I never liked kueh salat as a child. This is a two-layered steamed dessert that comprises of pandan custard sitting atop lightly salted glutinous rice. Growing up in a family that did not make kueh, the commercialised specimens that I ate were always far too eggy, sweet, mushy and often a horrible garish green.

The first piece that changed my mind and the way I viewed the entire genre was from Candlenut. I had gone in for dinner and was served an elegant slice of kueh salat for dessert, alongside a quenelle of coconut sorbet. But unlike what I had been accustomed to eating, the custard was silky, smooth, and much lighter, not unlike a delicately set flan. The layer of glutinous rice beneath was also much thinner than that of traditional kueh salat, because according to Malcolm, the chef-owner, the custard is his favourite part. Rich but not at all heavy, it was a light but luxurious end to the meal.

That experience marked a turning point in my journey as a cook, for it showed me what it meant to respect traditions while modernising them sensibly. It also showed me that our food was artisanal; even something that I had thought of to be cheap and pedestrian, when made with care and attention, could be the highlight of a restaurant dinner. I sent my resume to Candlenut shortly after, and in my time working there, my biggest takeaway wasn’t any particular technique or skill, but a mindset. One of the things that Malcolm impressed upon me was the belief that our kueh could hold its own next to the other great desserts of the world. And why shouldn’t it? Achieving kueh salat perfection requires just as much patience, skill and technique as is required to nail the perfect honeycomb structure in your croissant.

Candlenut kickstarted a whole kueh salat revival in Singapore, and you can now find incredible versions made by home-based businesses in Singapore. For this reason, standards are set extraordinarily high, much higher than it ever was in Singapore. While it might seem daunting, I’m here to tell you that it *is* possible to make very good kueh salat at home. As with other forms of cooking or baking, once you understand the reasoning behind certain steps and techniques, the fog lifts and the path clears. And if you achieve anything less than perfection, at the end of the day, food is just food. The most important thing is the people whom you share it with. Now onto the deep-dive!

Because kueh salat is one of the most technical Singaporean desserts, I’ll be breaking it up into two parts:

Part I: General principles & my process of developing the recipe

Part II: A pictorial guide to making kueh salat, which includes the recipe and tips for success (for paid subscribers)

The rice

Two main communities prepare this kueh in Singapore - the Peranakans and the Malays. In the Malay version, the rice layer is kept white. On the other hand, the Peranakans stain the rice blue with blue pea flower. (Fun fact: according to Alan Goh of Travelling Foodies, because the colours blue, white and green are associated with funerals and mourning, one would never find this kueh being served at festive occasions.)

There are two ways to stain the rice blue. For an intense, vibrant effect, you can steep part of the rice overnight in the blue pea flower infusion, steam it separately from the white rice, and mix the two together. I much prefer the smudged out, subtler shade of blue that you get from drizzling blue pea flower-infused water over the glutinous rice.

Recipes differ in how long to soak the rice for, but I managed to get away with soaking the rice for an hour. Also, I steamed the drained rice with coconut milk, instead of splitting the steaming up into stages the way some recipes call for. Honestly, I cannot tell the difference in texture, so I’ll stick to the easiest way to do it. Regardless of which method you decide to go with, after the rice is cooked, it is compressed firmly with the back of a spoon or a press known as penekan kek lapis, which is customarily used in the making of kek lapis. Compacting the rice layer is important; failure to do so will lead to the custard flowing into and filling the gaps in the rice.

Custard technique

The custard is where things get tricky. Though the kueh is most commonly referred to as kueh salat (which makes reference to an old name for Singapore ‘selat’), its other names - kueh puteri salat (princess salat kueh) and kueh serimuka (pretty face kueh) - invoke the beauty and satiny smoothness of the custard layer. For that reason, bumps and pockmarks are unacceptable in good kueh salat.

The technique for making kueh salat is surprisingly rather European. Here are the steps:

Pandan juice, coconut milk, eggs, sugar and starch/flour, is combined.

The custard is cooked until thickened slightly. This achieves two things: a thickened custard is less lightly to penetrate the rice layer, and the starch or flour is less likely to separate when the custard is steamed.

The thickened custard is poured on top of the rice layer and steamed until set.

The method is remarkably similar to Heston Blumenthal’s recipe for lemon tart, where he heats the custard filling up in a double-boiler until it reaches 60°C, then strains it into a tart case and bakes it in the oven at a low temperature of 120°C.

