People don’t expect this, but I always get a little nervous when I have guests over. It’s a good sign - the nerves show that you care - but sometimes I do feel intimidated when cooking for seasoned cooks. These are usually those of a different generation who have been cooking for many more years than I have, or those who do it for a living. But then I remind myself that what cooking, particularly home-cooking, is fundamentally about pleasing another.

The more accomplished a cook my guest is, the greater my penchant for keeping things simple. By this, I don’t mean slapdash or plain, but the sort of food that is the gastronomic equivalent of collapsing into bed at the end of a long day. Speaking from experience, when someone who’s always cooking for others shows up at your doorstep, ultimately they just want to be nourished, fed, and nurtured. And if you’re able to express such care through your food, that’s good enough.

Over the weekend, we had our friends L and S over for a Lunar New Year lunch. L is as good a cook as she is a baker, and her mother used to be a home economics teacher, so to say that she’s been exposed to good and honest home-cooking is an understatement. I decided on steamboat, which is suitably festive and takes the pressure off the cook, for all it really takes is one good broth.

I miss steamboat from Singapore dearly. Despite the reasonably large Chinese populations in Australia (where we previously lived for 5 years) and the Netherlands (where we currently live), the sort of steamboat that one typically finds is the tongue-numbing, fiery má là variety. That’s all fine, but it normally comes with so much MSG that it tastes more like it comes from a packet rather than being cooked from scratch, which is what I expect when I head out and spend money on a meal. Rare is the restaurant that makes you feel like a grandma is behind the stove, but that’s exactly how my favourite steamboat place in Singapore, Whampoa Keng, makes me feel. The broth is full-flavoured, as if the flavour has been coaxed out of bones for hours. What makes this style of broth distinctively Teochew is the addition of salted plums, that provide a subtle briny hit, and shards of deep-fried solefish.

Fish soup in Singapore

In Chaozhou, the birthplace of the Teochews, generous slices of fish are simmered in a simple and clear-tasting fish broth and served alongside rice. The clincher lies in the sheer freshness and natural sweetness of the fish. A milky variant of this dish became mainstream when the Cantonese in Singapore introduced the technique of deep-frying fish bones and boiling the stock vigorously for an intensely rich flavour and milky appearance. Operating within tight margins, hawkers soon learnt that one could simply add evaporated milk to clear fish broth to quickly achieve the same results. Less fish bones were required to produce a milky broth, and customers enjoyed the options of clear or milky fish soups without the fuss of the hawker having to prepare two separate broths.

