Hello and welcome to Singapore Noodles, the newsletter with the mission of keeping Singaporean food heritage alive! Thank you for being here. If you are new and have not subscribed, you can do so to receive future recipes directly in your inbox:

Home fermentation has been all the rage these days and I’ve been in part very jealous of all the wonderful ferments out there on the internet, in part convinced that patience is not my strong suit. This delayed gratification is the only reason why I didn’t dabble much in sourdough during COVID, or why I don’t make my own salted duck eggs at home even though I really should. But, the kind folks at WRiceWine gifted me their glutinous rice wine and lees, which I’ve been actively cooking with and have now been used up. I’ve a grandmother-in-law who brews this wine on the regular, and everything that I need in my pantry - so I thought why not brew my own?

A little about glutinous rice wine - this is not something that is unique to the Chinese. There is tapuy or bayah in the Philippines (thank you Meryenda for telling me about this!), ruou nep cam in Vietnam, and sato in Thailand, just to name a few variations. In Singapore, rice wine-making is a vital tradition of two main communities - the Hakkas and the Foochows. The differences are not well-documented, and hybridisation of food traditions has made lines around food less concrete, but Hakka rice wine 黄酒/ 客家娘酒 tends to be yellow, while Foochow rice wine 红槽酒 is known for its deep red hue and distinctively full-bodied flavour.

For the Foochows, in particular, it is tradition to celebrate birthdays, weddings, and Chinese New Year with a bowl of mee sua cooked with red rice wine and lees (ang zao). Because the lees and wine are particularly nourishing, dishes made with these are a must-have for women in confinement. My in-laws aren’t Foochow or Hakka but, for some reason (might be simply a condition of living in Singapore where there’s so much diversity), they have incorporated wine-making into their own traditions. Wex and I got to eat ang zao mee sua on the day we got married!

If you’re wondering why I have wine biscuits and red yeast lees in my pantry, it is because this isn’t my first time fermenting wine. The first time I made it, I rushed the whole process (see what I mean by my impatience being my flaw) - the rice wasn’t soaked or cooked long enough, and so, didn’t break down properly during fermentation. This time I wanted to do it properly, and reached out to my mother-in-law, who sent me a very barebones recipe from her mum (Wex’s ahma) that became my starting point:

(She forgot to mention the red yeast rice, but specified 5 tbsp in a phonecall.)

