid.

Eggs and baking powder

Almost everyone who talks about sugee cake points towards how rich it is. It not only features lots of butter, but also often has a higher yolk to white ratio. As whites are 90% water and 10% protein and yolks are 50% water with 50% being fat and protein, the ratio of white to yolk determines the end texture of the cake. A yolk-heavy cake will be rich, dense, and substantial, while having a flavourful and golden crumb. In almost all the recipes that I looked at, the egg yolks outnumber the whites, the only exception being Wendy Hutton’s recipe, which uses an equal number of both:

Besides affecting the flavour and richness of the cake, eggs serve as leavening. In a traditional pound cake, there is no chemical leavening such as baking powder, so it depends entirely on the air incorporated into the batter by way of the beaten eggs. Most, if not all, sugee cake recipes call for the egg yolks to be added to the butter and semolina mixture, and for the whites to be beaten. This allows for a dense and rich, yet paradoxically light texture. Comparing these cakes to my recent trial which leavens the cake only by baking powder, the former has a fluffier texture (think Asian-style banana cake), with a heavily caramelised, soft crust that can be peeled off the cake. On the other hand, my recent sugee cake, made without beating the whites, has a tender yet pleasantly dense texture. Both are good, but what this experiment showed me was that you don’t have to beat whites to obtain a delicious sugee cake.

Aging the cake

Owing to the nuts in the cake, the texture of sugee cake changes rather dramatically after it is baked. Fresh out of the oven, it is moist and heartbreakingly tender. A day or two later, the cake becomes even denser and richer than before. Because I didn’t take a photo of the cake after the first day, the photo on the right is from my friend L whom I gifted some of the cake to. She described the crumb as being “plush” and “buttery but not cloying”, reminiscent of “ricotta cake”. Even though not beating the eggs for this cake is highly untraditional, this version comes closest to my own sugee cake ideal! I encourage you to suspend you skepticism and try it because the proof is in the eating.

Sugee Cake

MAKES A 9-BY-4-INCH (23-BY-10-CM) CAKE