Rice-cooker coconut rice

With cooking, the simplest things are often the hardest to perfect. Like an omelette. Or coconut rice. Coconut rice is the central component of nasi lemak (‘fatty rice’), one of the most popular hawker dishes in Singapore. This is traditionally a humble Malay dish, a way to tap on the resources on our island. Terry Wong of the blog The Food Canon suggests picturing a “seaside Malay village”, where “the typical family with simple means will eat off the sea and land”. Coconuts from the many trees that line the shores would be harvested and used to cook the rice, which is often served with dried anchovies, sambal, cucumber and fried fish. The classic choice for the latter, according to Khir Johari, author of The Food of Singapore Malays, is the yellowtail scad (selah kuning) as it is economical.

With affluence, nasi lemak has evolved into something luxurious and you can find all sorts of accompaniments to the rice at hawker stalls, from beef rendang to curry chicken. Despite this, Khir Johari says, “The main actor is the rice itself. A good nasi lemak stands on its own. If you need all the side dishes to make nasi lemak delicious, then your nasi lemak is not quite there yet.”

Nasi lemak kukus

Recipes for coconut rice seem simple on paper, involving essentially the same three ingredients - coconut milk or cream, water and rice. Unlike regular steamed rice, coconut rice is always salted to enhance the fragrance of the coconut and to cut its richness. Other additions are up to the cook - some hawkers use pandan exclusively, while others add a slice of ginger or galangal, or a bruised stalk of lemongrass.

Nasi lemak tends to be cooked at hawker stalls in large rice-cookers via the absorption method (i.e. the rice simmers in liquid until all the liquid is absorbed). However, there’s a method that is deemed superior by some - the ‘kukus’ method, or the steaming method. Rice is soaked overnight and steamed until it is partially cooked. Then, it is combined with coconut milk and allowed to rest and absorb all of the goodness, similar to the way an airy sponge soaks up milk in tres leches cake. The rice is then steamed a second time until it is fully cooked. Chef Damian D Silva demonstrates the kukus method in this video.

According to Gerald Chai in “Mum’s Favourite Recipes Presented Through a Journey in Time”, the kukus method produces rice with “a world of difference to the nasi lemak as compared with the customary boiling method“. Leslie Tay of ieatishootipost who has reviewed several hawker stalls serving nasi lemak kukus claims that this method “results in a rice which has a bit of a grainy bite, much like pasta that has been cooked al dente”. Because the coconut milk is not cooked with the rice from the start, the rice has a “bright and fresh coconut aroma as the coconut milk is not overcooked”.

Comparing coconut rice recipes

For the purposes of home-cooking, I wanted to develop a good recipe for preparing coconut rice with a rice-cooker. It is far more practical, plus how many of us would have the foresight to soak rice the night before for today’s dinner?

I gathered recipes from a couple of heritage cookbooks written by legends and authorities in their own right - Melba Nunis, a champion of Kristang cuisine based in Malaysia; Mandy Yin, cookbook author and restauranteur of Sambal Shiok in the UK; Shamsydar Ani, a Masterchef Singapore finalist and someone who is passionate about making Malay cooking accessible to the younger generation; Terry Tan and Christopher Tan, two very established names in the local cookbook scene; and Debbie Teoh, a Nonya cookbook author and chef who is known for her kueh.

Like baker’s percentages that express ingredients as percentages of the weight of flour, I found it easier to compare the recipes by expressing the coconut milk and water as percentages of the weight of rice:

It was surprising to note that the quantities of water and coconut milk varied widely across the board - from 63% to 200% for water and 50% to 94% for coconut milk! I figured that a good starting point would be Terry Tan and Christopher Tan’s recipe, given that the quantities fall somewhere in the midpoint of the ranges and were pretty similar to Mandy Yin’s recipe in Sambal Shiok.

100% rice, 83% coconut milk, 83% water - all cooked together

The rice is first rinsed until the water runs clear. This is a step that is emphasised in multiple nasi lemak recipes as this washes off the starch and prevents the rice from being gummy. The washed rice, coconut milk, water and salt are then combined and cooked together in a rice-cooker.