Soaking the glutinous rice

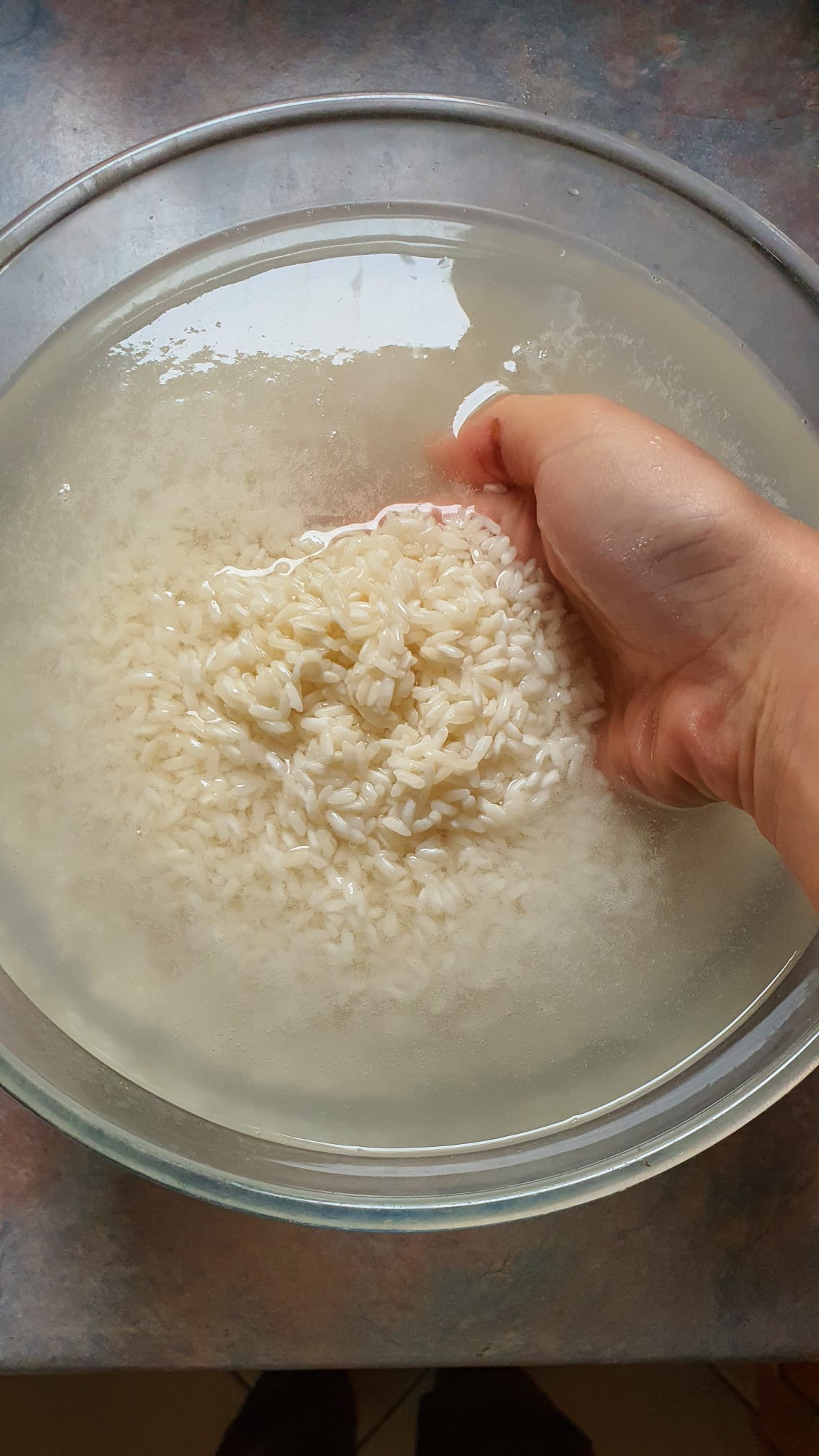

Many recipes online mention soaking the rice overnight. Ahma says 4 hours, but I think it’s mainly out of habit. When she cooks with glutinous rice for dumplings or png kueh, she tends to only soak the rice for 4 hours to avoid it becoming mushy. I figured since the point of fermenting glutinous rice is to turn it to liquid and the paste-like lees, soaking the rice longer would do some good. After an overnight’s soak, the rice was drained.

Steaming the rice

My mother-in-law had previously bought us a huge steamer, and it was perfect for this purpose. I lined it with a clean piece of cotton cloth and spread the rice out on it so that it was a not-too-thick, even layer. I steamed it for 30 minutes, by which point it was tender, but tasted a little dry. Worried that undercooked glutinous rice was going to ruin my wine again, I sprinkled over some water and steamed it further until it was pleasantly soft and tender.

One ingredient that Ahma’s recipe has that others don’t is rock sugar. It is probably to kickstart the process as this provides the yeast something to immediately feed on before the rice breaks down. I dissolved the sugar in boiling water while the rice cooked. While the rice steamed, I also disinfected a pot and jar with hot soapy water. When the rice was done, I transferred it into my scrupulously clean pot, and added the rock sugar mixture. Stirred it in thoroughly and waited for the rice to cool completely.

Warm rice is apparently the perfect breeding place for bacteria, so some people hasten the cooling by placing their rice in front of a fan or by spreading the rice out in a large tray. I live in Daylesford, which is exceptionally cold, and cooled the rice down in my widest pot. (I admit, the rice was a wee bit warm when I decided to proceed 🤪)

Adding the yeasts

To make this wine, two types of yeasts are ground to a powder (though some recipes call for red yeast rice to be left whole). The first are wine ‘biscuits’ (if you’re curious about how these are made, watch this very informative documentary.) There’s also red yeast rice, which lends the wine a deep, red colour. This ingredient is said to have medicinal properties and is commonly used as natural food colouring, such as in red fermented bean curd. If you live in Melbourne, you can find these ingredients at the Chinatown Asian grocer. In Singapore, you’ll be able to find them at the wet market.