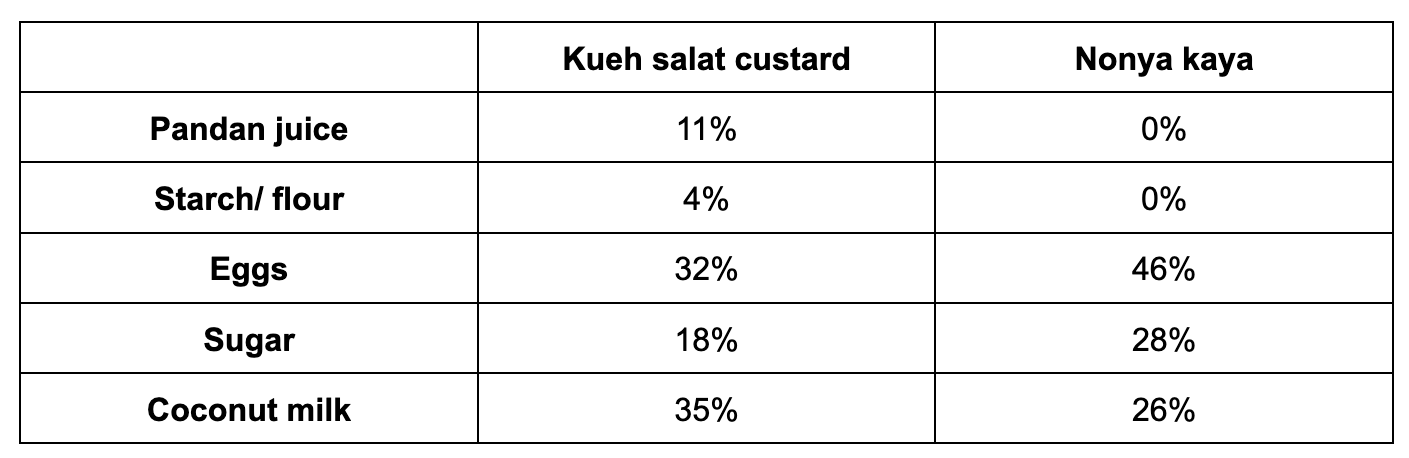

The same method is used when preparing Nonya kaya, unlike kaya prepared by other races, which is made on the stove-top from start to finish. It made me curious if kueh salat’s custard is fundamentally a Nonya kaya, so I did a quick comparison of both:

It turns out that Nonya kaya is far eggier and sweeter, which makes sense given that it is a thick jam to be spread on toast and kept for a longer period. Berwyn, a Peranakan cook who has truly earned his kueh salat stripes, tells me that because Nonya kaya has so much more eggs, the entire custard is able to set on its own when steamed, without need for starch or flour. But because kueh salat has a greater proportion of liquid, it benefits from “a modicum of flour” to help it set while still retaining a “flan-like texture”.

The impact of flour or starch

Alan Goh writes on his blog that while “every established cookbook on Straits Chinese cuisine written by the ‘doyens of Peranakan cooking’… incorporates flour of some sort in the batter”, “some older folks and traditionalists/purists claim that an ‘authentic’ kueh salat never uses flour to set the top pandan kaya layer.” But who is to say who’s wrong or right when there is such plurality in the way that we cook?

To test the impact that flour and starch has on kueh salat custard, I prepared four custards (without the pandan for ease):

Here are some tasting notes:

Control (no flour or starch): This was my least favourite. The texture on this was slightly brittle rather than fully creamy. It also reminded me of steamed egg in appearance with little air bubbles dotted throughout the mixture. Tasted especially eggy.

Cornstarch only: The texture was more kueh-like than the control as it felt more creamy than brittle, and reminded me of a pudding.

Flour only: This had the firmest set of the four, with the thickest mouthfeel and the most body.

Combination of cornstarch and flour: The custard was pretty close to the flour-only custard, but it was less squidgy while having a smooth and luscious mouthfeel.

So, even though purists beat their chests about not needing to rely on flour or starch to prepare kueh salat, the custard is better off with it in my opinion.

But in what proportion?

Proportion of flour and starch

I’ve seen a couple of videos where kueh salat is prepared with such a generous amount of flour and/or starch, that the end results look gummy or gel-like rather than creamy or custardy. Definitely not the results I was after! I prepared a trial batch with a minimal amount of flour and starch, but here’s where I encountered problems. The temperatures for egg protein coagulation and starch/ flour gelatinisation both begin at 62°C. However the window for full egg protein coagulation (62-70°C) is far narrower than that for starch/flour gelatinisation (62-95°C). Cornstarch and flour serve a function of stabilising eggs and preventing them from seizing up too quickly. Thus, when there is too little cornstarch and flour, the eggs might scramble before the starches have enough time to thicken.

I watched the custard like a hawk looking out for the creme anglaise consistency that multiple recipes call for, but by the time the mixture thickened sufficiently, the eggs had already scrambled and formed tiny lumps.

Steaming the custard carefully didn’t remedy the problem either, because by then it was a lost cause. The end result had a scrambled texture and was a little too soft owing to an insufficient quantity of starch/ flour:

I set out to increase the proportion of flour and starch in my recipe, but then I also had a thought: why not cook the cornstarch and flour separately?

I combined all the custard ingredients apart from the eggs in a pot and heated it until the mixture began to thicken. I took the temperature - it was 75°C. Had eggs been in this mixture, they probably would have begun to scramble. I whisked this mixture into the eggs, before straining to get rid of any stray egg strands.

At this point, my custard looked promising, with the viscosity of melted chocolate. It is essential to pour the custard gently over hot rice so that you don’t create any air bubbles - remember that what we’re looking for is a smooth surface. As you can see, the surface of my custard is smooth apart from one tiny bubble speck on the bottom, but hey - this is home-cooking! (Plus I’m not a Nonya cooking to seek the approval of a prospective mother-in-law 😛)

The kueh was steamed very gently until it was just set. It took 1 hour and 20 minutes in total. I took it out of the steamer, set it aside, and went to bed. The next day, I unmoulded and sliced it, and was thrilled with the end result. The TEXTURE was what I had hoped for. Silky smooth and slightly jiggly like a slab of tofu. It is all in the ratios I realise - a high water content keeps it light (just as chawanmushi is more delicate than straight up steamed egg because of the dashi that is added to it) and a low starch/ flour content sets it just so without a horrible gel-like texture.

You would also probably notice that I tweaked the ratio of rice to custard, as Wex, upon tasting the previous batch, requested for it to be 4:6 instead of 5:5. And I think it’s pretty perfect to me.

There are so many more tips and technicalities to dispense, so I’ll share them on part II of this deep dive in a separate email for paid subscribers! You’ll find my recipe and a pictorial guide that holds your hand throughout the kueh salat-making process, along with every single tip I’ve learnt along the way. If you’d like to read it and support the writing, research and recipe development that goes into this newsletter, please consider being a paid subscriber of Singapore Noodles:

For now I’m stoked to finally be that girl who brings kueh salat to a party! Thank you for following along! 🙋🏻♀️