A kaya deep-dive

Making the pandan coconut jam

As the temperature dips, I’m craving warm, gooey, fragrant kaya. This is an egg ‘jam’ that is popular throughout Malaysia and Singapore and consists of four core ingredients - coconut milk, sugar, eggs and pandan. Like conventional fruit jam, it is enjoyed as a spread on toast, alongside generous lashings of salted butter.

The origin of this spread is contentious. Some say that it was a local adaptation of the Portuguese egg jam doce de ovos, which was introduced to the region by Portuguese colonists in the 16th century. Khir Johari, author of The Food of Singapore Malays, however, argues that the spread originates from Malay cuisine, from which the Portuguese took inspiration. Damian D’Silva, the chef at Rempapa who is widely regarded as the grandfather of heritage cuisine in Singapore, seems to be in agreement, explaining that ‘kaya’ means ‘rich’ in Malay, and coconut is a traditional Malay ingredient. The confection is also traditionally enjoyed in Peranakan households, given that Peranakan food has roots in Malay cuisine.

There are also those who attribute the invention of kaya to the Hainanese, who worked in European households and observed the making of Western fruit jams. To further substantiate, the explanation that ‘ka’ and ‘ya’ means ‘to stir’ and ‘coconut’ respectively in the Hainanese dialect is often given. Truthfully, I find the claim that kaya is a Hainanese invention to be unfounded - though the Hainanese, who only emigrated to Singapore after 1870, contributed greatly to the popularisation of this confection as a spread on toast, kaya was found “in different forms across Southeast Asia since at least the early 1600s”, as is stated in Christopher Tan’s The Way of Kueh.

Stovetop kaya

The most common method of making kaya is by stirring the egg and coconut mixture in a bain marie, cooking it slowly so that the eggs thicken without curdling. An added benefit of this gentle cooking over simmering water is that the mixture caramelises as it thickens, resulting in a rich and pronounced coconut flavour.

Pandan leaves can infuse their flavour into the spread in two ways - blended into juice to tint the kaya green, or knotted to nonetheless impart their lovely aroma. Even though Nonya kaya is often marketed as kaya of a green hue, multiple Peranakan friends tell me that traditional kaya is yellow, coloured only by the egg yolks. “But there are many who include pandan extract into their recipes. Or like me who likes a bit of gula Melaka,” says Berwyn Kwek, a Singaporean Peranakan based in Melbourne.

Cooked this way, a small batch of kaya (yielding one jar’s worth) takes approximately an hour to be ready.

Steamed kaya

There is also another traditional method to prepare kaya, where the coconut and egg mixture is steamed very gently until it sets to form a custard. Kwek refers to this as ‘kaya potong’ (‘cut kaya’), as the kaya is set so firmly that you could cut it into slices and enjoy it with bread. “It is definitely an endangered and lesser-known variety of kaya.”

Denise Fletcher, author of How to Cook Everything Singaporean, also makes her kaya by steaming. “I steam it as it's easier on the cook. I used to watch my grandmother stirring and stirring her kaya endlessly, roping in my mum, my aunt and even her older grandkids (myself included) if mum and aunt were busy. Steaming it means the cook can go about normal business as the kaya steams, instead of being chained to the stove.”

While some recipes for steamed kaya involve cooking the mixture on the stovetop until it thickens before steaming, Fletcher omits the pre-cooking in hers. “For me, a balance of taste, texture and convenience is what I aim for. We hardly have hours or strings of helpers to stir the kaya for 2 hours or even longer, nowadays.”