Going through various recipes in cookbooks, there seems to be more ways than one to mix the yeasts with the rice:

Form the cooked rice into patties and dip the rice into the yeast powder to coat, before placing in the jar. (For a recipe using this method, check out Goz Lee’s Plusixfive cookbook.)

Layer the rice with the yeasts in a jar. (For a recipe using this method, check out Chinese Heritage Cooking by Christopher Tan and Amy Van.)

Mix it all up by hand. (Ahma’s method and the method that Mildred Voon outlines in Periuk.)

Following the way Ahma did it, I sprinkled my yeast powder all over the rice and began mixing. Cooled glutinous rice is not quite as supple as when it is warm, so Ah Ma recommends adding water. Boiled and cooled water, she stresses. How much? Enough so that when you lift up some of the rice mixture, it falls slowly from your spoon… about 3 seconds. Gotta love her descriptions! Apart from the quirkiness, it’s a wonderful testament of how the older generation do things by feel and sight, rather than rigid measurements.

Jarring for fermentation

Once the rice mixture is of the right consistency, I transferred it to my clean jar. It does not need to be tightly packed - air pockets are good! Traditional fermenting crocks are opaque to block out the light; I placed my jar in a dark cupboard to ferment. You can also place your jar in a garbage bag, which is what I eventually did when it was too cold to be left in the cupboard. For the first week or so of the fermentation, you don’t want the jar to be completely airtight as a lot of gas is produced at the start.

My mother-in-law’s instructions are to ferment this for 7 days, then give the mixture a stir and ferment airtight for another 14 days. I’ve also received messages from others who told me that they ferment their wine for 40-60 days. At the end of a total of 21 days, my wine was still not ready because this spring was horrendously cold. I’m going to trust the process and leave it for longer. You’ll find the recipe below, if you’d like to start fermenting your own wine! Will report back when mine is complete, and then we can look at ways to use the wine and lees in cooking 🧡✨

Red glutinous rice wine & lees

1kg glutinous rice + 300g tap water

150g rock sugar + 100g boiling water

40g (4 pieces) wine biscuits

30g red yeast rice

275g boiled and cooled water, or as needed

3 tbsp brandy

Rinse the glutinous rice and cover it with a liberal amount of water. Allow the rice to soak overnight (or at least 4 hours). Sterilize a large wide pot and jar by washing them with boiling soapy water and allow them to drip dry overnight.

The next day, drain the rice and place it on a large cloth-lined steamer (mine is 13-inch across). Spread it out to an even layer. If you don’t have a large steamer, you can place the rice in a dish for steaming instead, and steam the rice in batches. Drape the excess cloth over the rice, cover the steamer, and steam the rice for 30 minutes on high heat. Uncover the rice, drizzle in 300g water, stir it into the rice thoroughly. Steam for another 15 minutes on high heat, or until tender and soft.

While the rice steams, boil a kettle of water. Pour 100g boiling water over the rock sugar, stirring to help the rock sugar dissolve. Set the rock sugar mixture, and the rest of the boiled water, aside to cool.

When the rice is ready, transfer it to your clean pot. Pour in the rock sugar mixture while the rice is still warm, stirring it thoroughly. Allow the rice to cool completely. While the rice cools, blend the wine biscuits and red yeast rice to a powder, or use a pestle and mortar. Tip the powder into the rice and mix in the water gradually, combining everything with a large clean spoon. To test if there’s enough water, lift a spoonful of rice mixture and invert the spoon - if the mix falls back into the bowl after three seconds, that’s good.

Transfer the rice into a clean jar and cover the jar with a loosely fitted lid, making sure that there’s space between the rice and the cover. Place the jar in a cool dark spot, or cover with a garbage bag. Ferment for 7 days, then give the mixture a stir. Ferment for another 14 days or until you notice two layers - the wine lees (this is the result of the rice grains turning into a paste) and wine. Strain the contents of the jar into a sieve set over a pot and allow the wine to drip, without pressing to avoid cloudiness. Add the brandy to the wine, if desired, and transfer the wine to glass bottles.