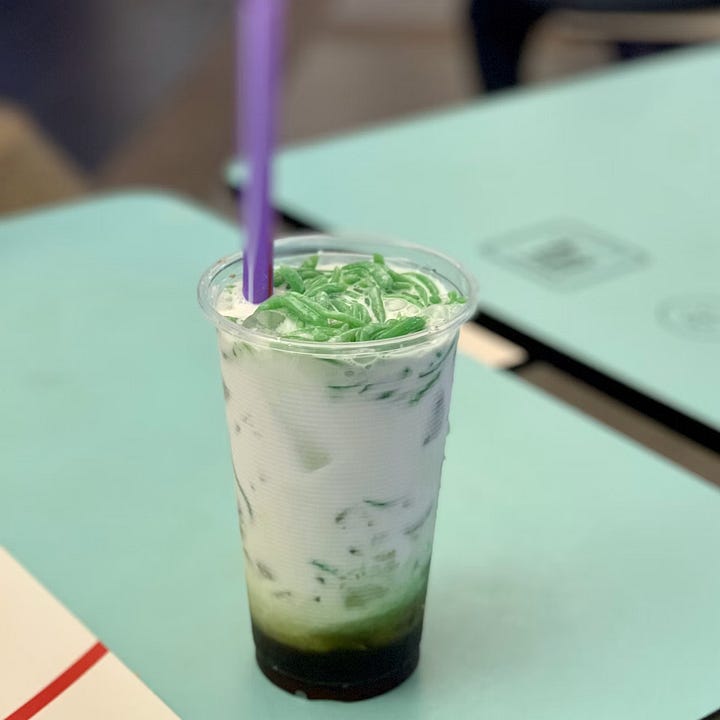

In Singapore, shaved ice desserts offer a much welcome dose of relief on the most bruising of summer days. It is believed that these were invented in the ports of British-ruled Malaya, when leftover ice used to refrigerate cargo in ships would be broken down and shaved into snow. One of the most iconic of these is chendol, a mini mountain of soft, powdery shaved ice drizzled with coconut milk and palm sugar syrup and topped with pandan noodles. There could be add-ons such as sweetened red beans, kidney beans, or sweet corn, but you can’t call the dessert a chendol without the green noodles, for they are what earn the dessert its namesake.

Earliest records of chendol date back to the 19th century in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and its name is said to be derived from the Indonesian word jendol, which means ‘swollen’ or ‘bulge’. Scholars theorise that chendol is a derivative of faloodeh, a Persian dish that has existed since 400 BC and was brought to Indonesia by Arab traders in the 12th and 13th centuries. (Faloodeh also made its way to India, where it is known as falooda.)

The common denominator between chendol and faloodeh is that they both contain jelly-like noodles that are made by pressing a hot starch batter through a sieve into ice water. The noodles in chendol have a more teardrop-like appearance while those in faloodeh, being pressed through a finer meshed sieve, resemble vermicelli.

Starch jellies and their variations in Asia

Starch jellies are nothing more than a starch and water mixture that is heated on the stove. As the slurry heats up, starch granules bind to water and swell. Eventually, they burst and release starch, thickening the surrounding liquid into a viscous and transparent slurry. When the slurry is chilled - either by allowing it to naturally cool, or adding it to chilled water - it sets into a gel.

Starch jellies have tremendous utility in the Asian kitchen, featuring in both cooling savoury and sweet dishes. In Chinese and Korean food cultures, mung bean starch jelly, known as cheongpo-muk 청포묵 and liáng fěn 凉粉, is often treated as a main savoury component in salads. In an interview from my vegetarian cookbook Plantasia, chef Sunny Lee describes her play on the meat and offal Sichuan salad ‘hushand and wife lung pieces’ 夫妻肺片, where mung bean starch jelly is combined with wood ear mushrooms and rehydrated daikon as a way to emulate the texture of cartilage, tendon, and meat.

In Japan, warabi mochi is little more than starch and water being cooked into a gel, allowed to set, and dusted with brown sugar and nutty toasted soy flour. Traditionally, starch ground from the root of the bracken fern is used, but lotus root starch or kudzu starch can also produce soft and chewy confections with slight variations in texture. Being just water and starch, mung bean jelly can operate as a blank canvas, but it can also be expressive once one swaps out the water for a flavoured liquid. In Taiwan, where years of Japanese rule has left an imprint on the culinary history of the island, street vendors sell warabi mochi flavoured and coloured with a variety of fruit juices. In Southeast Asia, chendol noodles are made with a combination of mung bean starch and pandan juice.

While chendol-making is rather straightforward, producing a good bowl of chendol is definitely an art. I had an incredible bowl of chendol on my last trip to Singapore at Thai Noodle House, where the noodles are made from scratch (a rarity these days) and they were inspiring to say the least. The noodles were intensely fragrant and grassy and walked a delicate tightrope of being tender but not mushy. With this as my benchmark, I experimented with the following: consistency of the mung bean batter when extruded, pH of the batter, and concentration of pandan juice.

Consistency

The process for extruding chendol is akin to that for spätzle, a type of pasta that is made by “grating” a flour-based batter through a slotted spoon into boiling water. In chendol, the temperatures are reversed: the hot batter of pandan juice and mung bean starch is extruded into chilled water to set it, forming noodles that set into tender, slippery ‘worms’.

A quick internet search pulled up images that ranged from beautiful teardrop jellies to more rustic, spätzle-like squiggles.