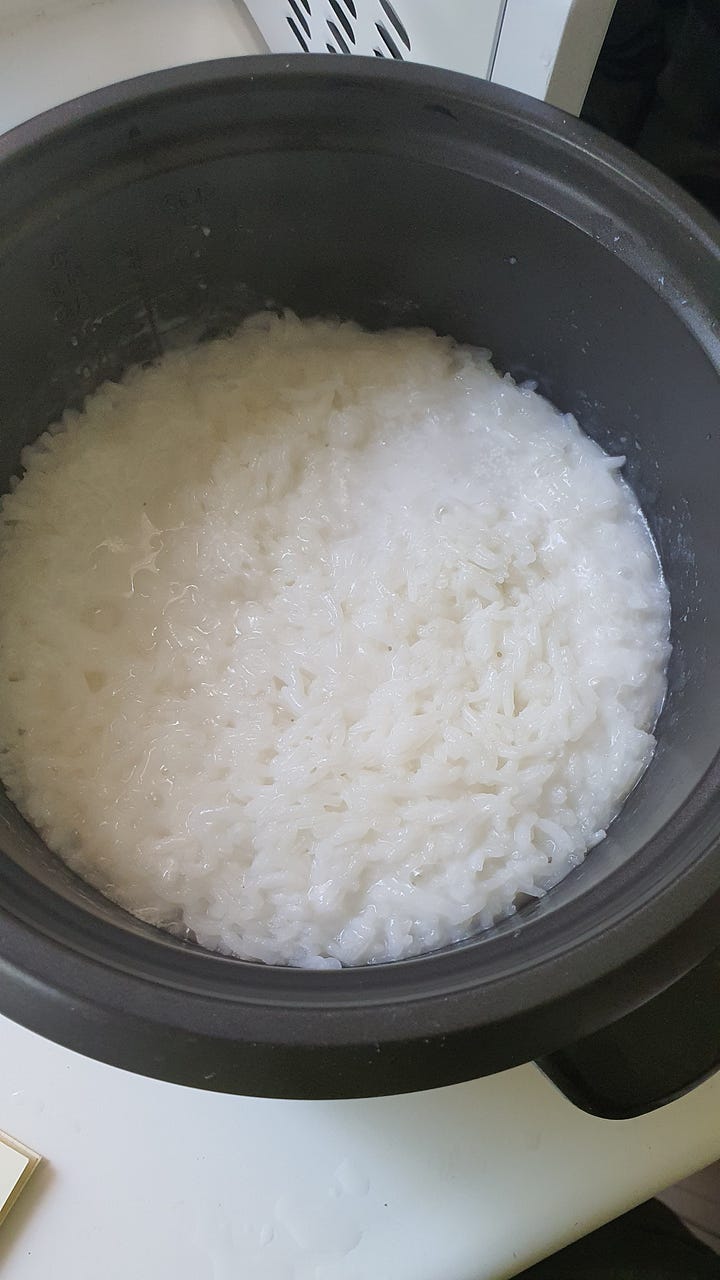

At the end of the cooking, the rice had a moat of coconut fat on the top - not the most appetising thing to look at. This phenomenon is easily explained: when coconut milk is cooked with rice, its water content evaporates along with the water in the pot, causing the fat to separate from the solids. This is known as “cracking”, an intentional first step in Thai curries, where the coconut milk is cooked until it separates into coconut curds and fat. This allows you to fry your curry paste in coconut fat. However, in coconut rice, this is definitely not desirable.

This said, I’ve seen many recipes and video tutorials online that involve cooking the rice with coconut milk from the start and the “cracking” does not occur. It might boil down to the percentage or type of coconut milk used.

I proceeded to fluff the rice, the coconut fat clinging onto the grains of rice like whipped cream as I did so (see the photo below).

Flavour: Overly rich, almost as though I was eating mango sticky rice.

Texture: The rice didn’t taste like it was fully cooked through. It was very grainy and al dente, and when fully cooled, felt dry and oily in the mouth. A quick internet search shed light on this - what likely happened is that the oils from the coconut milk coated the rice and impeded the grains’ absorption of water.

100% rice, 50% coconut milk, 200% water - coconut milk added towards the end of cooking

Shamsydar’s recipe seemed like the next logical step - her recipe uses the lowest quantity of coconut milk and highest quantity of water. I figured that the lower amount of coconut milk would reduce the overly rich mouthfeel, while more water would help the rice cook through.