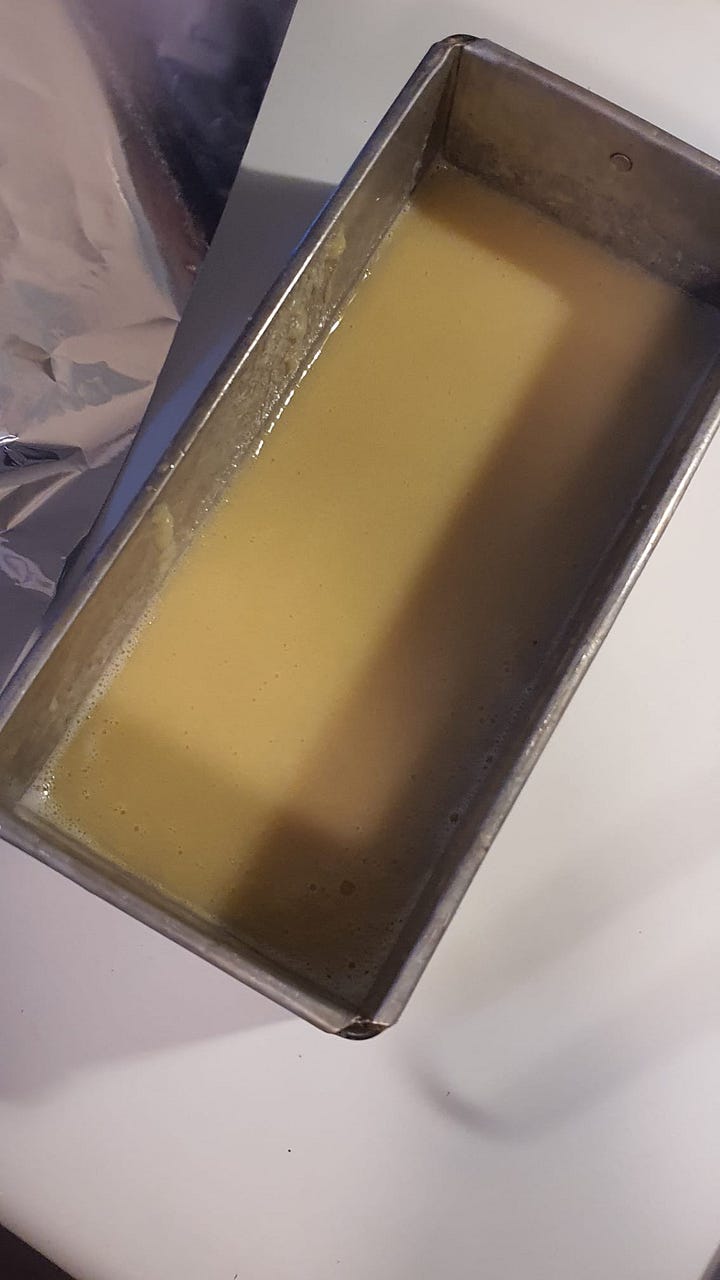

Taking Fletcher’s lead, I kept the stovetop cooking short - cooking the kaya just until the sugar dissolved before whisking it to the steamer. To create a wondrous shade of yellow in the custard, some cooks carefully select yolks from corn-fed chicken or kampung chicken, use a larger proportion of yolks. There are also recipes that call for gula melaka instead of white sugar for colour. As I intended to compare the flavour and texture of steamed kaya against the stovetop kaya, I chose to keep the recipe proportions and type of yolks and sugar used the same.

Hainanese kaya

I then made a third batch of kaya, also prepared using the traditional stirring method. This time, however, I mixed some caramelised sugar into the rest of the ingredients to make Hainanese kaya, known for its rich brown colour and lovely caramel fragrance. I made this kaya in an enamel bowl, which seemed to be a mistake. Given that the bowl was thin and conducted heat far more quickly than my glass bowl did, the mixture curdled and turned lumpy despite my diligent stirring. The conventional advice to remedy lumpy kaya is to blend it until smooth. I tried that with a small portion and while it was definitely smooth, it had a flowing consistency like rich cream, and was definitely not firm enough to spread on toast. Here’s the before and after:

I was close to throwing out the entire batch, but then I recalled Dinesh Rao’s lumpy kaya which he sells. I jarred all three batches and refrigerated them overnight for a taste-test.

Lumpy kaya - a mistake or a delight

I asked Fletcher what she thinks of lumpy kaya and she says, “It depends on who you ask. The older generation is notoriously finicky about texture and appearance and will likely deem lumpier kaya a fail.“ On the other hand, Kwek tells me, “I don’t ever recall eating a smooth one made by my grandma and other relatives. It was always textured.”

I came across the following two lumpy versions made by well-respected foodies in Singapore - Leslie Tay of ieatishootipost and Eddie Tan of Shiokman Eddie. In response to a commenter who asked if the kaya is meant to be lumpy, Tan replied that most Singaporeans are unaware that kaya made “in the olden days” were lumpy, and had “more texture and flavour compared to those watery smooth type”.

I set aside my prejudice against lumpy kaya and tasted all three kaya variants and here are my tasting notes (left to right):

Stovetop custard: Gooey, luscious, creamy and smooth. This was like eating decadent coconut and pandan-scented fudge. Shiny and translucent in appearance and oozes out of toast.

Steamed custard: More eggy compared to the other two and lacks the caramelised flavour of the stovetop custard. Lumpy but with no signs of graininess. Dense-textured and spreads thickly on toast.

Lumpy Hainanese custard, stovetop: Grainy; you can almost perceive the separation of water in the mouth. Caramel flavour distracted a little from the pure flavour of the coconut and pandan.

The traditional stovetop custard won hands down for me. Everyone has a different preference for kaya, and this oozy kaya is mine. While it *is* hard work to stir custard on the stove for an hour and there are tips and tricks to make kaya in 15 minutes, D’Silva’s words ring in my ears, “It’s not for every person. If you don't have patience, you shouldn't be doing kaya.”

To read about how to put your homemade kaya to use in a kaya toast set, click here 🧡

Stove-top kaya (yellow, green or brown variations)

Makes 1 jar