Milky broth

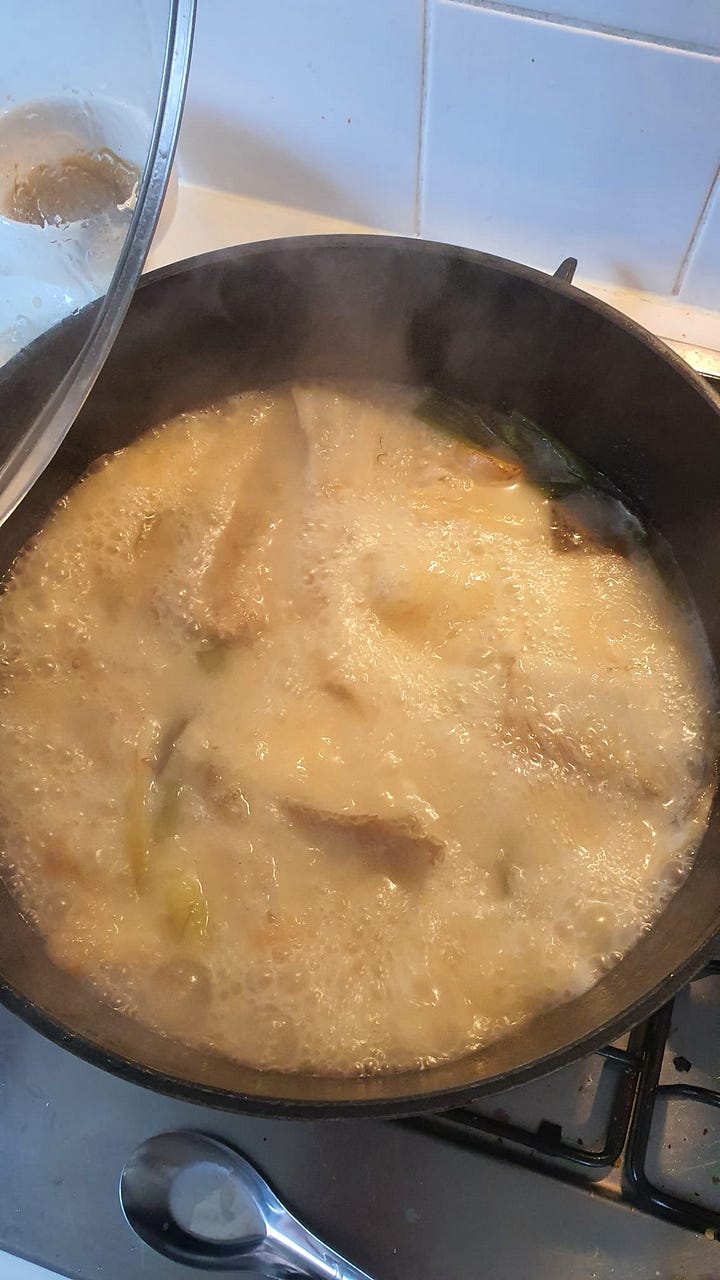

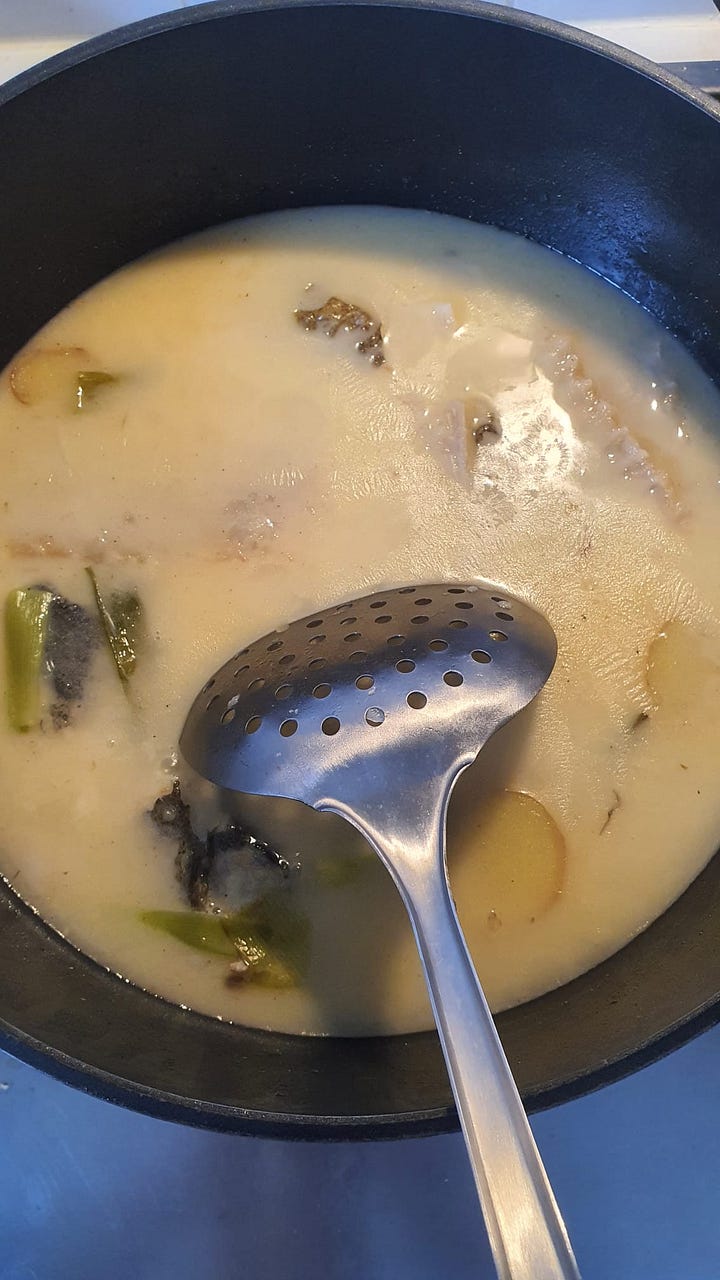

Despite the common practice of adding evaporated milk to fish broth in Singapore, there is no substitute for a naturally milky fish broth. It is nothing short of culinary magic to turn a fish stock from clear to creamy, and the closest comparison to something familiar is tonkotsu broth. Even though it is sometimes believed that a milky broth can only be achieved with pork bones, this is dispelled by ramen shops throughout Japan that serve tori paitan, a style of ramen with creamy-white chicken broth. The opacity of the broth is a result of the emulsification of fat and liquid, similar to when oil and liquid is energetically combined to make mayonnaise. Because fish is not as rich in fat deposits as pork or chicken, Cantonese cooks boost the fat content (and flavour) of the broth by deep-frying fish bones in oil. Pieces of fish are dredged in cornstarch and deep-fried until golden.

I also fry the fish pieces with spring onions and ginger, which is as classic a flavour combination in Chinese cooking as it gets. Especially when used in tandem with seafood, it has the benefit of suppressing any trace of fishiness. I then add homemade chicken stock to the bones, something that is not done in Chaozhou, where Teochew fish soup is only made with fish bones. When the Teochews moved to Singapore, however, it is said that they developed a liking for stronger flavours and began adding pork bones to bolster the flavour of the more delicate fish bones. Some hawkers use a trifecta of pork, fish, and chicken bones.

But fat and stock is only part of the equation. Once, seeing that we had a constant supply of chicken fat and chicken stock at Candlenut, I decided to make tori paitan for staffmeal one day. The approach was simple: combine them in a pot, reheat, and whiz everything together with a stick blender. The result thrilled me - in seconds, the broth was as bone-white as any tonkotsu broth from a ramen shop. However, barely 5 minutes later, the broth separated into two distinct layers.