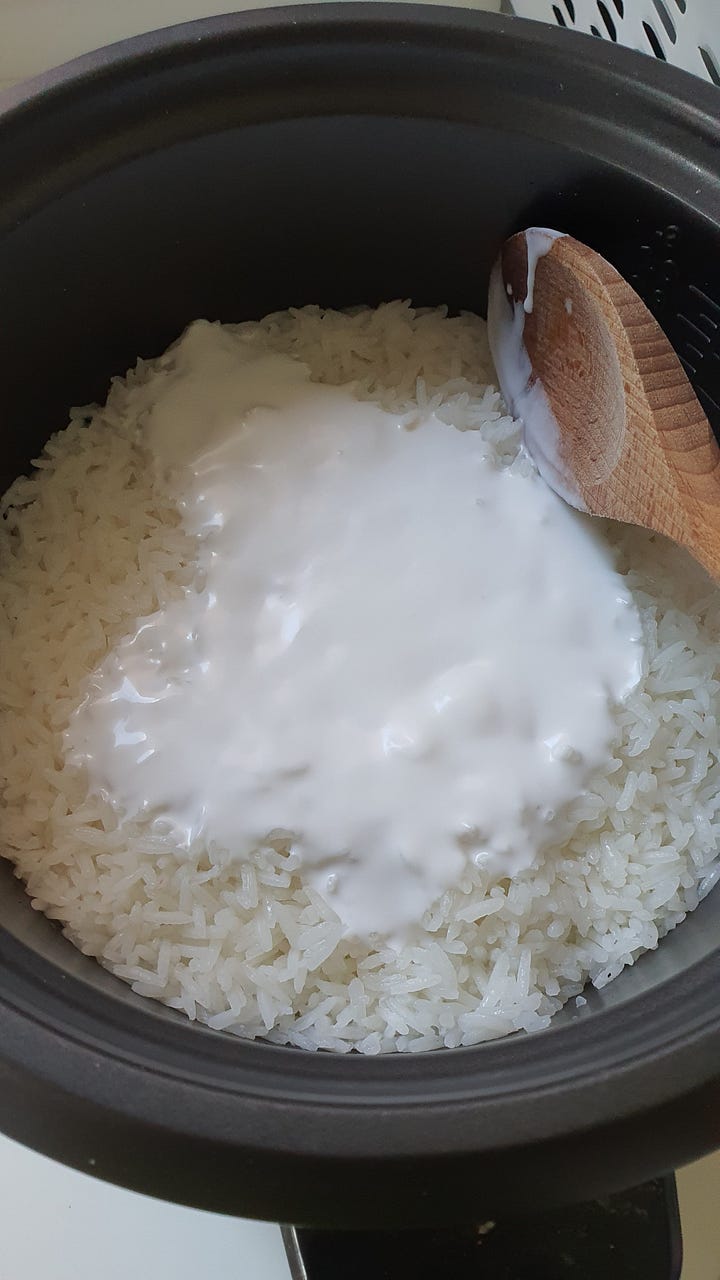

Her recipe is also interesting because it calls for the coconut milk to be added when the water is almost fully absorbed by the rice. I waited for craters to form in the rice before adding the coconut milk, and stirred it through with my spatula gently. It was as beautifully creamy as rice pudding. The rice continued cooking until my rice-cooker flicked to “Warm”.

Flavour: Even though the quantity of coconut milk was low, the rice tasted rich and not at all lacking in coconut fragrance.

Texture: It looked porridge-like initially, but the rice continued to absorb more liquid after resting covered for 10 minutes. Still, the final result was too wet and sticky for my liking, almost verging on mushy. (I have to say that the original recipe calls for basmati rice which might absorb water differently from regular jasmine rice.)

100% rice, 63% coconut milk, 100% water - coconut cream added at the end

Debbie’s recipe was a good average of the first two recipes I tried. This time, I cooked the rice entirely in the water until the rice-cooker switched to “Warm”. The rice tasted al dente when I added the coconut cream, but after sitting for 10 minutes, covered, it was moist and rich. There was no split coconut fat on the top.

It was coconut rice that I was happy with, but it got me thinking: I’ve sometimes heard that the holy grail of nasi lemak rice should be fluffy with separate grains. Yet, I wouldn’t describe this rice to be fluffy. Is fluffy, light, separate-grained nasi lemak even a thing? I’ve never had nasi lemak like that but it was worth an investigation.

Basmati vs jasmine rice

Enter basmati. Basmati nasi lemak is new to me but there are many recipes for basmati coconut rice online. There are hawkers who make nasi lemak with basmati rice, but they are few and far between. This is probably because basmati rice is more expensive, so hawkers with low price ceilings to work within would hardly think to use it. On the difference between nasi lemak made with basmati and jasmine rice, Leslie Tay writes about basmati coconut rice, “It isn’t as moist as jasmine rice when cooked, so it doesn’t feel as rich on the palate. But the advantage of basmati rice is its light and fluffy texture… you can finish a whole bowl of rice without feeling too jelak (stuffed).”

There are of course detractors who argue that basmati nasi lemak is not real nasi lemak because it has a different mouthfeel from that made from jasmine rice.

Now that I was getting close to something that I was happy with, I flavoured the rice this time around with a bruised lemongrass, a slice of ginger, and knotted pandan leaves. Like my last trial, I added coconut cream right at the end of the cooking.

The difference in texture was immediately discernible. Like jasmine rice, the basmati coconut rice was tender and moist, but it had a slight graininess to it which is not at all unpleasant. After tasting both side by side, my preference is for the basmati coconut rice - the grains were fluffy and light, while still being rich. A very satisfactory result with minimal effort. I’ll leave quantities of ingredients for jasmine rice and basmati rice down below so you can cook both and decide for yourself!

There are many dishes you could pair the coconut rice with, but the general consensus is that, because coconut rice is rich, you want to eat it with dishes that are lighter. Pailin from Hot Thai Kitchen recommends something like tom yum or som tum (green papaya salad), for example. That said, there are hawkers who serve beef rendang with their nasi lemak, so who’s to say you can’t?

Coconut rice

Serves 2-3