Muah chee 麻糍

As I mentioned in a newsletter two weeks ago, I’ve recently begun teaching cooking classes in the Netherlands. There are many benefits to this: one, it helps pay the bills while working on my next cookbook (yes, already! but more on this another time.) Two, it gets me out of the house and meeting new people. And three, I’m able to bring recipes that I’ve developed in my home kitchen out into the world and see how they fare with actual cooks and eaters.

What I’ve noticed is that it isn’t difficult at all for Dutchies to love our savoury food, but many Asian sweets are often way outside of their comfort zones. Unlike Western desserts that are made with copious amounts of eggs and dairy, many Asian desserts, as I explore in my cookbook Plantasia, are centered around root vegetables, fragrant herbs and grasses, coconut, beans, and lentils. With starch as the structural basis, the textures championed in these treats are glutinous, chewy, and QQ (springy) rather than being conventionally fluffy, tender, or creamy.

My strategy has been to ease them into it by pairing the unfamiliar with the familiar, and the most well-received dessert so far has been glutinous rice balls with peanut butter (the Dutch love their pindakaas). Each dumpling encloses a chilled ball of peanut butter creamed with sugar and butter, before it is lowered into simmering water. As the dumpling cooks, the filling melts into lava, contained by the surrounding chewy dough - the result is a molten, explosive bite of peanut butter, like a culinary magic trick. (The recipe for these dumplings with black sesame / peanut butter can be found here.)

When I taught this dessert last Friday, I was pleasantly surprised when a participant told me that he had always wanted to make mochi ever since he watched a Youtube video of Japanese mochi being pounded and then coated in kinako (soybean powder). My thoughts immediately drifted to muah chee, or Chinese mochi. Muah chee is made from glutinous rice flour, water, and oil, and the resulting dough is cut into bite-size pieces on a tray filled with ground peanuts and sugar. Eaters are provided with toothpicks to pierce each soft drop. The mochi itself has very little flavour - its pleasures being textural - so it relies on the peanut rubble to provide nuttiness, crunch, and sweetness with the barest whisper of salt.

It is the kind of snack that many Singaporeans grew up eating at the night markets (pasar malam) or purchasing from the itinerant hawkers who set up shop in the middle of the heartland towns. Simple nostalgic snacks such as these tend to be the first to become endangered in the local repertoire of dishes, mainly because their plain simplicity is often overshadowed by more glamorous or novel treats. Made with humble ingredients, there is also an expectation for them to be dirt-cheap - S$3.50 for 15 pieces of muah chee is considered exorbitant, while Japanese mochi, made with similar ingredients and methods, when presented as wagashi and served in conservative portions, is perceived as poetic and a high form of culinary artistry.

An institution for muah chee in Singapore is Hougang 6 Miles Famous Muah Chee located at Toa Payoh HDB Hub, which food Youtuber and former journalist Gregory Leow covered in the video below. My home was close to the Toa Payoh area when I was living in Singapore so I’ve eaten muah chee from this stall on several occasions, but the conversation I had with the class participant prompted me to consider what separates great muah chee from simply being good for the first time.