The underrated MVP of tonkotsu-style broth is gelatin. When collagen in bones are simmered in water, they break down into gelatin. Being amphiphilic molecules, meaning that they attract fat on one end and water on the other, gelatin acts as a natural emulsifier. It is like the egg yolk in a mayonnaise. So the key, if you’re making a fish broth, is to use a fish that is rich in collagen. In Singapore, fish such as grouper or Spanish mackerel is used. I managed to get turbot head and frames from the fishmonger. In the event that you are unable to find fish that is collagen-rich, chicken feet, pork skin, or pig trotters can be added to the stock. Apart from acting as an emulsifier, gelatin also adds a lip-smacking quality that cannot be replicated by simply adding dairy.

Unlike a clear broth, any milky broth has to be rapidly boiled as the constant agitation helps with the emulsification process. It does not take long at all to achieve milky results, only 15 minutes. In any which case, cooking fish broth for too long is not advised as fish has delicate volatile aromatics that will boil off when cooked for too long. I keep the seasonings simple with ikan bilis powder (I can’t find solefish here in the Netherlands, sadly) and a couple of salted plums.

Nourishing, light yet rich, and surprisingly less effortful than you think. In terms of accompaniments, the sky is the limit, even though deep-fried taro, seaweed, and wombok are usually the must-haves for every Teochew steamboat feast. As a dip, a vinegary chilli sauce would be served, but the sky’s the limit! We had our steamboat with chilli chukka, a soy sauce chilli dip, and dried shrimp sambal because we’re Singaporeans and we can’t get enough of our condiments 😛

Milky Fish Broth

MAKES 4 SERVINGS