The dough

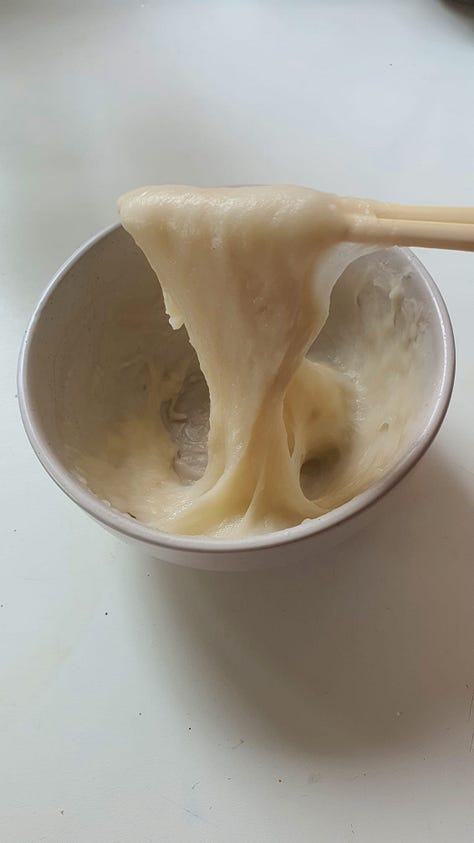

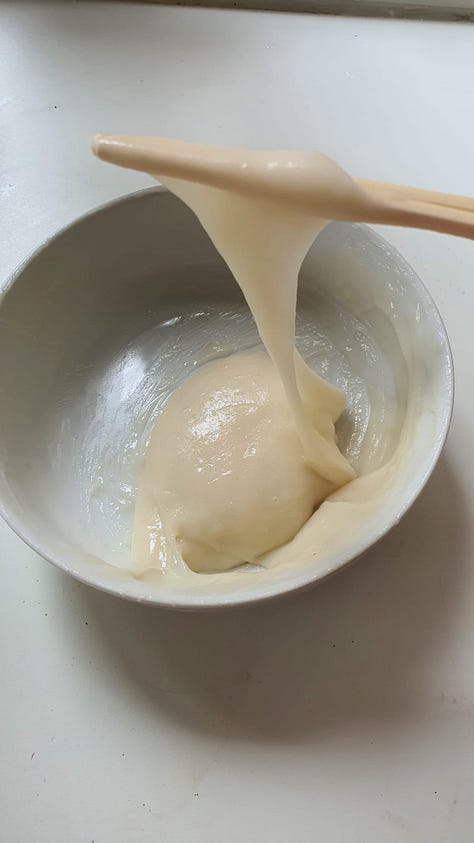

Much of muah chee’s appeal lies in its texture, being soft as a cat’s paw-pad yet simultaneously being stretchy and lightly chewy. The three ingredients - glutinous rice flour, water, and oil - are first combined and cooked until they form a cohesive lump. There are several ways to do this: in a steamer; blasted in a microwave; or stirred and folded into itself repeatedly on the stove. I chose to steam my muah chee because I didn’t want to worry about it being unevenly cooked or burnt, and this method offers greater flexibility for scaling up or down.

While most tend to use vegetable oil these days, Teochew muah chee hawkers opt for shallot oil, made by deep-frying thinly sliced shallots in oil. While this is used widely in many home-cooked or hawker dishes (a dash elevates even the simplest bowl of macaroni soup, for instance), the marriage of shallot oil and sugar is a quintessentially Teochew combination that features in desserts such as orh nee (a voluptuous paste of mashed taro), and ang ku kueh (glutinous rice cake enclosing mung bean paste). Hougang 6 Miles Famous Muah Chee apparently goes a step further and fries their shallots in lard. To those who are unaccustomed to shallot oil in desserts, it might seem like another one of those bizarre savoury-sweet combinations from Asia, like the Taiwanese rolled crepe of crushed peanuts, coriander leaves, and ice cream, but the sweet-savoury fragrance of the shallot oil in muah chee works to intensify the roasted flavour of the peanuts.

Once the dough is cooked, those who are not fussy about the texture of their muah chee can proceed to coat it immediately in peanut, but taking the time to work the dough enhances its chewy qualities. Street vendors in Japan theatrically pound the mochi with long wooden mallets, but hand-stirring, kneading, or pounding the dough with a mortar and pestle works for smaller quantities at home. As a rule of thumb, the more water present in the dough, the stickier and softer it is. While many recipes recommend a 1:1 volume ratio of glutinous rice flour to water, I’ve found success with a slightly greater proportion of flour.

Peanut rubble

The peanut rubble, being just peanut and sugar, seems straightforward, but it is precisely that the ingredient list for muah chee is so short that excellence comes down to the minute details. The most respected hawkers dry-roast their peanuts and grind them themselves instead of purchasing a store-bought mix. But honestly, I didn’t want to go through all that trouble for a small portion of muah chee, so I purchased a bag of roasted peanuts. The first thing I noticed was how pale and anemic they looked, so I fried them in some shallot oil and it made all the difference in flavour and appearance (see the colour difference below). It was like holding up a loudspeaker to the peanuts, in terms of flavour.

Inspired by Hougang 6 Miles Famous Muah Chee, where each bite-size piece is first dipped in fried shallot oil and bits of fried shallot (see the video above), I flattened the dough out in a few tablespoons of fried shallot oil before coating it in the peanut mixture.

The finished muah chee are addictive little morsels (their size having a large part to do with this), with the profoundly reassuring fragrance of warm roasted peanuts. They taste of nostalgia, or 古早味 gǔ zǎo wèi (a taste of former, simpler times), in tangible form. If you are not told that it’s in there, you wouldn’t detect the shallot oil because it is so well-melded with the aroma of the peanuts. If muah chee wore clothes, I’m pretty sure they would wear matching, roomy sets of blouses and trousers in a pastel floral motif. Now that I’ve typed that, I realise that I have just, in essence, described my maternal grandmother. But it fits, because that’s how I feel about muah chee. Not flashy, calling any attention to themselves, or concerned with today’s Instagram-fuelled trends, but I love them anyway, and perhaps even for that very reason.

Muah Chee

MAKES 2 TO 3 SERVINGS